Hokkien

| Hokkien | |

|---|---|

| Min Nan, Quanzhang, Amoy | |

| |

| Región | China , Taiwán y el sudeste asiático |

| Etnicidad | Pueblo hokkien/hoklo |

Hablantes nativos | decenas de millones ( est. ) [a] [2] |

Formas tempranas | |

| Dialectos | |

| Estatus oficial | |

Idioma oficial en | Taiwán [c] |

| Regulado por | Ministerio de Educación de Taiwán |

| Códigos de idioma | |

| ISO 639-3 | nan(Min. del Sur) |

| Glotología | hokk1242 |

Distribución de las lenguas Min del Sur, con el hokkien en verde oscuro | |

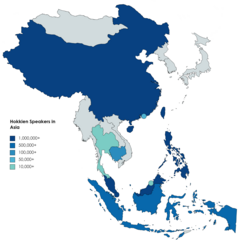

Políticas según el número de hablantes de hokkien ≥1.000.000 ≥500.000 ≥100.000 ≥50.000 Poblaciones minoritarias significativas | |

| Hokkien | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chino tradicional | 福建話 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chino simplificado | 福建话 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juez de primera instancia de Hokkien | Hok-kiàn-ōe / Hok-kiàn-ōa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Min del Sur / Min Nan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chino tradicional | 閩南話/閩南語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chino simplificado | 闽南话/闽南语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juez de primera instancia de Hokkien | Bân-lâm-ōe / Bân-lâm-ōa / Bân-lâm-gú / Bân-lâm-gí / Bân-lâm-gír | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hoklo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chino tradicional | 福佬話 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chino simplificado | 福佬话 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juez de primera instancia de Hokkien | Ho̍h-ló-ōe / Hô-ló-ōe / Hō-ló-ōe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lanlang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chino tradicional | 咱人話/咱儂話 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chino simplificado | 咱人话/咱侬话 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juez de primera instancia de Hokkien | Lán-lâng-ōe / Lán-nâng-ōe / Nán-nâng-ōe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

El hokkien ( chino : / ˈhɒk iɛn / HOK - ee-en; en inglés: / ˈh oʊk iɛn / HOH - kee - en ) [ 8] es una variedad de las lenguas min meridionales , nativa y originaria de la región de Minnan , en la parte sureste de Fujian , en el sureste de China continental . También se le conoce como Quanzhang ( chino:泉漳; pinyin: Quánzhāng ), a partir de los primeros caracteres de los centros urbanos de Quanzhou y Zhangzhou .

El hokkien taiwanés es una de las lenguas nacionales de Taiwán . El hokkien también se habla ampliamente en la diáspora china de ultramar en Singapur , Malasia , Filipinas , Indonesia , Camboya , Myanmar , Hong Kong , Tailandia , Brunei , Vietnam y otros lugares del mundo. La inteligibilidad mutua entre los dialectos del hokkien varía, pero aún se mantienen unidos por la identidad etnolingüística. [6]

En el sudeste asiático marítimo , el hokkien sirvió históricamente como lengua franca entre las comunidades chinas de ultramar de todos los dialectos y subgrupos , y sigue siendo hoy en día la variedad de chino más hablada en la región, incluso en Singapur , Malasia , Filipinas , Indonesia y Brunei . Esto se aplicó en menor medida al sudeste asiático continental . [9] Como resultado de la influencia significativa y la presencia histórica de su considerable diáspora en el extranjero, ciertas cantidades considerables a amplias de préstamos de hokkien también están históricamente presentes en los idiomas con los que ha tenido contacto histórico en su sprachraum , como el tailandés . El hokkien kelantan en el norte de Malaya de Malasia y el hokaglish hablado esporádicamente en Filipinas , especialmente en Metro Manila, también son idiomas mixtos con el hokkien como lexificador base . [ ¿Detalles excesivos? ]

Nombres

Los hablantes de hokkien en diferentes regiones se refieren al idioma como:

- Bân-lâm-gú / Bân-lâm-gí / Bân-lâm-gír / Bân-lâm-ú (闽南语;閩南語'lengua Min del Sur') en China, Taiwán, [10] y Malasia

- Bân-lâm-ōe / Bân-lâm-ōa / Bîn-lâm-ōe (闽南话;閩南話'discurso de Southern Min') en China, Taiwán, Filipinas y Malasia

- Tâi-gí / Tâi-gú (臺語'habla taiwanesa') o Ho̍h-ló-ōe / Hô-ló-ōe (福佬話'habla Hoklo') en Taiwán

- Lán-lâng-ōe / Lán-nâng-ōe / Nán-nâng-ōe (咱人話/咱儂話'el discurso de nuestro pueblo') en Filipinas

- Hok-kiàn-ōe / Hok-kiàn-ōa (福建話'lengua Hokkien') en Malasia, Singapur, Indonesia, Brunei y Filipinas

En algunas partes del sudeste asiático y en las comunidades de habla inglesa, el término hokkien ( [hɔk˥kiɛn˨˩] ) se deriva etimológicamente de la pronunciación hokkien de Fujian ( Hok-kiàn ), la provincia de la que proviene la lengua. En el sudeste asiático y en la prensa inglesa, hokkien se usa en el lenguaje común para referirse a los dialectos min meridionales del sur de Fujian, y no incluye referencias a dialectos de otras ramas siníticas también presentes en Fujian, como el idioma de Fuzhou ( min oriental ), el min pu-xian , el min septentrional , el chino gan o el hakka .

El término hokkien fue utilizado por primera vez por Walter Henry Medhurst en su Dictionary of the Hok-këèn Dialect of the Chinese Language, According to the Reading and Colloquial Idioms (Diccionario del dialecto hok-këèn de la lengua china, según la lectura y los modismos coloquiales) de 1832, considerado el primer diccionario hokkien basado en el inglés y la primera obra de referencia importante en POJ, aunque su sistema de romanización difiere significativamente del POJ moderno. En este diccionario, se utilizó la palabra hok-këèn . En 1869, POJ fue revisado nuevamente por John Macgowan en su libro publicado A Manual Of The Amoy Colloquial (Manual del coloquial de Amoy) . En este libro, këèn se cambió a kien como Hok-kien ; a partir de entonces, "hokkien" se usa con más frecuencia.

Históricamente, el hokkien también era conocido como " Amoy ", por la pronunciación hokkien de Zhangzhou de Xiamen ( Ēe-mûi ), el puerto principal en el sur de Fujian durante la dinastía Qing , como uno de los cinco puertos abiertos al comercio exterior por el Tratado de Nanking . [11] En 1873, Carstairs Douglas publicó el Diccionario chino-inglés de la lengua vernácula o hablada de Amoy, con las principales variaciones de los dialectos Chang-chew y Chin-chew , donde se hacía referencia al idioma como el "idioma de Amoy" [12] o como el "vernáculo de Amoy" [11] y en 1883, John Macgowan publicaría otro diccionario, el Diccionario inglés y chino del dialecto Amoy . [13] Debido a una posible confusión entre el idioma en su conjunto y su dialecto de Xiamen , muchos prohíben referirse al primero como "Amoy", un uso que se encuentra más comúnmente en los medios más antiguos y en algunas instituciones conservadoras.

En la clasificación utilizada por el Atlas de la Lengua de China , la rama Quanzhang del Min del Sur está formada por las variedades Min originarias de Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Xiamen y los condados orientales de Longyan ( Xinluo y Zhangping ). [14]

Distribución geográfica

El hokkien se habla en el barrio costero del sur de Fujian, el sureste de Zhejiang , así como en la parte oriental de Namoa en China; Taiwán; Metro Manila , Metro Cebú , Metro Davao y otras ciudades de Filipinas ; Singapur; Brunei; Medan , Riau y otras ciudades de Indonesia ; y en Perlis , Kedah , Penang y Klang en Malasia.

El hokkien se originó en la zona sur de la provincia de Fujian, un importante centro de comercio y migración, y desde entonces se ha convertido en una de las variedades chinas más comunes en el extranjero. El principal polo de variedades de hokkien fuera de Fujian es la cercana Taiwán, donde los inmigrantes de Fujian llegaron como trabajadores durante los 40 años de dominio holandés , huyendo de la dinastía Qing durante los 20 años de gobierno leal de Ming , como inmigrantes durante los 200 años de gobierno de la dinastía Qing , especialmente en los últimos 120 años después de que se relajaran las restricciones de inmigración, e incluso como inmigrantes durante el período de dominio japonés . El dialecto taiwanés tiene su origen principalmente en las variantes Tung'an, Quanzhou y Zhangzhou , pero desde entonces, el dialecto Amoy, también conocido como dialecto Xiamen, se ha convertido en el representante de prestigio moderno del idioma en China. Tanto Amoy como Xiamen provienen del nombre chino de la ciudad (厦门; Xiàmén ; Ē-mûi ); El primero proviene del idioma hokkien de Zhangzhou, mientras que el segundo proviene del mandarín.

Hay muchos hablantes de Min Nan entre las comunidades chinas de ultramar en el sudeste asiático, así como en los Estados Unidos ( hoklo estadounidenses ). Muchos emigrantes chinos étnicos Han a la región eran hoklo del sur de Fujian, y llevaron la lengua a lo que ahora es Myanmar, Vietnam , Indonesia (las antiguas Indias Orientales Holandesas ) y la actual Malasia y Singapur (anteriormente Malaya y los asentamientos británicos del estrecho ). La mayoría de los dialectos Min Nan de esta región han incorporado algunos préstamos extranjeros. Se dice que el hokkien es la lengua materna de hasta el 80% de la población étnica china en Filipinas, entre los que se conoce localmente como Lán-nâng-uē ("el habla de nuestro pueblo"). Los hablantes de hokkien forman el grupo más grande de chinos de ultramar en Singapur, Malasia, Indonesia y Filipinas. [ cita requerida ]

Clasificación

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

El sur de Fujian es el hogar de cuatro dialectos hokkien principales: Chiangchew , chinchew , tung'an y amoy , [15] originarios de las ciudades de Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, el histórico condado de Tung'an (同安縣, ahora Xiamen y Kinmen ) y el puerto de Amoy , respectivamente.

A finales del siglo XIX, el dialecto Amoy atrajo especial atención, porque Amoy era uno de los cinco puertos abiertos al comercio exterior por el Tratado de Nanking , pero antes de eso no había atraído la atención. [16] El dialecto Amoy se adopta como el 'Representante Moderno Min Nan'. El dialecto Amoy no puede interpretarse simplemente como una mezcla de los dialectos Zhangzhou y Quanzhou, sino que se forma sobre la base del dialecto Tung'an con aportes adicionales de otros subdialectos. [17] Ha desempeñado un papel influyente en la historia, especialmente en las relaciones de las naciones occidentales con China , y fue uno de los dialectos del hokkien más frecuentemente aprendidos por los occidentales durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX y principios del siglo XX.

La forma representativa moderna del hokkien que se habla en la ciudad taiwanesa de Tainan se parece mucho al dialecto tung'an. [18] [19] Todos los dialectos hokkien que se hablan en todo Taiwán se conocen colectivamente como hokkien taiwanés o holo localmente, aunque existe una tendencia a llamarlos idioma taiwanés por razones históricas. Lo hablan más taiwaneses que cualquier otra lengua sinítica, excepto el mandarín, y lo conoce la mayoría de la población; [20] por lo tanto, desde una perspectiva sociopolítica , forma un polo significativo de uso del idioma debido a la popularidad de los medios de comunicación en idioma holo. Douglas (1873/1899) también señaló que Formosa ( Taiwán ) ha sido poblada principalmente por emigrantes de Amoy (Xiamen), Chang-chew (Zhangzhou) y Chin-chew (Quanzhou). Por lo general, se encuentra que varias partes de la isla están habitadas especialmente por descendientes de dichos emigrantes, pero en Taiwán, las diversas formas de los dialectos mencionados anteriormente están bastante mezcladas. [21]

Sudeste asiático

Las variedades del hokkien en el sudeste asiático se originan a partir de estos dialectos. Douglas (1873) señala que

Singapur y los diversos asentamientos del Estrecho [como Penang y Malaca ] , Batavia [Yakarta] y otras partes de las posesiones holandesas [Indonesia] , están abarrotadas de emigrantes, especialmente de la prefectura de Chang-chew [Zhangzhou] ; Manila y otras partes de las Filipinas tienen grandes cantidades de emigrantes de Chin-chew [Quanzhou] , y los emigrantes están ampliamente dispersos de la misma manera en Siam [Tailandia] , Birmania [Myanmar] , la península malaya [Malasia peninsular] , Cochinchina [Vietnam del Sur, Camboya, Laos] , Saigón [ Ciudad Ho Chi Minh ] , etc. En muchos de estos lugares también hay una gran mezcla de emigrantes de Swatow [ Shantou ] . [21]

Sin embargo, en la actualidad, los chinos singapurenses , los chinos del sur de Malasia y los chinos indonesios de la provincia de Riau y las islas Riau hablan un dialecto mixto que desciende de los dialectos de Quanzhou , Amoy y Zhangzhou y que se acerca un poco más al dialecto de Quanzhou, posiblemente por ser del dialecto de Tung'an. Las variantes incluyen el hokkien de Malasia peninsular meridional y el hokkien de Singapur en Singapur.

Entre los chinos malayos de Penang y otros estados del norte de Malasia continental y los indonesios de etnia china de Medan y otras áreas del norte de Sumatra (Indonesia), se ha desarrollado una forma dialectal descendiente distinta del hokkien de Zhangzhou . En Penang , Kedah y Perlis , se lo denomina hokkien de Penang , mientras que al otro lado del estrecho de Malaca, en Medan , una variante casi idéntica se conoce como hokkien de Medan .

Muchos filipinos chinos profesan ascendencia de áreas de habla hokkien; el hokkien filipino también se deriva en gran medida del dialecto de Quanzhou, particularmente los dialectos de Jinjiang y Nan'an , con alguna influencia del dialecto de Amoy.

También hay hablantes de hokkien dispersos en otras partes de Indonesia (incluidas Yakarta y la isla de Java) , Tailandia, Myanmar , Malasia Oriental , Brunei, Camboya y Vietnam del Sur, aunque hay considerablemente más ascendencia teochew y swatow entre los descendientes de inmigrantes chinos en Malasia peninsular , Tailandia, Camboya, Laos y Vietnam del Sur.

Historia

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

Las variantes de los dialectos hokkien se pueden rastrear hasta 2-4 dialectos principales de origen: los dos originales son los dialectos de Quanzhou (泉州; Choân-chiu / Chôaⁿ-chiu ) y Zhangzhou (漳州; Chiang-chiu / Cheng-chiu ), y en siglos posteriores también Xiamen/Amoy (廈門; Ē-mn̂g / Ēe-mûi ) y Tong'an (同安; Tâng-oaⁿ ). Los dialectos Amoy y Tong'an son históricamente mezclas de los dialectos de Quanzhou y Zhangzhou , ya que son el punto medio geográfico y lingüístico entre los dos, mientras que el resto de los dialectos hokkien hablados en Taiwán y el sudeste asiático se derivan respectivamente de proporciones variables de los dialectos principales anteriores en el sur de Fujian.

Sur de Fujian

Durante el período de los Tres Reinos de la antigua China, hubo guerras constantes en las llanuras centrales de China. Los chinos étnicos Han migraron gradualmente desde Henan a la desembocadura del Yangtze a las costas de Zhejiang y más tarde comenzaron a ingresar a la región de Fujian , que en la antigüedad era originalmente el país Minyue , poblado por Baiyue no chinos , lo que provocó que la región por primera vez en la antigüedad incorporara dialectos chinos antiguos de los que más tarde se convertirían en chino Min . La migración masiva de chinos Han a la región de Fujian ocurrió principalmente después del Desastre de Yongjia . La corte Jìn huyó del norte al sur, lo que provocó que un gran número de chinos Han se mudaran a la región de Fujian. Trajeron el chino antiguo hablado en la llanura central de China desde la era prehistórica hasta el siglo III a Fujian, que más tarde se convirtió en Min, que luego se dividió en sus respectivas ramas, de las cuales el hokkien desciende de la rama Min del Sur .

En 677 (durante el reinado del emperador Gaozong de Tang ), Chen Zheng , junto con su hijo Chen Yuanguang , dirigió una expedición militar para reprimir una rebelión del pueblo She . En 885, (durante el reinado del emperador Xizong de Tang ), los dos hermanos Wang Chao y Wang Shenzhi , lideraron una fuerza de expedición militar para reprimir la rebelión de Huang Chao . [22] Las oleadas de migración desde el norte en esta era trajeron el idioma del chino medio a la región de Fujian, lo que dio al hokkien y a todas las demás lenguas Min sus lecturas literarias .

Xiamen

Durante el final del siglo XVII, cuando se levantaron las prohibiciones marítimas , el puerto de Xiamen , que eclipsaba al antiguo puerto de Yuegang , se convirtió en el principal puerto de Fujian, donde se legalizó el comercio. A partir de entonces, el dialecto de Xiamen, históricamente "Amoy", se convirtió en el principal dialecto hablado en el extranjero, como en Taiwán bajo el gobierno Qing , Malasia británica , los asentamientos del estrecho ( Singapur británico ), Hong Kong británico , Filipinas españolas (luego Filipinas americanas ), Indias Orientales Holandesas y Cochinchina francesa , etc. Históricamente, Xiamen siempre había sido parte del condado de Tung'an hasta después de 1912. [17] El dialecto Amoy fue la principal forma de prestigio del hokkien conocida desde finales del siglo XVII hasta la era republicana. Debido a esto, diccionarios, biblias y otros libros sobre hokkien de siglos recientes e incluso hasta el día de hoy en ciertos lugares, como escuelas e iglesias, de ciertos países, el idioma hokkien todavía se conoce como "Amoy".

Fuentes tempranas

Se conservan varios textos teatrales de finales del siglo XVI, escritos en una mezcla de dialectos de Quanzhou y Chaozhou. El más importante es el Romance del espejo de lichi , con manuscritos existentes que datan de 1566 y 1581. [23] [24]

A principios del siglo XVII, los frailes españoles en Filipinas produjeron materiales que documentaban las variedades del idioma hokkien habladas por la comunidad comercial china que se había establecido allí a fines del siglo XVI: [23] [25]

- Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china (1593), una versión Hokkien de la Doctrina Christiana . [26] [27] [28]

- Dictionarium Sino Hispanum (1604), de Pedro Chirino [29]

- Vocabulario de la Lengua Española y China / Vocabulario Hispánico y Chino [29]

- Bocabulario de la lengua sangleya por las letraz del ABC (1617), diccionario español-Hokkien, con definiciones. [29]

- Arte de la Lengua Chiõ Chiu (1620), una gramática español-Hokkien. [30]

- Diccionario Hispánico Sinicum (1626–1642), un diccionario principalmente español-hokkien (con una parte adicional incompleta en mandarín ), que proporciona palabras equivalentes, pero no definiciones. [31]

- Vocabulario de letra china (1643), de Francisco Díaz [29]

Estos textos parecen registrar un dialecto descendiente principalmente de Zhangzhou con algunas características atestiguadas de Quanzhou y Teo-Swa , del antiguo puerto de Yuegang (actual Haicheng , un antiguo puerto que ahora es parte de Longhai ). [32]

Fuentes del siglo XIX

Los eruditos chinos produjeron diccionarios de rimas que describen las variedades del idioma hokkien a principios del siglo XIX: [33]

- Lūi-im Biāu-ngō͘ (Huìyīn Miàowù) (彙音妙悟"Comprensión de los sonidos recopilados") fue escrito alrededor de 1800 por Huang Qian (黃謙) y describe el dialecto de Quanzhou. La edición más antigua que se conserva data de 1831.

- Lūi-chi̍p Ngé-sio̍k-thong Si̍p-ngó͘-im (Huìjí Yǎsútōng Shíwǔyīn) (彙集雅俗通十五音"Recopilación de los quince sonidos elegantes y vulgares") de Xie Xiulan (謝秀嵐) describe el dialecto de Zhangzhou. La edición más antigua que se conserva data de 1818.

El reverendo Walter Henry Medhurst basó su diccionario de 1832, "A Dictionary of the Hok-këèn Dialect of the Chinese Language" , en esta última obra. [34]

Otras obras populares del siglo XIX son también las del diccionario de 1883 del reverendo John Macgowan, " English and Chinese Dictionary of the Amoy Dialect" [13] y el diccionario de 1873 del reverendo Carstairs Douglas , "Chinese-English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy, with the Principal Variations of the Chang-Chew and Chin-Chew Dialects" [ 35] y su nueva edición de 1899 con el reverendo Thomas Barclay . [15]

Fonología

El hokkien tiene uno de los inventarios de fonemas más diversos entre las variedades chinas, con más consonantes que el mandarín estándar y el cantonés . Las vocales son más o menos similares a las del mandarín. Las variedades del hokkien conservan muchas pronunciaciones que ya no se encuentran en otras variedades chinas. Estas incluyen la retención de la /t/ inicial, que ahora es /tʂ/ (pinyin zh ) en mandarín (p. ej. , 竹; 'bambú' es tik , pero zhú en mandarín), habiendo desaparecido antes del siglo VI en otras variedades chinas. [36] Junto con otras lenguas min, que no descienden directamente del chino medio , el hokkien es de considerable interés para los lingüistas históricos para reconstruir el chino antiguo.

Initials

Hokkien has aspirated, unaspirated as well as voiced consonant initials. For example, the word 開; khui; 'open' and 關; kuiⁿ; 'close' have the same vowel but differ only by aspiration of the initial and nasality of the vowel. In addition, Hokkien has labial initial consonants such as m in 命; miā; 'life'.

Another example is 查埔囝; cha-po͘-kiáⁿ / ta-po͘-kiáⁿ / ta-po͘-káⁿ; 'boy' and 查某囝; cha-bó͘-kiáⁿ / cha̋u-kiáⁿ / cha̋u-káⁿ / chő͘-kiáⁿ; 'girl', which for the cha-po͘-kiáⁿ and cha-bó͘-kiáⁿ pronunciation differ only in the second syllable in consonant voicing and in tone.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | plain | p | t | k | ʔ | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced | b (m) | d[37]~l (n) | ɡ (ŋ) | |||

| (nasalized) | ||||||

| Affricate | plain | ts | ||||

| aspirated | tsʰ | |||||

| voiced | dz[38]~l~ɡ | |||||

| Fricative | s | h | ||||

| Semi-vowels | w | j | ||||

- All consonants but ʔ may be nasalized; voiced oral stops may be nasalized into voiced nasal stops.

- Nasal stops mostly occur word-initially.[39]

- Quanzhou and nearby may pronounce ⟨j⟩/⟨dz⟩ as ⟨l⟩ or ⟨g⟩.[citation needed]

- ⟨l⟩ is often interchanged with ⟨n⟩ and ⟨j⟩/⟨dz⟩ throughout different dialects.[40]

- ⟨j⟩, sometimes into ⟨dz⟩, is often pronounced very 'thick' so as to change to ⟨l⟩, or very nearly so.[21]

- Some dialects may pronounce ⟨l⟩ as ⟨d⟩, or a sound very like it.[37]

- Approximant sounds [w] [j], only occur word-medially, and are also realized as laryngealized [w̰] [j̰], within a few medial and terminal environments.[41]

Finals

Unlike Mandarin, Hokkien retains all the final consonants corresponding to those of Middle Chinese. While Mandarin only preserves the [n] and [ŋ] finals, Hokkien also preserves the [m], [p], [t] and [k] finals and has developed the glottal stop [ʔ].

The vowels of Hokkien are listed below:[42]

| Oral | Nasal | Stops | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | ∅ | e | i | o | u | ∅ | m | n | ŋ | i | u | p | t | k | ʔ | ||

| Nucleus | Vowel | a | a | ai | au | ã | ãm | ãn | ãŋ | ãĩ | ãũ | ap | at | ak | aʔ | ||

| i | i | io | iu | ĩ | ĩm | ĩn | ĩŋ | ĩũ | ip | it | ik | iʔ | |||||

| e | e | ẽ | ẽŋ* | ek* | eʔ | ||||||||||||

| ə | ə | ə̃m* | ə̃n* | ə̃ŋ* | əp* | ət* | ək* | əʔ* | |||||||||

| o | o | õŋ* | ot* | ok* | oʔ | ||||||||||||

| ɔ | ɔ | ɔ̃ | ɔ̃m* | ɔ̃n* | ɔ̃ŋ | ɔp* | ɔt* | ɔk | ɔʔ | ||||||||

| u | u | ue | ui | ũn | ũĩ | ut | uʔ | ||||||||||

| ɯ | ɯ* | ɯ̃ŋ* | |||||||||||||||

| Diphthongs | ia | ia | iau | ĩã | ĩãm | ĩãn | ĩãŋ | ĩãũ | iap | iat | iak | iaʔ | |||||

| iɔ | ĩɔ̃* | ĩɔ̃ŋ | iɔk | ||||||||||||||

| iə | iə | ĩə̃m* | ĩə̃n* | ĩə̃ŋ* | iəp* | iət* | |||||||||||

| ua | ua | uai | ũã | ũãn | ũãŋ* | ũãĩ | uat | uaʔ | |||||||||

| Others | ∅ | m̩ | ŋ̍ | ||||||||||||||

(*)Only certain dialects

- Oral vowel sounds are realized as nasal sounds when preceding a nasal consonant.

Dialectal sound shifts

The following table illustrates some of the more commonly seen sound shifts between various dialects. Pronunciations are provided in Pe̍h-ōe-jī and IPA.

| Character | Hokkien | Teochew | Haklau Min | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| operatic | Nan'an | Quanzhou | Xiamen | Zhangzhou | Zhangpu | Zhaoan | Chaozhou | Chaoyang | Haifeng | |

| 二 'two' | lī | lī | lī | lī | jī | jī | jī | jĭ | jĭ | jĭ |

| [li⁴¹] | [li³¹] | [li⁴¹] | [li²²] | [dʑi²²] | [dʑi²²] | [dʑi²²] | [dʑi³⁵] | [dʑi⁵³] | [dʑi³⁵] | |

| 坐 'to sit' | chěr | chěr | chěr | chē | chē | chē | chēr | chǒ | chǒ | chě |

| [tsə²²] | [tsə²²] | [tsə²²] | [tse²²] | [tse²²] | [tsɛ²²] | [tsə²²] | [tso³⁵] | [tso⁵³] | [tsɛ³⁵] | |

| 皮 'skin' | phêr | phêr | phêr | phê | phôe | phôe | phôe | phôe | phôe | phôe |

| [pʰə²⁴] | [pʰə²⁴] | [pʰə²⁴] | [pʰe²⁴] | [pʰuɛ¹³] | [pʰuɛ³¹²] | [pʰuɛ³⁵] | [pʰuɛ⁵⁵] | [pfʰuɛ³³] | [pʰuɛ⁵⁵] | |

| 雞 'chicken' | kire | koe | koe | koe | ke | kei | kei | koi | koi | kei |

| [kɯe³³] | [kue³³] | [kue³³] | [kue⁴⁴] | [ke³⁴] | [kiei⁴⁴] | [kei⁴⁴] | [koi³³] | [koi³¹] | [kei³³] | |

| 病 'sick' | pīⁿ | pīⁿ | pīⁿ | pīⁿ | pēⁿ | pēⁿ | pēⁿ | pēⁿ | pēⁿ | pēⁿ |

| [pĩ⁴¹] | [pĩ³¹] | [pĩ⁴¹] | [pĩ²²] | [pɛ̃²²] | [pɛ̃²²] | [pɛ̃²²] | [pɛ̃²¹] | [pɛ̃⁴²] | [pɛ̃³¹] | |

| 飯 'rice' | pn̄g | pn̄g | pn̄g | pn̄g | pūiⁿ | pūiⁿ | pūiⁿ | pūng | pn̄g | pūiⁿ |

| [pŋ̍⁴¹] | [pŋ̍³¹] | [pŋ̍⁴¹] | [pŋ̍²²] | [puĩ²²] | [puĩ²²] | [puĩ²²] | [puŋ²¹] | [pŋ̍⁴²] | [puĩ³¹] | |

| 自 'self' | chīr | chīr | chīr | chū | chū | chū | chīr | chīr | chū | chū |

| [tsɯ⁴¹] | [tsɯ³¹] | [tsɯ⁴¹] | [tsu²²] | [tsu²²] | [tsu²²] | [tsɯ²²] | [tsɯ²¹] | [tsu⁴²] | [tsu³¹] | |

| 豬 'pig' | tir | tir | tir | tu | ti | ti | tir | tir | tu | ti |

| [tɯ³³] | [tɯ³³] | [tɯ³³] | [tu⁴⁴] | [ti³⁴] | [ti⁴⁴] | [tɯ⁴⁴] | [tɯ³³] | [tu³¹] | [ti³³] | |

| 取 'to take' | chhú | chhú | chhú | chhú | chhí | chhí | chhír | chhú | chhú | chhí |

| [tsʰu⁵⁵] | [tsʰu⁵⁵] | [tsʰu⁵⁵] | [tsʰu⁵³] | [tɕʰi⁵³] | [tɕʰi⁵³] | [tsʰɯ⁵³] | [tsʰu⁵³] | [tsʰu⁴⁵] | [tɕʰi⁵³] | |

| 德 'virtue' | tirak | terk | tiak | tek | tek | tek | tek | tek | tek | tek |

| [tɯak⁵] | [tək⁵] | [tiak⁵] | [tiɪk³²] | [tiɪk³²] | [tɛk³²] | [tɛk³²] | [tɛk³²] | [tɛk⁴³] | [tɛk³²] | |

| 偶 'idol' | giró | gió | gió | ngó͘ | ngó͘ | ngóu | ngóu | ngóu | ngóu | ngóu |

| [ɡɯo⁵⁵] | [ɡio⁵⁵] | [ɡio⁵⁵] | [ŋɔ̃⁵³] | [ŋɔ̃⁵³] | [ŋɔ̃u⁵³] | [ŋɔ̃u⁵³] | [ŋou⁵³] | [ŋou⁴⁵] | [ŋou⁵³] | |

| 蝦 'prawn' | hê | hê | hê | hê | hê͘ | hê͘ | hê͘ | hê | hê | hê |

| [he²⁴] | [he²⁴] | [he²⁴] | [he²⁴] | [hɛ¹³] | [hɛ³¹²] | [hɛ³⁵] | [hɛ⁵⁵] | [hɛ³³] | [hɛ⁵⁵] | |

| 銀 'silver' | girêrn | gêrn | gûn | gûn | gîn | gîn | gîn | ngîrng | ngîng | ngîn |

| [ɡɯən²⁴] | [ɡən²⁴] | [ɡun²⁴] | [ɡun²⁴] | [ɡin¹³] | [ɡin³¹²] | [ɡin³⁵] | [ŋɯŋ⁵⁵] | [ŋiŋ³³] | [ŋin⁵⁵] | |

| 向 'to face' | hiòng | hiòng | hiòng | hiòng | hiàng | hiàng | hiàng | hiàng | hiàng | hiàng |

| [hiɔŋ⁴¹] | [hiɔŋ³¹] | [hiɔŋ⁴¹] | [hiɔŋ³¹] | [hiaŋ²¹] | [hiaŋ¹¹] | [hiaŋ¹¹] | [hiaŋ²¹²] | [hiaŋ⁵³] | [hiaŋ²¹²] | |

Tones

According to the traditional Chinese system, Hokkien dialects have 7 or 8 distinct tones, including two entering tones which end in plosive consonants. The entering tones can be analysed as allophones, giving 5 or 6 phonemic tones. In addition, many dialects have an additional phonemic tone ("tone 9" according to the traditional reckoning), used only in special or foreign loan words.[43] This means that Hokkien dialects have between 5 and 7 phonemic tones.

Tone sandhi is extensive.[44] There are minor variations between the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou tone systems. Taiwanese tones follow the patterns of Amoy or Quanzhou, depending on the area of Taiwan.

| Tones | level | rising | departing | entering | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dark level | light level | dark rising | light rising | dark departing | light departing | dark entering | light entering | ||

| Tone Number | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 8 | |

| Tone contour | Xiamen, Fujian | ˦˦ | ˨˦ | ˥˧ | – | ˨˩ | ˨˨ | ˧˨ | ˦ |

| 東 taŋ1 | 銅 taŋ5 | 董 taŋ2 | – | 凍 taŋ3 | 動 taŋ7 | 觸 tak4 | 逐tak8 | ||

| Taipei, Taiwan | ˦˦ | ˨˦ | ˥˧ | – | ˩˩ | ˧˧ | ˧˨ | ˦ | |

| – | |||||||||

| Tainan, Taiwan | ˦˦ | ˨˧ | ˦˩ | – | ˨˩ | ˧˧ | ˧˨ | ˦˦ | |

| – | |||||||||

| Zhangzhou, Fujian | ˧˦ | ˩˧ | ˥˧ | – | ˨˩ | ˨˨ | ˧˨ | ˩˨˩ | |

| – | |||||||||

| Quanzhou, Fujian | ˧˧ | ˨˦ | ˥˥ | ˨˨ | ˦˩ | ˥ | ˨˦ | ||

| – | |||||||||

| Penang, Malaysia[45] | ˧˧ | ˨˧ | ˦˦˥ | – | ˨˩ | ˧ | ˦ | ||

| – | |||||||||

Dialects

Hokkien is spoken in a variety of accents and dialects across the Minnan region. The Hokkien spoken in most areas of the three counties of southern Zhangzhou have merged the coda finals -n and -ng into -ng. The initial consonant j (dz and dʑ) is not present in most dialects of Hokkien spoken in Quanzhou, having been merged into the d or l initials.

The -ik or -ɪk final consonant that is preserved in the native Hokkien dialects of Zhangzhou and Xiamen is also preserved in the Nan'an dialect (色, 德, 竹) but are pronounced as -iak in Quanzhou Hokkien.[46]

- Hokkien

- Quanzhou Hokkien dialects (泉州腔; Choân-chiu khiuⁿ):

- Coastal Quanzhou Hokkien dialects (泉州海口腔; Choân-chiu Hái-kháu khiuⁿ)

- Coastal Nan'an dialect (海南安腔; Hái Lâm-oaⁿ khiuⁿ)

- Hui'an dialect (惠安腔; Hūi-oaⁿ khiuⁿ)

- Toubei dialect (in Quangang) (頭北話; Thâu-pak-ōe) (Transitionary with Pu-Xian Min)[clarification needed]

- Jinjiang dialect (晋江腔; Chìn-kang khiuⁿ)

- Luojiang dialect (洛江腔; Lo̍k-kang khiuⁿ)

- Quanzhou City Proper dialect (泉州市腔; Choân-chiu-chhǐ khiuⁿ)

- Philippine Hokkien (咱人話; Lán-nâng-ōe / Nán-nâng-ōe / Lán-lâng-ōe)

- Inland Quanzhou Hokkien dialects (泉州府城腔; Choân-chiu Hú-siâⁿ khiuⁿ)

- Anxi dialect (安溪腔; An-khoe khiuⁿ) (Transitionary with Zhangzhou dialect)

- Dehua dialect (德化腔; Tek-hòe khiuⁿ)

- Highland Nan'an dialect (頂南安腔; Téng Lâm-oaⁿ khiuⁿ)

- Yongchun dialect (永春腔; Éng-chhun khiuⁿ)

- Youxi dialect (尤溪腔; Iû-khe khiuⁿ) (Transitionary with Eastern Min and Central Min)[clarification needed]

- Datian Frontlect (大田前路話; Tōa-chhân Chûiⁿ-lō͘-ōe)* (Transitionary with Central Min)[clarification needed]

- Taoyuan dialect (大田桃源話; Tōa-chhân Thô-goân-ōe)* (Transitionary with Yong'an Central Min)[clarification needed]

- Coastal Quanzhou Hokkien dialects (泉州海口腔; Choân-chiu Hái-kháu khiuⁿ)

- Amoy-Tong'an Hokkien dialects (廈門同安腔; Ē-mn̂g Tâng-oaⁿ khiuⁿ) (Transitionary between Quanzhou dialects and Zhangzhou dialects)

- Amoy dialect (廈門腔; Ē-mn̂g khiuⁿ)

- Tong'an dialect (同安腔; Tâng-oaⁿ khiuⁿ) (Transitionary with Quanzhou dialect)

- Guankou dialect (灌口腔; Koàn-kháu khiuⁿ) (Transitionary with Zhangzhou dialect)

- Kinmen dialect (金門腔; Kim-mn̂g khiuⁿ)

- Southern Malacca Straits Hokkien

- Southern Peninsular Malaysian Hokkien (南馬福建話; Lâm-Má Hok-kiàn-oē)

- Singaporean Hokkien (新加坡福建話; Sin-ka-pho Hok-kiàn-ōe / Sin-ka-po Hok-kiàn-ōe)

- Riau Hokkien (in Riau Province, Riau islands, Jambi)

- Zhangzhou Hokkien dialects (漳州腔; Chiang-chiu khioⁿ):

- Northern Zhangzhou Hokkien dialects

- Changtai dialect (長泰腔; Tiôⁿ-thòa khioⁿ) (Transitionary with Quanzhou dialect)

- Haicang dialect (海滄腔; Hái-chhng khioⁿ) (Transitionary with Amoy dialect)

- Hua'an dialect (華安腔; Hôa-an khioⁿ) (Transitionary with Longyan dialect)

- Pinghe dialect (平和腔; Pêng-hô khioⁿ)

- Zhangzhou City Proper dialect (漳州市腔; Chiang-chiu-chhī khioⁿ)

- Longhai dialect (龍海腔; Liông-hái khioⁿ)

- Nanjing dialect (南靖腔; Lâm-chēng khioⁿ)

- Southern Zhangzhou Hokkien dialects

- Dongshan dialect (東山腔; Tang-soaⁿ khioⁿ)

- Yunxiao dialect (雲霄腔; Ûn-sio khioⁿ)

- Zhangpu dialect (漳浦腔; Chiuⁿ-phó͘ khioⁿ)

- Zhao'an dialect (詔安腔; Chiàu-an khioⁿ)* (Transitionary with Teo-Swa Min)

- Haklau Min / Hai Lok Hong / Hailufeng (海陸豐話; Hái-Lo̍k-hong-ōa)* (Transitionary with Teo-Swa Min and Hoiluk Hakka)[clarification needed]

- Haifeng dialect (海豐話; Hái-hong-ōa)*

- Lufeng dialect (陸豐話; Lo̍k-hong-ōa)*

- Northern Malacca Straits Hokkien

- Penang Hokkien (檳城福建話; Peng-siâⁿ Hok-kiàn-ōa / Pin-siâⁿ Hok-kiàn-ōa/庇能福建話; Pī-néeng Hok-kiàn-ōa)

- Medan Hokkien (棉蘭福建話; Mî-lân Hok-kiàn-oā)

- Northern Zhangzhou Hokkien dialects

- Longyan dialect (龍巖腔; Liông-nâ khioⁿ)* (Transitionary with Zhangping Hakka)[clarification needed]

- Taiwanese Hokkien (台語; Tâi-gí / Tâi-gú/臺灣話; Tâi-oân-ōe/臺灣閩南語; Tâi-oân Bân-lâm-gú / Tâi-oân Bân-lâm-gí)* (Transitionary between Zhangzhou dialects, Amoy-Tong'an dialects, and Quanzhou dialects)[clarification needed]

- Various dialects per region descended variously and mixed from the above as well (See Taiwanese Hokkien#Quanzhou–Zhangzhou inclinations)

- Quanzhou Hokkien dialects (泉州腔; Choân-chiu khiuⁿ):

*Haklau Min (Hai Lok Hong, including the Haifeng and Lufeng dialect), Chaw'an / Zhao'an (詔安話), Longyan Min, and controversially, Taiwanese, are sometimes considered as not Hokkien anymore, besides being under Southern Min (Min Nan). On the other hand, those under Longyan Min, Datian Min, Zhenan Min have some to little mutual intelligibility with Hokkien, while Teo-Swa Min, the Sanxiang dialect of Zhongshan Min, and Qiong-Lei Min also have historical linguistic roots with Hokkien, but are significantly divergent from it in terms of phonology and vocabulary, and thus have almost little to no practical face-to-face mutual intelligibility with Hokkien.[excessive detail?]

Comparison

The Xiamen dialect is a variant of the Tung'an dialect. Majority of Taiwanese, from Tainan, to Taichung, to Taipei, is also heavily based on Tung'an dialect while incorporating some vowels of Zhangzhou dialect, whereas Southern Peninsular Malaysian Hokkien, including Singaporean Hokkien, is based on the Tung'an dialect, with Philippine Hokkien on the Quanzhou dialect, and Penang Hokkien & Medan Hokkien on the Zhangzhou dialect. There are some variations in pronunciation and vocabulary between Quanzhou and Zhangzhou dialects. The grammar is generally the same.

Additionally, extensive contact with the Japanese language has left a legacy of Japanese loanwords in Taiwanese Hokkien. On the other hand, the variants spoken in Singapore and Malaysia have a substantial number of loanwords from Malay and to a lesser extent, from English and other Chinese varieties, such as the closely related Teochew and some Cantonese. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, there are also a few Spanish and Filipino (Tagalog) loanwords, while it is also currently a norm to frequently codeswitch with English, Tagalog, and in some cases other Philippine languages, such as Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Bicol Central, Ilocano, Chavacano, Waray-waray, Kapampangan, Pangasinense, Northern Sorsogonon, Southern Sorsogonon, etc.

Mutual intelligibility

Tong'an, Xiamen, Taiwanese, Singaporean dialects as a group are more mutually intelligible, but it is less so amongst the forementioned group, Quanzhou dialect, and Zhangzhou dialect.[47]

Although the Min Nan varieties of Teochew and Amoy are 84% phonetically similar including the pronunciations of un-used Chinese characters as well as same characters used for different meanings,[citation needed] and 34% lexically similar,[citation needed], Teochew has only 51% intelligibility with the Tong'an Hokkien|Tung'an dialect (Cheng 1997)[who?] whereas Mandarin and Amoy Min Nan are 62% phonetically similar[citation needed] and 15% lexically similar.[citation needed] In comparison, German and English are 60% lexically similar.[48]

Hainanese, which is sometimes considered Southern Min, has almost no mutual intelligibility with any form of Hokkien.[47]

Grammar

Hokkien is an analytic language; in a sentence, the arrangement of words is important to its meaning.[49] A basic sentence follows the subject–verb–object pattern (i.e. a subject is followed by a verb then by an object), though this order is often violated because Hokkien dialects are topic-prominent. Unlike synthetic languages, seldom do words indicate time, gender and plural by inflection. Instead, these concepts are expressed through adverbs, aspect markers, and grammatical particles, or are deduced from the context. Different particles are added to a sentence to further specify its status or intonation.

A verb itself indicates no grammatical tense. The time can be explicitly shown with time-indicating adverbs. Certain exceptions exist, however, according to the pragmatic interpretation of a verb's meaning. Additionally, an optional aspect particle can be appended to a verb to indicate the state of an action. Appending interrogative or exclamative particles to a sentence turns a statement into a question or shows the attitudes of the speaker.

Hokkien dialects preserve certain grammatical reflexes and patterns reminiscent of the broad stage of Archaic Chinese. This includes the serialization of verb phrases (direct linkage of verbs and verb phrases) and the infrequency of nominalization, both similar to Archaic Chinese grammar.[50]

汝

Lí

2SG

去

khì

go

買

bué

buy

有

ū

have

錶仔

pió-á

watch

無?

--bô?

no

汝 去 買 有 錶仔 無?

Lí khì bué ū pió-á --bô?

2SG go buy have watch no

"Did you go to buy a watch?"

As in many east Asian languages, classifiers are required when using numerals, demonstratives and similar quantifiers.

Choice of grammatical function words also varies significantly among the Hokkien dialects. For instance, (乞; knit) (denoting the causative, passive or dative) is retained in Jinjiang (also unique to the Jinjiang dialect is 度; thō͘ and in Jieyang, but not in Longxi and Xiamen, whose dialects use 互/予; hō͘ instead.[51]

Pronouns

Hokkien dialects differ in the pronunciation of some pronouns (such as the second person pronoun lí, lú, or lír), and also differ in how to form plural pronouns (such as n or lâng). Personal pronouns found in the Hokkien dialects are listed below:

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 我 góa | 阮1 gún, góan 咱2 or 俺 lán or án 我儂1,3 góa-lâng |

| 2nd person | 汝 lí, lír, lú | 恁 lín 汝儂3 lí-lâng, lú-lâng |

| 3rd person | 伊 i | 𪜶 in 伊儂3 i-lâng |

- 1 Exclusive

- 2 Inclusive

- 3 儂; lâng is typically suffixed in Southeast Asian Hokkien dialects (with the exception of Philippine Hokkien)

Possessive pronouns can be marked by the particle 的; ê), in the same way as normal nouns. In some dialects, possessive pronouns can also be formed with a nasal suffix, which means that possessive pronouns and plural pronouns are homophones:[52]

The most common reflexive pronoun is ka-kī (家己). In formal contexts, chū-kí (自己) is also used.

Hokkien dialects use a variety of demonstrative pronouns, which include:

- 'this' – che (這,即),chit-ê (即個)

- 'that' – he (許,彼),hit-ê (彼個)

- 'here' – hia (遮),chit-tau (即兜)

- 'there' – hia (遐),hit-tau (彼兜)

The interrogative pronouns include:

- 'what' – siáⁿ-mih (啥物),sím-mih (甚麼),há-mi̍h (何物)

- 'when' – tī-sî (底時),kúi-sî (幾時),tang-sî (當時),sím-mih sî-chūn (甚麼時陣)

- 'where' – tó-lo̍h (倒落),tó-uī (倒位)

- 'who' – siáⁿ-lâng (啥人),siáng (誰),

- 'why' – ūi-siáⁿ-mih (為啥物),ūi-sím-mih (為甚物),án-chóaⁿ (按怎),khah (盍)

- 'how' – án-chóaⁿ (按怎),lû-hô (如何),cháiⁿ-iūⁿ (怎樣)

Copula

States and qualities are generally expressed using stative verbs that do not require a verb meaning 'to be':

我

goá

1SG

腹肚

pak-tó͘

stomach

枵。

iau.

hungry

我 腹肚 枵。

goá pak-tó͘ iau.

1SG stomach hungry

"I am hungry."

With noun complements, the verb sī (是) serves as the verb 'to be'.

昨昏

cha-hng

是

sī

八月節。

poeh-ge̍h-choeh.

昨昏 是 八月節。

cha-hng sī poeh-ge̍h-choeh.

"Yesterday was the Mid-Autumn festival."

To indicate location, the words tī (佇) tiàm (踮), leh (咧), which are collectively known as the locatives or sometimes coverbs in Chinese linguistics, are used to express '(to be) at':

我

goá

踮

tiàm

遮

chia

等

tán

汝。

lí.

我 踮 遮 等 汝。

goá tiàm chia tán lí.

"I am here waiting for you."

伊

i

這摆

chit-mái

佇

tī

厝

chhù

裡

lāi

咧

leh

睏。

khùn.

伊 這摆 佇 厝 裡 咧 睏。

i chit-mái tī chhù lāi leh khùn.

"They're sleeping at home now."

Negation

Hokkien dialects have a variety of negation particles that are prefixed or affixed to the verbs they modify. There are six primary negation particles in Hokkien dialects (with some variation in how they are written in characters):[excessive detail?]

Other negative particles include:

- bâng (甭)

- bián (免)

- thài (汰)

The particle m̄ (毋,呣,唔,伓) is general and can negate almost any verb:

伊

i

3SG

毋

m̄

not

捌

bat

know

字。

jī

character

伊 毋 捌 字。

i m̄ bat jī

3SG not know character

"They cannot read."

The particle mài (莫,【勿爱】), a concatenation of m-ài (毋愛) is used to negate imperative commands:

莫

mài

講!

kóng

莫 講!

mài kóng

"Don't speak!"

The particle bô (無) indicates the past tense:[dubious – discuss]

伊

i

無

bô

食。

chia̍h

伊 無 食。

i bô chia̍h

"They did not eat."

The verb 'to have', ū (有) is replaced by bô (無) when negated (not 無有):

伊

i

無

bô

錢。

chîⁿ

伊 無 錢。

i bô chîⁿ

"They do not have any money."

The particle put (不) is used infrequently, mostly found in literary compounds and phrases:

伊

i

真

chin

不孝。

put-hàu

伊 真 不孝。

i chin put-hàu

They are really unfilial."

Vocabulary

The majority of Hokkien vocabulary is monosyllabic.[53][better source needed] Many Hokkien words have cognates in other Chinese varieties. That said, there are also many indigenous words that are unique to Hokkien and are potentially not of Sino-Tibetan origin, while others are shared by all the Min dialects (e.g. 'congee' is 糜 mê, bôe, bê, not 粥 zhōu, as in other dialects).

As compared to Mandarin, Hokkien dialects prefer to use the monosyllabic form of words, without suffixes. For instance, the Mandarin noun suffix 子; zi is not found in Hokkien words, while another noun suffix, 仔; á is used in many nouns. Examples are below:

- 'duck' – 鴨; ah or 鴨仔; ah-á (cf. Mandarin 鴨子; yāzi)

- 'color' – 色; sek (cf. Mandarin 顏色; yán sè)

In other bisyllabic words, the syllables are inverted, as compared to Mandarin. Examples include the following:

- 'guest' – 人客; lâng-kheh (cf. Mandarin 客人; kèrén)

In other cases, the same word can have different meanings in Hokkien and Mandarin. Similarly, depending on the region Hokkien is spoken in, loanwords from local languages (Malay, Tagalog, Burmese, among others), as well as other Chinese dialects (such as Southern Chinese dialects like Cantonese and Teochew), are commonly integrated into the vocabulary of Hokkien dialects.

Literary and colloquial readings

The existence of literary and colloquial readings is a prominent feature of some Hokkien dialects and indeed in many Sinitic varieties in the south. The bulk of literary readings (文讀; bûn-tha̍k), based on pronunciations of the vernacular during the Tang dynasty, are mainly used in formal phrases and written language (e.g. philosophical concepts, given names, and some place names), while the colloquial (or vernacular) ones (白讀; pe̍h-tha̍k) are usually used in spoken language, vulgar phrases and surnames. Literary readings are more similar to the pronunciations of the Tang standard of Middle Chinese than their colloquial equivalents.

The pronounced divergence between literary and colloquial pronunciations found in Hokkien dialects is attributed to the presence of several strata in the Min lexicon. The earliest, colloquial stratum is traced to the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE); the second colloquial one comes from the period of the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589 CE); the third stratum of pronunciations (typically literary ones) comes from the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) and is based on the prestige dialect of Chang'an (modern day Xi'an), its capital.[54]

Some commonly seen sound correspondences (colloquial → literary) are as follows:

- p- ([p-], [pʰ-]) → h ([h-])

- ch-, chh- ([ts-], [tsʰ-], [tɕ-], [tɕʰ-]) → s ([s-], [ɕ-])

- k-, kh- ([k-], [kʰ-]) → ch ([tɕ-], [tɕʰ-])

- -ⁿ ([-ã], [-uã]) → n ([-an])

- -h ([-ʔ]) → t ([-t])

- i ([-i]) → e ([-e])

- e ([-e]) → a ([-a])

- ia ([-ia]) → i ([-i])

This table displays some widely used characters in Hokkien that have both literary and colloquial readings:[55][56]

| Chinese character | Reading pronunciations | Spoken pronunciations / †explications | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| 白 | pe̍k | pe̍h | white |

| 面 | biān | bīn | face |

| 書 | su | chu | book |

| 生 | seng | seⁿ / siⁿ | student |

| 不 | put | m̄† | not |

| 返 | hóan | tńg† | return |

| 學 | ha̍k | o̍h | to study |

| 人 | jîn / lîn | lâng† | person |

| 少 | siàu | chió | few |

| 轉 | chóan | tńg | to turn |

This feature extends to Hokkien numerals, which have both literary and colloquial readings.[56] Literary readings are typically used when the numerals are read out loud (e.g. phone numbers, years), while colloquial readings are used for counting items.

| Numeral | Reading | Numeral | Reading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literary | Colloquial | Literary | Colloquial | ||

| 1 | it | chi̍t | 6 | lio̍k | la̍k |

| 2 | jī, lī | nn̄g | 7 | chhit | |

| 3 | sam | saⁿ | 8 | pat | peh, poeh |

| 4 | sù, sìr | sì | 9 | kiú | káu |

| 5 | ngó͘ | gō͘ | 10 | si̍p | cha̍p |

Semantic differences between Hokkien and Mandarin

Quite a few words from the variety of Old Chinese spoken in the state of Wu, where the ancestral language of Min and Wu dialect families originated, and later words from Middle Chinese as well, have retained the original meanings in Hokkien, while many of their counterparts in Mandarin Chinese have either fallen out of daily use, have been substituted with other words (some of which are borrowed from other languages while others are new developments), or have developed newer meanings. The same may be said of Hokkien as well, since some lexical meaning evolved in step with Mandarin while others are wholly innovative developments.

This table shows some Hokkien dialect words from Classical Chinese, as contrasted to the written Mandarin:

| Gloss | Hokkien | Mandarin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanji | POJ | Hanzi | Pinyin | |

| 'eye' | 目睭/目珠 | ba̍k-chiu | 眼睛 | yǎnjīng |

| 'chopstick' | 箸 | tī, tīr, tū | 筷子 | kuàizi |

| 'to chase' | 逐 | jiok, lip | 追 | zhuī |

| 'wet' | 澹[57] | tâm | 濕 | shī |

| 'black' | 烏 | o͘ | 黑 | hēi |

| 'book' | 冊 | chheh | 書 | shū |

For other words, the classical Chinese meanings of certain words, which are retained in Hokkien dialects, have evolved or deviated significantly in other Chinese dialects. The following table shows some words that are both used in both Hokkien dialects and Mandarin Chinese, while the meanings in Mandarin Chinese have been modified:

| Word | Hokkien | Mandarin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POJ | Gloss (and Classical Chinese) | Pinyin | Gloss | |

| 走 | cháu | 'to flee' | zǒu | 'to walk' |

| 細 | sè, sòe | 'tiny', 'small, 'young' | xì | 'thin', 'slender' |

| 鼎 | tiáⁿ | 'pot' | dǐng | 'tripod' |

| 食 | chia̍h | 'to eat' | shí | 'to eat' (largely superseded by 吃) |

| 懸 | kôan, koâiⁿ, kûiⁿ | 'tall', 'high' | xuán | 'to hang', 'to suspend' |

| 喙 | chhùi | 'mouth' | huì | 'beak' |

Words from Min Yue

Some commonly used words, shared by all[citation needed][dubious – discuss] Min Chinese languages, came from the Old Yue languages. Jerry Norman suggested that these languages were Austroasiatic. Some terms are thought be cognates with words in Tai Kadai and Austronesian languages. They include the following examples, compared to the Fuzhou dialect, a Min Dong language:

| Word | Hokkien POJ | Foochow Romanized | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| 骹 | kha [kʰa˥] | kă [kʰa˥] | 'foot and leg' |

| 囝 | kiáⁿ [kjã˥˩] | giāng [kjaŋ˧] | 'son', 'child', 'whelp', 'a small amount' |

| 睏 | khùn [kʰun˨˩] | káung [kʰɑwŋ˨˩˧] | to sleep |

| 骿 | phiaⁿ [pʰjã˥] | piăng [pʰjaŋ˥] | 'back', 'dorsum' |

| 厝 | chhù [tsʰu˨˩] | chuó, chió [tsʰwɔ˥˧] | 'home', 'house' |

| 刣 | thâi [tʰaj˨˦] | tài [tʰaj˥˧] | 'to kill', 'to slaughter' |

| (肉) | bah [baʔ˧˨] | — | 'meat' |

| 媠 | suí [sui˥˧] | — | 'beautiful' |

| 檨 | soāiⁿ [suãi˨˨] | suông [suɔŋ˨˦˨] | 'mango' (Austroasiatic)[58][59] |

Loanwords

Loanwords are not unusual among Hokkien dialects, as speakers readily adopted indigenous terms of the languages they came in contact with. As a result, there is a plethora of loanwords that are not mutually comprehensible among Hokkien dialects.

Taiwanese Hokkien, as a result of linguistic contact with Japanese[60] and Formosan languages, contains many loanwords from these languages. Many words have also been formed as calques from Mandarin, and speakers will often directly use Mandarin vocabulary through codeswitching. Among these include the following examples:

- 'toilet' – piān-só͘ (便所) from Japanese benjo (便所)

- Other Hokkien variants: 屎礐 (sái-ha̍k), 廁所 (chhek-só͘)

- 'car' – chū-tōng-chhia (自動車) from Japanese jidōsha (自動車)

- Other Hokkien variants: 風車 (hong-chhia), 汽車 (khì-chhia)

- 'to admire' – kám-sim (感心) from Japanese kanshin (感心)

- Other Hokkien variants: 感動 (kám-tōng)

- 'fruit' – chúi-ké / chúi-kóe / chúi-kér (水果) from Mandarin (水果; shuǐguǒ)

- Other Hokkien variants: 果子 (ké-chí / kóe-chí / kér-chí)

Singaporean Hokkien, Penang Hokkien and other Malaysian Hokkien dialects tend to draw loanwords from Malay, English as well as other Chinese dialects, primarily Teochew. Examples include:

- 'but' – ta-pi, from Malay

- Other Hokkien variants: 但是 (tān-sī)

- 'doctor' – 老君; ló-kun, from Malay dukun

- Other Hokkien variants: 醫生 (i-seng)

- 'stone', 'rock' – bà-tû, from Malay batu

- Other Hokkien variants: 石頭 (chio̍h-thâu)

- 'market' – 巴剎 pa-sat, from Malay pasar from Persian bazaar (بازار)[61]

- Other Hokkien variants: 市場 (chhī-tiûⁿ), 菜市 (chhài-chhī)

- 'they' – 伊儂 i-lâng from Teochew (i1 nang5)

- Other Hokkien variants: c𪜶 (in)

- 'together' – 做瓠 chò-bú from Teochew 做瓠 (jo3 bu5)

- Other Hokkien variants: 做夥 (chò-hóe), 同齊 (tâng-chê) or 鬥陣 (tàu-tīn)

- 'soap' – 雪文 sap-bûn from Malay sabun, from Arabic ṣābūn (صابون).[61][62]

Philippine Hokkien, as a result of centuries-old contact with both Philippine languages and Spanish and due to recent 20th century modern contact with English, also incorporate words from these languages. Speakers today will also often directly use English and Filipino (Tagalog), or other Philippine languages like Bisaya, vocabulary through codeswitching. Examples of loans considered by native speakers to be part of the language already include:

- 'cup' – ba-sù, from either Tagalog baso or Spanish vaso

- Other Hokkien variants: 杯仔; poe-á, 杯; poe

- 'office' – o-pi-sín, from Tagalog opisina, which itself is from Spanish oficina

- Other Hokkien variants: 辦公室; pān-kong-sek/pān-kong-siak

- 'soap' – sap-bûn, from either Tagalog sabon or Early Modern Spanish xabon

- 'coffee' – ka-pé, from Tagalog kape, which itself is from Spanish café

- Other Hokkien variants: 咖啡; ko-pi, 咖啡; ka-pi

- 'to pay' – pá-lâ, from Spanish pagar

- Other Hokkien variants: 予錢; hō͘-chîⁿ, 還錢; hêng-chîⁿ

- 'dozen' – lo-sin, from English dozen

- Other Hokkien variants: 打; táⁿ

- 'jeepney' – 集尼車; chi̍p-nî-chhia, from Philippine English jeepney

- 'rubber shoes' (sneakers) – go-ma-ôe, calqued from Philippine English rubber shoes ("sneakers"), using Tagalog goma ("rubber") or Spanish goma ("rubber") + Hokkien 鞋 (ôe, "shoe")

Philippine Hokkien usually follows the 3 decimal place Hindu-Arabic numeral system used worldwide, but still retains the concept of 萬; bān; 'ten thousand' from the Chinese numeral system, so 'ten thousand' would be 一萬; chi̍t-bān, but examples of the 3 decimal place logic have produced words like:

- 'eleven thousand' – 十一千; cha̍p-it-chheng, and same idea for succeeding numbers

- Other Hokkien variants: 一萬一千; chi̍t-bān chi̍t-chheng

- 'one hundred thousand' – 一百千; chi̍t-pah-chheng, and same idea for succeeding numbers

- Other Hokkien variants: 十萬; cha̍p-bān

- 'one million' – 一桶; chi̍t-tháng or 一面桶; chi̍t-bīn-tháng, and same idea for succeeding numbers

- Other Hokkien variants: 一百萬; chi̍t-pah-bān

- 'one hundred million' – 一百桶; chi̍t-pah-tháng, and same idea for succeeding numbers

- Other Hokkien variants: 一億; chi̍t-iak

Comparison with Mandarin and Sino-Xenic pronunciations

| Gloss | Characters | Mandarin | Yue | Hokkien[63] | Korean | Vietnamese | Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 'book' | 冊 | cè | caak8 | chheh | chaek | tập/sách | saku/satsu/shaku |

| 'bridge' | 橋 | qiáo | kiu4 | kiô | kyo | cầu/kiều | kyō |

| 'dangerous' | 危險 | wēixiǎn | ngai4 him2 | guî-hiám | wiheom | nguy hiểm | kiken |

| 'flag' | 旗 | qí | kei4 | kî | ki | cờ/kỳ | ki |

| 'insurance' | 保險 | bǎoxiǎn | bou2 him2 | pó-hiám | boheom | bảo hiểm | hoken |

| 'news' | 新聞 | xīnwén | san1 man4 | sin-bûn | shinmun | tân văn | shinbun |

| 'student' | 學生 | xuéshēng | hok6 saang1 | ha̍k-seng | haksaeng | học sinh | gakusei |

| university' | 大學 | dàxué | daai6 hok9 | tāi-ha̍k (tōa-o̍h) | daehak | đại học | daigaku |

Culture

Quanzhou was historically the cultural center for Hokkien, as various traditional Hokkien cultural customs such as Nanguan music, Beiguan music, glove puppetry, and the kaoka and lewan genres of Hokkien opera originated from Quanzhou. This was mainly due to the fact that Quanzhou had become an important trading and commercial port since the Tang dynasty and had prospered into an important city. After the Opium War in 1842, Xiamen became one of the major treaty ports to be opened for trade with the outside world. From the mid-19th century onwards, Xiamen slowly developed to become the political and economical center of the Hokkien-speaking region in China. This caused the Amoy dialect to gradually replace the position of dialects from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. From the mid-19th century until the end of World War II, [citation needed] western diplomats usually learned Amoy as the preferred dialect if they were to communicate with the Hokkien-speaking populace in China or Southeast Asia. In the 1940s and 1950s, Taiwan[who?] also tended towards the Amoy dialect.

The retreat of the Republic of China to Taiwan in 1949 drove party leaders to seek to both culturally and politically assimilate the islanders. As a result, laws were passed throughout the 1950s to suppress Hokkien and other languages in favor of Mandarin. By 1956, speaking Hokkien in ROC schools or military bases was illegal. However, popular outcry from both older islander communities and more recent Mainlander immigrants prompted a general wave of education reform, during which these and other education restrictions were lifted. The general goal of assimilation remained, with Amoy Hokkien seen as less 'native', and therefore preferred.[64]

However, from the 1980s onwards, the development of Taiwanese Min Nan pop music and media industry in Taiwan caused the Hokkien cultural hub to shift from Xiamen to Taiwan.[citation needed] The flourishing Taiwanese Min Nan entertainment and media industry from Taiwan in the 1990s and early 21st century led Taiwan to emerge as the new significant cultural hub for Hokkien.

In the 1990s, marked by the liberalization of language development and mother tongue movement in Taiwan, Taiwanese Hokkien had developed quickly. In 1993, Taiwan became the first region in the world to implement the teaching of Taiwanese Hokkien in Taiwanese schools. In 2001, the local Taiwanese language program was further extended to all schools in Taiwan, and Taiwanese Hokkien became one of the compulsory local Taiwanese languages to be learned in schools.[65] The mother tongue movement in Taiwan even influenced Xiamen (Amoy) to the point that in 2010, Xiamen also began to implement the teaching of Hokkien dialect in its schools.[66] In 2007, the Ministry of Education in Taiwan also completed the standardization of Chinese characters used for writing Hokkien and developed Tai-lo as the standard Hokkien pronunciation and romanization guide. A number of universities in Taiwan also offer Taiwanese degree courses for training Hokkien-fluent talents to work for the Hokkien media industry and education. Taiwan also has its own Hokkien literary and cultural circles whereby Hokkien poets and writers compose poetry or literature in Hokkien.

Thus, by the 21st century, Taiwan had become one of the most significant Hokkien cultural hubs of the world. The historical changes and development in Taiwan had led Taiwanese Hokkien to become the most influential pole of the Hokkien dialect after the mid-20th century. Today, the Taiwanese prestige dialect (台語優勢腔/通行腔) is heard on Taiwanese media.

Writing systems

Hokkien texts can be dated back to the 16th century. One example is the Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china, written around 1593 by the Spanish Dominican friars in the Philippines. Another is a Ming dynasty script of a play called Tale of the Lychee Mirror (1566), the earliest known Southern Min colloquial text, which mixes both Hokkien and Teochew.

Chinese script

Hokkien can be written using Chinese characters (漢字; Hàn-jī). However, the written script was and remains adapted to the literary form, which is based on Classical Chinese, not the vernacular and spoken form. Furthermore, the character inventory used for Mandarin (standard written Chinese) does not correspond to Hokkien words, and there are a large number of informal characters (替字; thè-jī, thòe-jī; 'substitute characters') which are unique to Hokkien, as is the case with written Cantonese. For instance, about 20 to 25% of Taiwanese morphemes lack an appropriate or standard Chinese character.[55]

While many Hokkien words have commonly used characters, they are not always etymologically derived from Classical Chinese. Instead, many characters are phonetic loans (borrowed for their sound) or semantic loans (borrowed for their meaning).[67] As example of a phonetic loan character, the word súi meaning "beautiful" might be written using the character 水, which can also be pronounced súi but originally with the meaning of "water". As an example of a semantic loan character, the word bah meaning "meat" might be written using the character 肉, which can also mean "meat" but originally with the pronunciation he̍k or jio̍k. Common grammatical particles are not exempt; the negation particle m̄ is variously represented by 毋, 呣 or 唔, among others. In other cases, new characters have been invented. For example, the word in meaning "they" might be written using the character 𪜶.

Moreover, unlike Cantonese, Hokkien does not have a universally accepted standardized character set. Thus, there is some variation in the characters used to express certain words and characters can be ambiguous. In 2007, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China formulated and released a standard character set to overcome these difficulties.[68] These standard Chinese characters for writing Taiwanese Hokkien are now taught in schools in Taiwan.

Latin script

Hokkien can be written in the Latin script using one of several systems. A popular system is POJ, developed first by Presbyterian missionaries in China and later by the indigenous Presbyterian Church in Taiwan. Use of POJ has been actively promoted since the late 19th century, and it was used by Taiwan's first newspaper, the Taiwan Church News. A more recent system is Tâi-lô, which was adapted from POJ. Since 2006, it has been officially promoted by Taiwan's Ministry of Education and taught in Taiwanese schools. Xiamen University has also developed a system based on Pinyin called Bbánlám pìngyīm. The use of a mixed script of Chinese characters and Latin letters is also seen.

Computing

Hokkien is registered as "Southern Min" per RFC 3066 as zh-min-nan.[69]

When writing Hokkien in Chinese characters, some writers create 'new' characters when they consider it impossible to use directly or borrow existing ones; this corresponds to similar practices in character usage in Cantonese, Vietnamese chữ Nôm, Korean hanja and Japanese kanji. Some of these are not encoded in Unicode, thus creating problems in computer processing.

All Latin characters required by Pe̍h-ōe-jī can be represented using Unicode (or the corresponding ISO/IEC 10646: Universal Character Set), using precomposed or combining (diacritics) characters. Prior to June 2004, the vowel akin to but more open than o, written with a dot above right, was not encoded. The usual workaround was to use an (stand-alone; spaced) interpunct (U+00B7, ·) or less commonly the combining character dot above (U+0307). As these are far from ideal, since 1997 proposals have been submitted to the ISO/IEC working group in charge of ISO/IEC 10646—namely, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2—to encode a new combining character dot above right. This is now officially assigned to U+0358 (see documents N1593, N2507, N2628, N2699 Archived 10 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, and N2713 Archived 14 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine).

Political status

In 2002, the Taiwan Solidarity Union, a party with about 10% of the Legislative Yuan seats at the time, suggested making Taiwanese a second official language.[70] This proposal encountered strong opposition not only from mainland Chinese groups but also from Hakka and Taiwanese aboriginal groups who felt that it would slight their home languages. Because of these objections, support for this measure was lukewarm among moderate Taiwan independence supporters, and the proposal did not pass.

Hokkien was finally made an official language of Taiwan in 2018 by the ruling DPP government.

See also

- Hokkien Kelantan

- Hokkien people

- Languages of China

- Languages of Taiwan

- List of Hokkien dictionaries

- List of Hokkien people

- Amoy Min Nan Swadesh list

Notes

- ^ Many of the 27.7 million Southern Min speakers in mainland China (2018), 13.5 million in Taiwan (2017), 2.02 million in peninsular Malaysia (2000), unknown in Sabah and Sarawak, 1.5 million in Singapore (2017),[1] 1 million in Philippines (2010), 766,000 in Indonesia (2015), 350,000 in Cambodia (2001), 70,500 in Hong Kong (2016), 45,000 in Vietnam (1989), 17,600 in Thailand (1984), 13,300 in Brunei (2004)

- ^ Min is believed to have split from Old Chinese, rather than Middle Chinese like other varieties of Chinese.[3][4][5]

- ^ Not designated but meets legal definition, that is "本法所稱國家語言,指臺灣各固有族群使用之自然語言及臺灣手語。"[7] ("a natural language used by an original people group of Taiwan and the Taiwan Sign Language")

References

- ^ Ethnologue. "Languages of Singapore – Ethnologue 2017". Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ Chinese, Min Nan at Ethnologue (23rd ed., 2020)

- ^ Mei, Tsu-lin (1970), "Tones and prosody in Middle Chinese and the origin of the rising tone", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 30: 86–110, doi:10.2307/2718766, JSTOR 2718766

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1984), Middle Chinese: A study in Historical Phonology, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, p. 3, ISBN 978-0-7748-0192-8

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (10 July 2023). "Glottolog 4.8 - Min". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7398962. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Reclassifying ISO 639-3 [nan]: An Empirical Approach to Mutual Intelligibility and Ethnolinguistic Distinctions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2021.

- ^ 國家語言發展法. law.moj.gov.tw (in Chinese). Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ "Hokkien, adjective & noun". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ West, Barbara A. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Facts on File. pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-0-816-07109-8.

- ^ Táiwān Mǐnnányǔ hànzì zhī xuǎnyòng yuánzé 臺灣閩南語漢字之選用原則 [Selection Principles of Taiwanese Min Nan Chinese Characters] (PDF) (in Chinese), archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2021, retrieved 23 September 2017 – via ws.moe.edu.tw

- ^ a b Douglas, Carstairs (1899). "Extent of the Amoy Vernacular, and its Sub-division into Dialects.". Chinese–English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy (in English & Amoy Hokkien). London: Presbyterian Church of England. p. 609.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Douglas, Carstairs (1899). "Variations of Spelling in Other Books on the Language of Amoy". Chinese–English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy (in English & Amoy Hokkien). London: Presbyterian Church of England. p. 607.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b Macgowan, John (1883). English and Chinese Dictionary of the Amoy Dialect (in English & Amoy Hokkien). London: London Missionary Society.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Li, Rong; Baumann, Theo; Lee, Mei W. (1987). Language Atlas of China. Longman. Map B12. ISBN 978-962-359-085-3.

- ^ a b Douglas, Carstairs (1899). Chinese-English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy. London: Presbyterian Church of England.

- ^ Douglas, Carstairs (1899). Chinese-English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy. London: Presbyterian Church of England.

- ^ a b 張屏生. 《第十屆閩方言國際學術研討會》 (PDF).

- ^ 吳, 守禮. 臺南市福建省同安方言的色彩較濃.

- ^ 吳, 守禮. 經歷台南同安腔與員林漳州腔的異同. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "2010 Population and Household Census in Taiwan" (PDF). Government of Taiwan (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Taiwan Ministry of Education. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Douglas, Carstairs (1899). "Extent of the Amoy Vernacular, and its Sub-division into Dialects.". Chinese–English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy (in English & Amoy Hokkien). London: Presbyterian Church of England. p. 610.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Yan, Margaret Mian (2006). Introduction to Chinese Dialectology. Berlin: LINCOM Europa. p. 120. ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

- ^ a b Chappell, Hilary; Peyraube, Alain (2006). "The analytic causatives of early modern Southern Min in diachronic perspective". In Ho, D.-a.; Cheung, S.; Pan, W.; Wu, F. (eds.). Linguistic Studies in Chinese and Neighboring Languages. Taipei: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica. pp. 973–1011.

- ^ Lien, Chinfa (2015). "Min languages". In Wang, William S.-Y.; Sun, Chaofen (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics. Oxford University Press. pp. 160–172. ISBN 978-0-19-985633-6.

- ^ Klöter, Henning (2011). The Language of the Sangleys: A Chinese Vernacular in Missionary Sources of the Seventeenth Century. BRILL. pp. 31, 155. ISBN 978-90-04-18493-0.

- ^ Yue, Anne O. (1999). "The Min translation of the Doctrina Christiana". Contemporary Studies on the Min Dialects. Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series. Vol. 14. Chinese University Press. pp. 42–76. JSTOR 23833463.

- ^ Van der Loon, Piet (1966). "The Manila Incunabula and Early Hokkien Studies, Part 1" (PDF). Asia Major. New Series. 12 (1): 1–43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Cobo, Juan (1593). Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua China, compuesta por los padres ministros de los Sangleyes, de la Orden de Sancto Domingo (in Early Modern Spanish & Zhangzhou Hokkien). Manila: Keng Yong – via Catálogo BNE (Biblioteca Nacional de España).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c d Lee, Fabio Yuchung; José, Regalado Trota; Caño, José Luis Ortigosa; Chang, Luisa (12 August 2023). "1. Taiwan. Mesa Redonda. Fabio Yuchung Lee, José Regalado, Luisa Chang". Youtube (in Spanish and Mandarin).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Mançano, Melchior; Feyjoó, Raymundo (1620). Arte de la Lengua Chiõ Chiu – via Universitat de Barcelona.

- ^ Zulueta, Lito B. (8 February 2021). "World's Oldest and Largest Spanish-Chinese Dictionary Found in UST". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Van der Loon, Piet (1967). "The Manila Incunabula and Early Hokkien Studies, Part 2" (PDF). Asia Major. New Series. 13 (1): 95–186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Klöter, Henning (2005). Written Taiwanese. Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-3-447-05093-7.

- ^ Medhurst, Walter Henry (1832). A Dictionary of the Hok-këèn Dialect of the Chinese Language, According to the Reading and Colloquial Idioms: Containing About 12,000 Characters. Accompanied by a Short Historical and Statistical Account of Hok-këèn (in English and Hokkien). Macao: The Honorable East India Company's Press, by G.J. Steyn and Brother.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Douglas, Carstairs (1873). Chinese-English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy, with the Principal Variations of the Chang-Chew and Chin-Chew Dialects (in English and Hokkien). 57 & 59 Ludgate Hill, London: Trübner & Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Kane, Daniel (2006). The Chinese Language: Its History and Current Usage. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 100–102. ISBN 978-0-8048-3853-5.

- ^ a b Douglas, Carstairs (1899). "D.". Chinese-English dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy (in English & Amoy Hokkien). London: Presbyterian Church of England. p. 99.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Douglas, Carstairs (1899). "dz". Chinese-English dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy (in English & Amoy Hokkien). London: Presbyterian Church of England. p. 99.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Fang, Meili (2010). Spoken Hokkien. London: SOAS. p. 13.

- ^ Douglas, Carstairs (1899). "L.". Chinese-English dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy (in English & Amoy Hokkien). London: Presbyterian Church of England. p. 288.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Tay, Mary W. J. (1970). "Hokkien Phonological Structure". Journal of Linguistics. 6 (1): 81–88. doi:10.1017/S0022226700002371. JSTOR 4175053. S2CID 145243105.

- ^ Fang, Meili (2010). Spoken Hokkien. London: SOAS. pp. 9–11.

- ^ Zhou, Changji 周長楫 (2006). Mǐnnán fāngyán dà cídiǎn 闽南方言大词典 (in Chinese). Fujian renmin chuban she. pp. 17, 28. ISBN 7-211-03896-9.

- ^ "Shēngdiào xìtǒng" 聲調系統 (in Chinese). 1 August 2007. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2010 – via ntcu.edu.tw.

- ^ Chang, Yueh-chin; Hsieh, Feng-fan (2013), Complete and Not-So-Complete Tonal Neutralization in Penang Hokkien – via Academia.edu

- ^ "Nán'ān fāngyán fùcí fēnxī" 南安方言副词分析. Fujian Normal University. 2010. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Chinese, Min Nan". Ethnologue. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "German". Ethnologue. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ Ratte, Alexander T. (2009). A Dialectal and Phonological Analysis of Penghu Taiwanese (PDF) (BA thesis). Williams College. p. 4.

- ^ Li, Y. C. (1986). "Historical Significance of Certain Distinct Grammatical Features in Taiwanese". In McCoy, John; Light, Timothy (eds.). Contributions to Sino-Tibetan Studies. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 393. ISBN 90-04-07850-9.

- ^ Lien, Chinfa (2002). Grammatical Function Words 乞, 度, 共, 甲, 將 and 力 in Li Jing Ji 荔鏡記 and their Development in Southern Min (PDF). Papers from the Third International Conference on Sinology. National Tsing Hua University: 179–216. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ Klöter, Henning (2005). Written Taiwanese. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05093-7.[page needed]

- ^ Lim, Beng Soon; Teoh, Boon Seong (2007). Alves, Mark; Sidwell, Paul; Gil, David (eds.). Malay Lexicalized Items in Penang Peranakan Hokkien (PDF). SEALSVIII: 8th Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society (1998). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. p. 165.

- ^ Chappell, Hilary; Alain Peyraube. "The Analytic Causatives Of Early Modern Southern Min In Diachronic Perspective" (PDF). Linguistic Studies in Chinese and Neighboring Languages. Paris, France: Centre de Recherches Linguistiques sur l'Asie Orientale: 1–34.

- ^ a b Mair, Victor H. (2010). "How to Forget Your Mother Tongue and Remember Your National Language". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Táiwān Mǐnnányǔ chángyòng cí cídiǎn" 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan]. Ministry of Education, R.O.C. 2011.

- ^ "濕". 17 September 2022 – via Wiktionary.

- ^ "檨". 5 April 2022 – via Wiktionary.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Teochew, another Minnan language – Oung-Heng HENG | PG 2019". YouTube. 19 September 2019.

- ^ "Táiwān Mǐnnányǔ wàilái cí" 臺灣閩南語外來詞 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan] (in Chinese). Taiwan: Ministry of Education, R.O.C. 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ a b Sidong Feidong 似懂非懂 (2006). Pēi nán mì 卑南覓 (in Chinese). Hyweb Technology Co. pp. 1873–. GGKEY:TPZ824QU3UG.

- ^ Thomas Watters (1889). Essays on the Chinese Language. Presbyterian Mission Press. pp. 346–.

- ^ Iûⁿ, Ún-giân. "Tâi-bûn/Hôa-bûn Sòaⁿ-téng Sû-tián" 台文/華文線頂辭典 [Taiwanese/Chinese Online Dictionary]. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Wong, Ting-Hong (May 2020). "Education and National Colonialism in Postwar Taiwan: The Paradoxical Use of Private Schools to Extend State Power, 1944–1966". History of Education Quarterly. 60 (2): 156–184. doi:10.1017/heq.2020.25. S2CID 225917190.

- ^ 《網路社會學通訊期刊》第45期,2005年03月15日. Nhu.edu.tw. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ 有感于厦门学校“闽南语教学进课堂”_博客臧_新浪博客. Sina Weibo. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Klöter, Henning (2005). Written Taiwanese. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05093-7.

- ^ Táiwān Mǐnnányǔ tuījiàn yòng zì (dì 1 pī) 臺灣閩南語推薦用字(第1批) (PDF) (in Chinese), Jiaoyu bu, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2010, retrieved 2 July 2011

- ^ "RFC 3066 Language code assignments". Evertype.com. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ Lin, Mei-chun (10 March 2002). "Hokkien Should Be Given Official Status, Says Tsu". Taipei Times. p. 1.

Further reading

- Branner, David Prager (2000). Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology—the Classification of Miin and Hakka. Trends in Linguistics series, no. 123. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015831-0.

- Chung, Raung-fu (1996). The Segmental Phonology of Southern Min in Taiwan. Taipei: Crane Pub. ISBN 957-9463-46-8.

- DeBernardi, Jean (1991). "Linguistic Nationalism: The Case of Southern Min". Sino-Platonic Papers. 25. OCLC 24810816.

- Ding, Picus Sizhi (2016). Southern Min (Hokkien) as a Migrating Language. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 978-981-287-593-8.

- Francis, Norbert (2014). "Southern Min (Hokkien) as a Migrating Language: A Comparative Study of Language Shift and Maintenance across National Borders by Picus Sizhi Ding (review)". China Review International. 21 (2): 128–133. doi:10.1353/cri.2014.0008. S2CID 151455258.

- Klöter, Henning (2011). The Language of the Sangleys: A Chinese Vernacular in Missionary Sources of the Seventeenth Century. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18493-0. - An analysis and facsimile of the Arte de la Lengua Chio-chiu (1620), the oldest extant grammar of Hokkien.

- Hompot, Sebestyén (2018). Schottenhammer, Angela (ed.). "Xiamen at the Crossroads of Sino-Foreign Linguistic Interaction during the Late Qing and Republican Periods: The Issue of Hokkien Phoneticization" (PDF). Crossroads: Studies on the History of Exchange Relations in the East Asian World. 17/18. OSTASIEN Verlag: 167–205. ISSN 2190-8796. - Chapter examining and detailing the history of Hokkien dictionaries and similar works and the history of Hokkien writing systems over the centuries, especially phonetic scripts for Hokkien

External links

- Lìzhī jì 荔枝記 [Litchi Mirror Tale]. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2015. A playscript from the late 16th century.

- Cobo, Juan, O.P. (1593). Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china. Manila.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Hokkien version of the Doctrina Christiana en lengua española y tagala (1593):- at Biblioteca Nacional de España

- at UST Miguel de Benavidez Library, Manila Archived 8 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- at NCTU, Taiwan Archived 11 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- at Filipinas Heritage Library, Manila

- Mançano, Melchior; Feyjoó, Raymundo (1620). Arte de la Lengua Chio-chiu (in Spanish). Manila. A manual for learning Hokkien written by a Spanish missionary in the Philippines.

- Lūi-chi̍p Ngá-sio̍k-thong Si̍p-ngó͘-im / Huìjí yǎsú tōng shíwǔ yīn 彙集雅俗通十五音 [Compilation of the Fifteen Elegant and Vulgar Sounds] (in Chinese). 1818. The oldest known rhyme dictionary of a Zhangzhou dialect.

- Douglas, Carstairs (1899). Chinese-English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy ("New Edition" (With Chinese Character Glosses) ed.). London: Presbyterian Church of England.