Muhammad I of Granada

| Muhammad I | |

|---|---|

| al-Ghalib biʾllāh | |

.jpg/440px-Muhammad_I_Granada_cropped_CSM_185_(187).jpg) Muhammad I (red tunic and shield) depicted leading his troops during the Mudéjar revolt of 1264–1266 in the Cantigas de Santa Maria | |

| Sultan of Granada[a] | |

| Reign | 1232 – 22 January 1273 |

| Predecessor | None |

| Successor | Muhammad II |

| Born | c. 1195 Arjona, Almohad Caliphate |

| Died | 22 January 1273(1273-01-22) (aged 77–78) near Granada, Emirate of Granada |

| Burial | |

| Issue | Muhammad II of Granada |

| House | Nasrid |

| Religion | Sunni Islam (Maliki) |

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr (Arabic: أبو عبد الله محمد بن يوسف بن نصر, romanized: Muḥammad ibn Yūsuf ibn Naṣr; c. 1195 – 22 January 1273), also known as Ibn al-Ahmar (ابن الأحمر, lit. 'Son of the Red') and by his honorific al-Ghalib billah (الغالب بالله, lit. 'The Victor by the Grace of God'),[2][3] was the first ruler of the Emirate of Granada, the last independent Muslim state on the Iberian Peninsula, and the founder of its ruling Nasrid dynasty. He lived during a time when Iberia's Christian kingdoms—especially Portugal, Castile and Aragon—were expanding at the expense of the Islamic territory in Iberia, called Al-Andalus. Muhammad ibn Yusuf took power in his native Arjona in 1232 when he rebelled against the de facto leader of Al-Andalus, Ibn Hud. During this rebellion, he was able to take control of Córdoba and Seville briefly, before he lost both cities to Ibn Hud. Forced to acknowledge Ibn Hud's suzerainty, Muhammad was able to retain Arjona and Jaén. In 1236, he betrayed Ibn Hud by helping Ferdinand III of Castile take Córdoba. In the years that followed, Muhammad was able to gain control over southern cities, including Granada (1237), Almería (1238), and Málaga (1239). In 1244, he lost Arjona to Castile. Two years later, in 1246, he agreed to surrender Jaén and accept Ferdinand's overlordship in exchange for a 20-year truce.

In the 18 years that followed, Muhammad consolidated his domain by maintaining relatively peaceful relations with the Crown of Castile; in 1248; he even helped the Christian kingdom take Seville from the Muslims. But in 1264, he turned against Castile and assisted in the unsuccessful rebellion of Castile's newly conquered Muslim subjects. In 1266 his allies in Málaga, the Banu Ashqilula, rebelled against the emirate. When these former allies sought assistance from Alfonso X of Castile, Muhammad was able to convince the leader of the Castilian troops, Nuño González de Lara, to turn against Alfonso. By 1272 Nuño González was actively fighting Castile. The emirate's conflict with Castile and the Banu Ashqilula was still unresolved in 1273 when Muhammad died after falling off his horse. He was succeeded by his son, Muhammad II.

The Emirate of Granada, which Muhammad founded, and the Nasrid royal house, lasted for two more centuries until it was annexed by Castile in 1492. His other legacy was the construction of the Alhambra, his residence in Granada. His successors would continue to build the palace and fortress complex and reside there, and it has lasted to the present day as the architectural legacy of the emirate.

Origin and early life

Muhammad ibn Yusuf was born in 1195[4] in the town of Arjona, then a small frontier Muslim town south of the Guadalquivir,[5] now in Spain's province of Jaén. He came from a humble background, and, in the words of the Castilian First General Chronicle, initially he had "no other occupation than following the oxen and the plough".[6] His clan was known as the Banu Nasr or the Banu al-Ahmar.[7] According to later Granadan historian and vizier Ibn al-Khatib, the clan was descended from a prominent companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad known as Sa'd ibn Ubadah of the Banu Khazraj tribe; Sa'd's descendants migrated to Spain and settled in Arjona as farmers.[8] During his early life he became known for his leadership activity on the frontiers and for his ascetic image, which he maintained even after becoming a ruler.[5]

Muhammad was also known as Ibn al-Ahmar,[9] or by his kunya Abu Abdullah.[3]

Family

Muhammad I was married to a paternal first cousin (a bint 'amm marriage), Aisha bint Muhammad, likely in 1230 or before, when he was still in Arjona.[10] Their first son was Faraj (1230 or 1231–1256), whose early death was recorded to cause Muhammad considerable sadness.[11] Their other children included Yusuf (birth unknown), who also died during Muhammad I's lifetime; Muhammad (the future Muhammad II, 1235 or 1236–1302) and two daughters Mu'mina and Shams.[12] He also had a brother, Ismail (d. 1257), whom he appointed as governor of Malaga, and who was the male-line ancestor of a line of future sultans of Granada starting from Ismail I.[13]

Background

The early thirteenth century was a period of great loss for the Muslims of the Iberian Peninsula.[14] The Almohad caliphate, which had dominated Al-Andalus or the Muslim Iberia, was split by a dynastic struggle after Caliph Yusuf II died in 1224 without an heir.[3] Al-Andalus broke up into multiple small kingdoms or taifas.[3] One of the taifa leaders was Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Hud (d. 1238), who revolted against the Almohads and nominally proclaimed the authority of the Abbasid caliphate but in practice ruled independently from Murcia.[15][3] His growing strength made him the de facto leader of Al-Andalus, and briefly Muhammad's overlord.[16] Despite his popularity and his success in Al-Andalus, Ibn Hud had suffered defeats against the Christians, including at Alanje in 1230 and at Jerez in 1231, followed by the loss of Badajoz and Extremadura.[16]

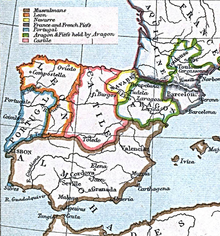

In the north of the peninsula there were several Christian kingdoms: Castile, León (in a union with Castile since 1231), Portugal, Navarre, and a union of kingdoms known as the Crown of Aragon. They had been expanding south—taking formerly Muslim-ruled territories—in a process called the Reconquista or "the reconquest". All of the kingdoms had sizable Muslim minorities.[17] By the mid-thirteenth century, Castile was the largest kingdom of the peninsula.[18] Its king, Ferdinand III (r. 1217–1252) took advantage of the addition of León to his realm and of the Muslims' disunity to launch a southward expansion into Muslim territories, eventually conquering Córdoba (1236) and Seville (1248).[3][19]

Rise to power

The defeats suffered by Ibn Hud eroded his credibility; rebellions broke out in parts of his domain, including Muhammad's small town of Arjona.[9] On 16 July 1232, a mosque assembly in Arjona declared the town's independence. This proclamation took place on 26 Ramadan 629 in the Islamic calendar, after the final Friday prayer of the holy month.[9][20] The assembly elected Muhammad, who was known for his piety and his martial reputation in previous conflicts against the Christians, as the town's leader. Muhammad also had the support of his clan, the Banu Nasr, and an allied Arjonan clan known as the Banu Ashqilula.[21][22][5]

In the same year, Muhammad took Jaén—an important city close to Arjona. With help from Ibn Hud's rivals, the Banu al-Mawl, Muhammad briefly seized control of the former disputed seat of Córdoba. He also took Seville in 1234 with help from the Banu al-Bajji family, but he was only able to hold it for one month. Both Córdoba and Seville, dissatisfied with Muhammad's ruling style, returned to Ibn Hud's rule shortly after Muhammad's takeover. After these failures, Muhammad once again declared his allegiance to Ibn Hud and kept his rule over a small region containing Arjona, Jaén, Porcuna, Guadix, and Baeza.[23][24][5]

Muhammad turned against Ibn Hud again in 1236. He allied himself with Ferdinand and helped the Castilians take Córdoba and end centuries of Muslim rule in the city.[23] In the following years, Muhammad took control of important cities in the south. In May 1237 (Ramadan 634 AH), by invitation of the city's notables, he took Granada, which he then made his capital.[25] He also took Almería in 1238 and Málaga in 1239.[23][26] He did not take these southern cities by force, but through political maneuvering and the consent of the inhabitants.[23][24]

Ruler of Granada

Settling in Granada

Muhammad entered Granada in May 1238 (Ramadan 635).[27] According to Ibn al-Khatib, he entered the city dressed like a sufi, in a plain wool cap, coarse clothes and sandals.[28] He took up residence in the alcazaba (castle) built by the Zirids of Granada in the 11th century.[27] He then inspected an area known as al-Hamra, where there was a small fortress, and laid the foundations there for his future residence and fortress.[29][30] Soon work began on defensive structures, an irrigation dam, and a dike. The construction would last into the reigns of his successors, and the complex would be known as the Alhambra and would become the residence of all Nasrid rulers up to the surrender of Granada in 1492.[31] He pressured his tax collectors to collect the necessary funds for the construction, going as far as executing Almería's tax-gatherer Abu Muhammad ibn Arus to enforce his demands. He also used money sent by the Hafsid ruler of Tunis—intended for defense against the Christians—to extend the city's mosque.[32]

Initial conflict with Castile

.jpg/440px-Alhamar,_rey_de_Granada,_rinde_vasallaje_al_rey_de_Castilla,_Fernando_III_el_Santo_(Museo_del_Prado).jpg)

By the end of the 1230s, Muhammad had become the most powerful Muslim ruler in Iberia. He controlled the major cities of the south, including Granada, Almería, Málaga and Jaén. In the early 1240s, Muhammad came into conflict with his former allies, the Castilians, who were invading Muslim territories. Contemporary sources disagree about the cause of this hostility: the Christian First General Chronicle blamed it on Muslim raiding, while Muslim historian Ibn Khaldun blamed it on Christian invasions of Muslim territories. In 1242, Muslim forces successfully raided Andújar and Martos near Jaén. In 1244, Castile besieged and captured Muhammad's hometown of Arjona.[33]

In 1245, Ferdinand III of Castile besieged the heavily fortified Jaén. Ferdinand did not want to risk assaulting the city, so his tactic was to cut it off from the rest of the Muslim territory and starve it into submission. Muhammad tried to send supplies to this important city, but these efforts were thwarted by the besiegers. Due to Muhammad's difficulty in defending and relieving Jaén, he agreed to terms with Ferdinand. In exchange for peace, Muhammad surrendered the city and agreed to pay Ferdinand an annual tribute of 150,000 maravedíes—an amount that became Ferdinand's most important source of income.[34][35] This agreement was made in March 1246, seven months into the siege of Jaén. As part of the agreement he was required to kiss Ferdinand's hand to signify his vassalage, and promised him "counsel and aid".[36] Castilian sources tended to emphasize this event as an act of feudal submission and considered Muhammad and his successors as vassals of Castile in the feudal sense.[36][37] On the other hand, Muslim sources avoided mentions of any vassal-lord relation and tended to frame the relationship as between equals with certain obligations.[36][38] After the agreement, the Castilians entered the city and expelled its Muslim inhabitants.[39][40]

Peace

The peace agreement with Castile largely held for almost twenty years. In 1248, Muhammad demonstrated his commitment to Ferdinand by sending a contingent to help the Castilian conquest of the Muslim-held Seville. In 1252, Ferdinand died and was succeeded by Alfonso X. In 1254, Muhammad attended a Cortes, or an assembly of Alfonso's vassals, at the royal palace in Toledo, where he renewed his promise of loyalty and tributes, as well as paying homage to Alfonso's newborn daughter Berengaria. During his reign, Alfonso was more interested in other enterprises—including a series of unsuccessful campaigns in Muslim North Africa—rather than renewing the conflict with Granada. Muhammad met with Alfonso at the latter's court in Seville every year, and paid his annual tributes. Muhammad used the ensuing peace to consolidate his new emirate. Though small in size, the Emirate of Granada was relatively wealthy and densely populated. Its economy was focused on agriculture, especially silk and dried fruit; it traded with Italy and northern Europe. Islamic literature, art and architecture continued to flourish. The mountains and desert that separate the kingdom from Castile provided natural defenses, but its western ports and the northwestern route to Granada were less defensible.[41][42][43][44]

During his rule, Muhammad placed loyal men in castles and cities.[45] His brother Isma'il was governor of Málaga until 1257.[45] Following Isma'il's death in 1257, Muhammad appointed his nephew, Abu Muhammad ibn Ashqilula, as governor of Málaga.[45]

Rift with Castile

Peace between Granada and Castile lasted until the early 1260s, when various actions by Castile alarmed Muhammad.[46] As part of his crusade against Muslim North Africa, Alfonso built up his military presence in Cadiz and El Puerto de Santa María close to Granadan territory.[47][46] Castile conquered the Muslim-held Jerez de la Frontera in 1261 near the Granadan border and installed a garrison there.[48][46] In 1262, Castile conquered the Kingdom of Niebla, another Muslim enclave in Spain.[46][49] In May 1262, during a meeting in Jaén, Alfonso requested that Muhammad hand the port cities of Tarifa and Algeciras to him.[50] The demand for these strategically important ports was very worrying to Muhammad, and although he verbally agreed he kept delaying the transfer.[50][46] Further, in 1263 Castile expelled the Muslim inhabitants of Écija and resettled the town with Christians.[50]

In light of these actions, Muhammad was worried that he would become Alfonso's next target.[46] He began talks with Abu Yusuf Yaqub, the Marinid Sultan in Morocco, who then sent troops to Granada, numbering between 300 and 3,000 according to different sources.[51] In 1264, Muhammad and 500 knights traveled to the Castilian court at Seville to discuss an extension of the 1246 truce.[52] Alfonso invited them to lodge at the former Abbadid palace next to the city's mosque.[52] During the night, the Castilians locked and barricaded the area.[52] Muhammad perceived this as a trap, ordered his men to break out and returned to Granada.[52] Alfonso argued that the barricade was to protect the entourage from Christian thieves, but Muhammad was angered, and ordered troops in his border towns to prepare for war.[52] He declared himself vassal of Muhammad I al-Mustansir, the Hafsid sultan of Tunis.[52]

Revolt of the Mudéjars

The peace was broken in either late April or early May 1264.[53] Muhammad attacked Castile, and at the same time Muslims in the territories recently conquered by Castile ("Mudéjars") rebelled; partially over Alfonso's forced relocation policy and partially at Muhammad's instigation. Initially, Murcia, Jerez, Utrera, Lebrija, Arcos and Medina Sidonia were taken into Muslim control, but counterattacks by James I of Aragon and Alfonso retook these territories, and Alfonso invaded Granada's territory in 1265. Muhammad soon sued for peace, and the resulting settlement was devastating for the rebels: the Muslims of Andalusia suffered mass expulsions, replaced by Christians.[54][55]

For Granada, the defeat had mixed consequences. On the one hand, it was soundly defeated, and according to the peace treaty signed at Alcalá de Benzaide had to pay an annual tribute of 250,000 maravedíes to Castile—much larger than what had been paid before the rebellion.[56] On the other hand, the treaty ensured its survival, and it emerged as the sole independent Muslim state in the peninsula.[57] Muslims who were expelled by Castile immigrated to Granada, bolstering the emirate's population.[57]

Conflict with the Banu Ashqilula

The Banu Ashqilula were a clan and—like the Nasrids—were also from Arjona. They had been the Nasrids' most important allies during their rise to power. They supported Muhammad's appointment as leader of Arjona in 1232 and helped with the acquisition of cities like Seville and Granada. Both families intermarried, and Muhammad appointed members of the Banu Ashqilula as governors in his territories. The Banu Ashqilula's center of power was in Málaga, where Muhammad's nephew Abu Muhammad ibn Ashqilula was governor. Their military strength was the backbone of Granada's power.[58]

By 1266, while Granada was still fighting Castile in the Mudéjar revolt, the Banu Ashqilula started a rebellion against Muhammad I.[59][60][61] Sources are scarce regarding the beginning of the rebellion and historians disagree about the cause of the rift between the two families. Professor of Hispano-Islamic history Rachel Arié suggested that contributing factors may have been the 1257 declaration of Muhammad's sons—Muhammad and Yusuf—as heirs and his 1266 decision to marry one of his granddaughter Fatima [62]to a Nasrid cousin instead of one of the Banu Ashqilula. According to Arié, these decisions alarmed the Banu Ashqilula because Muhammad had previously promised to share power with them and these decisions excluded them from the Nasrid dynasty's inner circle. In contrast, another historian of Islamic Spain, María Jesús Rubiera Mata rejected these explanations; she argued that the Banu Ashqilula were worried about Muhammad's decision to invite North African forces during the 1264 Revolt of the Mudéjars because the new military power threatened the Banu Ashqilula's position as the strongest military power in the Emirate.[62]

Muhammad besieged Málaga but failed to overpower the Banu Ashqilula military strength.[60] The Banu Ashqilula sought assistance from Alfonso X of Castile, who was happy to support the rebellion to undermine Muhammad's authority.[60] Alfonso sent 1,000 soldiers under Nuño González de Lara and Muhammad was forced to break off the siege of Málaga.[60] The danger of fighting at multiple fronts contributed to Muhammad's decision to finally seek peace with Alfonso.[63] In the resulting agreement of Alcalá de Benzaide, Muhammad renounced his claims over Jerez and Murcia—territories not under his control—and promised to pay an annual tribute of 250,000 maravedies.[60][56] In exchange, Alfonso abandoned his alliance with the Banu Ashqilula and acknowledged Muhammad's authority over them.[60]

Alfonso was reluctant to enforce the last point and did not move against the Banu Ashqilula. Muhammad countered by convincing Nuño González, the commander of the Castilian forces sent to support the Banu Ashqilula, to rebel against Alfonso. Nuño González, who had grievances against his king, agreed; in 1272 he and his Castilian noble allies began operations against Castile from Granada. Muhammad had successfully deprived Castile of Nuño González's forces and gained allies in his conflict against the Banu Ashqilula. The Banu Ashqilula agreed to negotiate under the mediation of Al-Tahurti from Morocco.

Before these efforts bore fruit, Muhammad suffered fatal injuries after falling from a horse on 22 January 1273 (29 Jumada al-Thani 671 AH),[64][59][65] near the city of Granada during a minor military expedition.[66] He was buried in a cemetery on the Sabika Hill, east of the Alhambra.[67] An epitaph was inscribed on his headstone and was recorded by Ibn al-Khatib and other historical sources.[67] He was succeeded by his son Muhammad II as he had planned.[34] Later that year, Muhammad II and Alfonso negotiated a truce—albeit short-lived—between Granada and Castile as well as the Banu Ashqilula.[68]

Succession

By the time of his death in 1273, Muhammad had already secured the succession for his son, also named Muhammad, known by the epithet al-Faqih (the canon-lawyer). On his deathbed, Muhammad I advised his heir to seek protection from the Marinid dynasty against the Christian kingdoms.[34] The son, now Muhammad II, was already 38 years old and experienced in the matters of state and war. He was able to continue Muhammad I's policies and would rule until his death in 1302.[66][59]

Legacy

.jpg/440px-Arjona_-_008_(30621654032).jpg)

Muhammad's main legacy was the founding of the Emirate of Granada under the rule of the Nasrid dynasty, which on his death was the only independent Muslim state remaining in the Iberian peninsula,[69] and would last for little over two centuries before its fall in 1492. The emirate spanned 240 miles (390 km) between Tarifa in the west and eastern frontiers beyond Almería, and was around 60 to 70 miles (97 to 113 km) wide from the sea to its northern frontiers.[69]

During his lifetime, the Muslims of al-Andalus suffered severe setbacks, including the loss of the Guadalquivir valley, which included the major cities of Córdoba and Seville as well as Muhammad's hometown of Arjona.[70] According to professor of Spanish history L. P. Harvey, he "managed to snatch from disaster ... a relatively secure refuge for Islam in the peninsula".[70] His rule was characterized both by his "unheroic" part in the fall of Muslim cities like Seville and Jaén, as well his vigilance and political astuteness which ensured the survival of Granada.[70] He was willing to enter into compromises, including accepting vassalage to Castile, as well as to switch alliances between Christians and Muslims, to preserve the emirate's independence.[70][5] The Encyclopaedia of Islam comments that while his rule did not have any "spectacular victories", he did create a stable regime in Granada and start the construction of the Alhambra, a "lasting memorial to the Nasrids".[5] The Alhambra is today a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[71]

His religious views appeared to transform during his career. In the beginning, he displayed an outward image of an ascetic religious frontiersman, like a typical Islamic mystic. He maintained this outlook during his early rule in Granada, but as his rule stabilized, he began to embrace the mainstream Sunni orthodoxy and enforced the doctrines of the Maliki fuqaha. This transformation and his commitment to mainstream Islam brought Granada into line with the rest of the Islamic world, and were continued by his successors.[5][70]

Notes

- ^ In addition to sultan, the titles of king and emir (Arabic: amir) are also used in official documents and by historians.[1]

References

Citations

- ^ Rubiera Mata 2008, p. 293.

- ^ Vidal Castro 2000, p. 802.

- ^ a b c d e f Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, p. 1020.

- ^ Vidal Castro 2000, p. 798.

- ^ a b c d e f g Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, p. 1021.

- ^ Harvey 1992, p. 28.

- ^ Harvey 1992, p. 21.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2014, p. 274.

- ^ Boloix Gallardo 2017, p. 38.

- ^ Boloix Gallardo 2017, p. 163.

- ^ Boloix Gallardo 2017, pp. 38, 165.

- ^ Fernández-Puertas 1997, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Harvey 1992, p. 9.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 265.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2014, pp. 268, 274.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Harvey 1992, p. 6.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Vidal Castro 2000, p. 806.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, pp. 267, 274.

- ^ a b c d Harvey 1992, p. 22.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2014, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, pp. 1020–1021.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 275.

- ^ a b Terrasse 1965, p. 1016.

- ^ Harvey 1992, p. 29.

- ^ Terrasse 1965, pp. 1014, 1016.

- ^ Latham & Fernández-Puertas 1993, p. 1028.

- ^ Terrasse 1965, pp. 1016–1017.

- ^ Terrasse 1965, p. 1014.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c Miranda 1970, p. 429.

- ^ Doubleday 2015, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Catlos 2018, p. 334.

- ^ Harvey 1992, p. 26.

- ^ Harvey 1992, p. 30.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, p. 276.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, pp. 277–278.

- ^ Harvey 1992, p. 25.

- ^ Doubleday 2015, p. 60.

- ^ O'Callaghan 2011, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Fernández-Puertas 1997, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f O'Callaghan 2011, p. 34.

- ^ O'Callaghan 2011, p. 23.

- ^ O'Callaghan 2011, p. 29.

- ^ O'Callaghan 2011, p. 31.

- ^ a b c O'Callaghan 2011, p. 32.

- ^ O'Callaghan 2011, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b c d e f O'Callaghan 2011, p. 35.

- ^ O'Callaghan 2011, p. 36.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Doubleday 2015, p. 122.

- ^ a b Harvey 1992, p. 51.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 31–33.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2014, p. 279.

- ^ a b c d e f Harvey 1992, p. 38.

- ^ O'Callaghan 2011, p. 48.

- ^ a b Harvey 1992, p. 33.

- ^ O'Callaghan 2011, p. 49.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Diem & Schöller 2004, p. 434.

- ^ a b Harvey 1992, p. 39.

- ^ a b Diem & Schöller 2004, p. 432.

- ^ Harvey 1992, pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b Watt & Cachia 2007, p. 127.

- ^ a b c d e Harvey 1992, p. 40.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage List, 314-001

Sources

- Boloix Gallardo, Bárbara (2017). Ibn al-Aḥmar: vida y reinado del primer sultán de Granada (1195–1273) (in Spanish). Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada. ISBN 978-84-338-6079-8.

- Catlos, Brian A. (July 2018). Kingdoms of Faith: A New History of Islamic Spain. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1787380035.

- Diem, Werner; Schöller, Marco (2004). The Living and the Dead in Islam: Epitaphs as texts. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05083-8.

- Doubleday, Simon R. (1 December 2015). The Wise King: A Christian Prince, Muslim Spain, and the Birth of the Renaissance. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465073917.

- Fernández-Puertas, Antonio (April 1997). "The Three Great Sultans of al-Dawla al-Ismā'īliyya al-Naṣriyya Who Built the Fourteenth-Century Alhambra: Ismā'īl I, Yūsuf I, Muḥammad V (713–793/1314–1391)". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Third Series. 7 (1). London: 1–25. doi:10.1017/S1356186300008294. JSTOR 25183293. S2CID 154717811.

- Harvey, L.P. (1992). "The Rise of Banu'l-Ahmar". Islamic Spain, 1250 to 1500. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. pp. 20–40. ISBN 978-0226319629.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2014). Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of Al-Andalus. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317870418.

- Latham, John Derek & Fernández-Puertas, Antonio (1993). "Nasrids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1020–1029. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Miranda, Ambroxio Huici (1970). "The Iberian Peninsula and Sicily". In Holt, P.M.; Lambton, Ann K.S.; Lewis, Bernard (eds.). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 2A. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 406–439. ISBN 978-0521219488.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (1998). Alfonso X and the Cantigas De Santa Maria: A Poetic Biography. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004110236.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (2011). The Gibraltar Crusade: Castile and the Battle for the Strait. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 34–59. ISBN 978-0812204636.

- Rubiera Mata, María Jesús (2008). "El Califato Nazarí". Al-Qanṭara (in Spanish). 29 (2). Madrid: Spanish National Research Council: 293–305. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2008.v29.i2.59.

- Terrasse, Henri (1965). "Gharnata". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1012–1020. OCLC 495469475.

- Vidal Castro, Francisco (2000). "Frontera, genealogía y religión en la gestación y nacimiento del Reino Nazarí de Granada: En torno a Ibn al-Aḥmar" (PDF). III Estudios de Frontera: Convivencia, defensa y comunicación en la Frontera (in Spanish). Jaén: Diputación Provincial de Jaén. pp. 794–810. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- Watt, W. Montgomery; Cachia, Pierre (2007) [1967]. "The Last of Islamic Spain 1. The Nasrids of Granada". A History of Islamic Spain. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. pp. 127–142. ISBN 978-0202309361.