Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Status | Proposed |

| Crosses | New York Harbor |

| Start | Jersey City, New Jersey |

| End | Bay Ridge Brooklyn, New York |

| Technical | |

| Length | 30,000 ft (9.1 km) portal-to-portal[1]: 4–32 |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

The Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel (also known as the Cross Harbor Rail Freight Tunnel) is a proposed freight rail transport tunnel under Upper New York Bay in the Port of New York and New Jersey between northeastern New Jersey and Long Island, including southern and eastern New York City.

In November 2014, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey released a Tier 1 Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for its Cross Harbor Freight Program.[1] It reviewed four waterborne and four tunnel alternatives. Estimated costs for the waterborne alternatives ranged from $95 to 190 million, and from $7 to 11 billion for the tunnel alternatives. On September 25, 2015, the Tier 1 Final Environmental Impact Statement was released,[2] which narrowed the alternatives to two, an enhanced railcar float operation and a basic rail tunnel, both between New Jersey and Brooklyn. A phased plan starting with building the enhanced car float was proposed.

In early May 2017, the Port Authority issued a Request for Proposals (RFP) for a “Tier II” Environmental Impact Study of the rail tunnel and enhanced railcar float alternatives.[3] A $23.7 million, three-year contract for the Tier II study was awarded in early 2018.[4] The Tier II study was suspended during the COVID-19 crisis, but was restarted in February 2022.[5]

History

Direct connections for rail freight between Long Island and nearby areas of the United States have long been limited. At present, freight trains from the west and south destined for New York City (except for Staten Island, via the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge), Long Island and Connecticut must cross the Hudson River using the Alfred H. Smith Memorial Bridge which is 140 miles (225 km) north of New York City at Selkirk, New York, making a 280-mile (451 km) detour known as the "Selkirk hurdle." Partly as a result, less than 3% by weight of the area's freight is said to move by rail. The former Pennsylvania Railroad planned a freight railroad tunnel between Brooklyn and Staten Island in 1893, but the project was never carried out. Attempts by government planners to revive the project from the 1920s through the 1940s did not succeed.[6] The Pennsylvania Tunnel and Terminal Railroad tunnels through New York Penn Station, generally used only for passenger trains, were used briefly for freight during World War I to relieve congestion at the barge transport docks, but today's passenger and commuter traffic frequencies are at capacity and preclude freight movements.[7] Proposals for a cross-harbor tunnel were floated as early as the 1920s.[8]

In the early 1990s, U.S. Representative Jerrold Nadler revived interest in direct connection of rail freight to Long Island, hoping to reduce truck traffic through Manhattan.[9] With support from the City government, the New York City Economic Development Corporation commissioned a study of rail freight traffic across New York Harbor. The Cross Harbor Freight Movement Major Investment Study received $4 million from the U.S. Department of Transportation and $1 million from the New York City Industrial Development Agency.[10] Edwards and Kelcey,[11] a transportation engineering firm in Morristown, NJ, was hired to study the feasibility of alternative approaches to increased rail access for freight.

The idea of a cross-harbor rail tunnel also received support from Connecticut transportation planners, who believed such a rail connection would reduce truck traffic on the heavily congested Connecticut Turnpike.[12]

The proposed tunnel would primarily serve Long Island, which includes the New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens as well as Nassau and Suffolk counties, with a combined population of 7.7 million. It is served by the Long Island Rail Road, the busiest commuter railroad in North America. Rail freight service on Long Island is provided by the New York and Atlantic railroad (NYA), which operates on LIRR tracks and carries about 30,000 carloads each year.[13] The NYA connects with CSX Transportation via the Hell Gate Bridge to CSX Transportation's Oak Point Yard in the Bronx. It also connects to CSX and Norfolk Southern in the Greenville section of Jersey City, NJ, via a cross harbor float barge service, the New York New Jersey Rail, LLC, currently owned by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

The New York City boroughs of the Bronx and Staten Island have active rail freight connections, via the Oak Point Link and the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge, respectively. The latter connects Staten Island with rail lines west of the Hudson, and serves the Howland Hook Marine Terminal and a municipal waste facility, but there are no rail connections between Staten Island and the rest of New York City or Long Island. Manhattan last saw freight service in 1983.[14] The West Side freight line was partially converted to passenger service to Pennsylvania Station in 1991, with the West Side freight yards replaced by Riverside South and the elevated portion south of 30th street converted into High Line Park.

Feasibility and environmental issue studies

In its summer 2000 report, Edwards and Kelcey evaluated proposals for rail tunnels between Brooklyn and Staten Island and between Brooklyn and Jersey City, plus increased barge transport of railcars across New York Harbor. It estimated a pair of tunnels between Jersey City and Brooklyn to cost $2.15 billion, not including track connections or track improvements. Despite the length of the tunnels being considered, up to 17,000 ft (5,182 m) under water, the study found that providing enough ventilation to operate diesel locomotives would be practical.[15]

Probably mindful of environmental issues that were key elements in the 1985 cancellation of the Westway project, the New York City Industrial Development Agency commissioned an environmental assessment. This assessment found that immersed tube construction would be environmentally more hazardous and more expensive than bored tunnel construction. Ventilation was confirmed as practical and found unlikely to present greater hazards than fumes from trucks that would otherwise be used to transport freight.[6]

Following the feasibility and environmental studies, two organizations were formed to plan and promote a tunnel project and to seek government funding. They are the Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project,[16] hosted by the STV Group,[17] a construction firm in New York City and Douglassville, Pennsylvania, and the Cross-Harbor Tunnel Coalition,[18] also known as "MoveNYNJ" or "Move NY & NJ". The Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project is supported by funds from the U.S. Federal Highway Administration, the U.S. Federal Railroad Administration and the New York City Economic Development Corporation, while the Cross-Harbor Tunnel Coalition is a voluntary organization of business, union and political leaders. Political activity led to authorization of $100 million for a Cross Harbor Rail Freight Tunnel as a federal transportation project in the U.S. Transportation Equity Act of 2005.[19]

2014 Draft Environmental Impact Study

The 2014 Tier 1 Draft Environmental Impact Study[20] (DEIS) considered 29 alternatives and selected ten for further study, including five tunnel options and five waterborne options. The tunnel options considered include the following:

- Rail tunnel

- Rail tunnel with shuttle service from Pennsylvania

- Rail tunnel with "Chunnel" service patterned after the truck movement system used on the England-France Channel Tunnel

- Rail tunnel with Automated Guided Vehicles

- Rail and truck tunnel shared 12 hours for trucks and 12 hours for rail

The waterborne options include enhanced rail float operations, going beyond what the improvements the Port Authority has already committed to, and four options involve transporting trucks or shipping containers across the harbor by boat. The latter group includes

- Truck float

- Truck ferry

- Lift on lift off (LOLO) – lifting containers on and off a barge

- Roll on roll off (RORO) – a vessel designed to allow wheeled trucks or trailers to be driven onboard

The DEIS Executive Summary (Table ES-6) lists the following costs and benefits for the various options:

| Metric | Enhanced rail float | Truck waterborne | Rail tunnels | Rail+truck shared tunnel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction cost (millions of 2012 dollars) | $142 | $95 – $190 | $6,927 – $10,790 | $7,815 – $10,875 |

| Freight diversion (million tons/yr) | 0.5–2.8 | 0.3–1.7 | 7.2–10.5 | 24.1 |

| Reduction in cross harbor truck traffic | 0.8% | 0.8% | 2% – 3.7% | 8% |

| Shipper savings (millions of 2012 dollars) | $143 – $196 | < $1 | $621 – $646 | $636 |

Only the enhanced rail float and the basic rail tunnel options were selected in the Final EIS for Tier II analysis.

Facilities

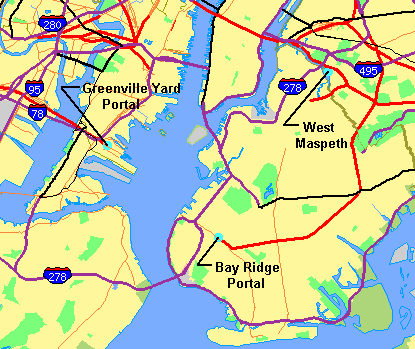

The proposed Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel tubes would be large enough to take double-stacked container cars.[21][a] According to the Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project, the alignment favored for a Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel is between portals (access points) located in Conrail's Greenville Yard in Jersey City and along the Long Island Rail Road's Bay Ridge Branch in Brooklyn, crossing the middle of the Upper Harbor, with a length of 5.7 mi (9.2 km).[1]: 4–32

Other infrastructure

During the environmental assessment, existing rail infrastructure was surveyed for compatibility with a Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel. Parts of the existing trackage need repair. Some rights of way have been reduced to single-track width or were never wider and are in deteriorating condition due to their little use and maintenance. Nearly all track segments lack enough clearance above the tracks for the envisaged double-stacked container cars.[22][23] Such factors limit the effective capacity of a rail tunnel and will add substantial cost to overcome. Rail yards east of New York Harbor lack a trans-shipment terminal with enough capacity to transfer the freight coming through a Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel to trucks. A proposal was generated to acquire 100 acres (40 ha) of land to build one in West Maspeth, Queens.[24] Studies performed for the Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel say about 30,000 trucks per day cross the George Washington Bridge and the Verrazano Narrows Bridge going to or from parts of Long Island, including Queens and Brooklyn, or about 10 million trucks per year.

2015 Final Tier I Draft Environmental Impact Statement

The Final Tier I Draft Environmental Impact Statement recommends further study of two alternatives: enhanced rail float operations and the most basic rail tunnel among the tunnel alternatives. While the rail float alternative is expected to produce less freight tonnage diversion than the tunnel (2.8 million tons per year vs 9.6), its costs are dramatically less, $175 million vs. $7.2 billion. The EIS recommends a phased approach, starting by building enhanced float service for carload freight, adding capacity for intermodal traffic, developing needed intermodal facilities on Long Island and finally planning and building the rail freight tunnel.[2]

Port Authority Chairman John J. Degnan expressed doubts about the freight rail tunnel alternative in light of competing demands on Port Authority resources, including the Gateway Project passenger rail tunnel under the Hudson, which is estimated to cost $20 billion, and a new Port Authority Bus Terminal costing up to $10 billion. "It's hard for me to imagine, given the competing demands for the federal government fund for other projects, that it would commit to funding at a cost on that order of magnitude."[25]

Tier II efforts

In July 2017, the Port Authority announced it had allocated $35 million to the study of the tunnel suitable for freight.[26] In February 2018, the Port Authority awarded a $23.7 million contract to Cross Harbor Partners, a joint venture of STV Incorporated and AKRF Inc., to develop a Tier II Environmental Impact Statement. The Tier II process is expected to take three years.[4]

Criticism

Some critics object that improving rail transport with a tunnel would provide little traffic reduction relative to its high cost.[27] The West Maspeth facility has been heavily criticized. It is proposed for an industrial site about four blocks south of the interchange between the Long Island Expressway (I-495) and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (I-278), where Nichols Copper and later Phelps Dodge operated a copper refinery for decades. The copper plant closed in 1983, and the site has been largely vacant since then, although a new food warehouse was completed at its eastern end in 2005. It abuts the heavily polluted Newtown Creek.[28]

Although the Cross-Harbor tunnel terminal site is close to two major highways and existing rail, many access routes pass through residential neighborhoods. Based on the estimates of the rail tunnel's capacity, traffic to and from the site could reach thousands of truck trips per day. However, most of those trucks already travel through those highways to use the existing bridge connection.

Spokespersons for neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens strongly object to land being designated for a trans-shipment terminal or other railroad uses[29] and to the noise and vibration expected from passage of up to 1,600 rail cars per day.[30] Reacting to these criticisms, in March 2005 New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced that he opposed the rail tunnel project.[31] However, in early July 2007, Mayor Bloomberg told Rep. Nadler he would be willing to take another look at the plan.[32]

A City University of New York study, published in 2011, pointed out that "no current demand for a containerized truck-rail facility has yet been demonstrated" on Long Island, in part because long-distance trucks, including intermodal containers, generally must be unloaded at major distribution centers which typically serve an entire metropolitan area. Few such distribution centers are located on Long Island.[33] The study also noted that standard double stack rail equipment is too wide to run on tracks where third rail is used, as it is on much of the Long Island Rail Road's passenger routes.[34]

Concern has been expressed about the project's impact on Port Authority toll revenue.[35]

The proposed "MoveNY" transportation plan[36] would use right-of-way needed for the tunnel project, including the Bay Ridge branch, to build a new Triboro RX subway service connecting The Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn, potentially interfering with the right-of-way's use for rail freight. A feasibility study for the Interborough Express project, which would implement part of the Triboro RX route, indicated that both projects could potentially co-exist.[37][38]

Former executive director of the PANYNJ, Christopher O. Ward has come out forcefully against the project.[39]

See also

- Interborough Express, proposed passenger rail service between Brooklyn and Queens that would use existing rail freight right of way

- New York and Atlantic Railway, the current freight railroad operator on Long Island.

- New York Cross Harbor Railroad, a car float (rail barge transport) operation between Jersey City and Brooklyn.

- New York New Jersey Rail, LLC, the current car float operation.

- New York Tunnel Extension, the passenger tunnels to New York Penn Station.

- Rail freight transportation in New York City and Long Island, overview of historic and existing operations in the area

- Staten Island Tunnel, a subway extension abandoned in 1925

References

Notes

- ^ The diameter of a two-lane tube for the Holland Tunnel is slightly less than the diameter for a tube with one rail line in a Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel.[6]

Citations

- ^ a b c "Cross Harbor Freight Program: CHFP Tier 1 EIS Document". panynj.gov. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018.

- ^ a b "Cross Harbor Freight Program: CHFP final Tier 1 EIS Document". panynj.gov. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016.

- ^ Frost, Mary (May 8, 2017). "RFP to study Cross-Harbor Rail Freight Tunnel connecting NJ and Brooklyn". Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

- ^ a b "NY/NJ Cross Harbor Freight Program Enters Second Review Phase". Maritime Professional. February 9, 2018.

- ^ Gerberer, Raanan (February 9, 2022). "EIS to resume on long-delayed Cross-HarborFreight Program". Brooklyn Eagle.

- ^ a b c Mainwaring, Gareth (2002). "The development of the New York Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project" (PDF). Toronto, ON: Hatch Mott Macdonald. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2005.

- ^ Baer, Christopher T., ed. (June 2004). "PRR Chronology" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 20, 2011.

- ^ "SAYS ROADS BLOCK PORT UNIFICATION; Van Buskirk Discusses Authority's Project Before JerseyCity Kiwanians.EXPLAINS BELT LINE PLANCommissioner Indicates That NoParticular Rall Line Can LongPrevent the Work" (PDF). The New York Times. November 24, 1922.

- ^ Nadler, Jerrold (1993). "HR 2784, New York Harbor Tunnel Act of 1993". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012.

- ^ "NYCEDC - New York City Industrial Development Agency". newyorkbiz.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006.

- ^ "Edwards and Kelcey". Archived from the original on May 18, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ "Connecticut Turnpike". Archived from the original on June 24, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- ^ "New York and Atlantic Railway". Anacostia & Pacific Company, Inc.

- ^ Kinlock, Ken. "West Side Freight Line into Manhattan: The High Line". kinglyheirs.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016.

- ^ Carey, Michael G. (2000). "Cross Harbor Freight Movement Major Investment Study" (PDF). New York City Economic Development Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2003.

- ^ "The Port Authority of NY & NJ". crossharborstudy.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2004.

- ^ "Corporate Offices". STV Group. Archived from the original on April 28, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ "Cross-Harbor Tunnel Coalition". Move NY & NJ. Archived from the original on June 17, 2006.

- ^ McGregor, Marnie (July 29, 2005). "Cross Harbor Tunnel receives significant funding in federal transportation bill". Move NY & NJ. Cross-Harbor Tunnel Coalition. Archived from the original on June 20, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ "CHFP Tier 1 EIS Document". Cross Harbor Freight Program. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Steve (2006). "Holland Tunnel historic overview". NYCRoads.com. Eastern Roads.

- ^ Orcutt, Jon; Slevin, Kate (May 17, 2004). "Long-Awaited Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel Environmental Report Released" (PDF). Tri-State Transportation Campaign. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 10, 2005. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ Dredged Material Management Interagency Workgroup (February 5, 2003). "Meeting Notes" (PDF). NY/NJ Clean Ocean And Shore Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2005. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project (2004). "Brief History of Cross Harbor Rail". Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ Strunsky, Steve (September 25, 2015). "The $7.4B freight tunnel that could ease tri-state area traffic". nj.com.

- ^ Geiger, Daniel (July 14, 2017). "With Gateway in limbo, Port Authority pushes ahead on separate tunnel project". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- ^ Samuel, Peter (September 29, 2004). "New York harbor rail tunnel pushed with special truck toll tax". Toll Roads Newsletter. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ^ Stockstill, Laura (March 3, 2005). "Planning Industrial Futures in West Maspeth". Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance. Archived from the original on June 23, 2006.

- ^ McKay, Rob (September 30, 2004). "Rally Rips Freight Tunnel Plan". Queens, NY: Ridgewood Times Newsweekly. Archived from the original on March 14, 2005.

- ^ King, Leo (December 6, 2004). "Freight Lines: New Yorkers hear tunnel objections". National Corridors Initiative. Archived from the original on April 6, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ Cargin, David (March 10, 2005). "Mayor Bloomberg Opposes Cross Harbor Freight Tunnel". Queens Chronicle, Mid-Queens Edition. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ Colangelo, Lisa L. (July 10, 2007). "Dig it! Bloomy waffles on tunnel". Daily News, City Hall Bureau. New York. Archived from the original on July 12, 2007.

- ^ Paaswell, Robert E.; Eickemeyer, Penny (June 9, 2011). "NYSDOT Consideration of Potential Intermodal Sites for Long Island" (PDF). CUNY Institute for Urban Systems University Transportation Research Center. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ Paaswell & Eickemeyer 2011, p. 19.

- ^ Coen, Andrew (November 26, 2014). "Port Authority Cross Harbor Freight Could Impact Future Revenues". The Bond Buyer.

- ^ "At first this video might make you want to leave New York. But the end will make you want to stay forever". MoveNY. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015.

- ^ Duggan, Kevin (January 20, 2022). "Hochul unveils more details about Interborough Express in new study". amNewYork. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Interborough Express (IBX)—Feasibility Study and Alternatives Analysis, Interim Report, MTA, January 2022

- ^ Ward, Chris (April 21, 2021). "Needed: A new attack on truck traffic". New York Daily News.

External links

- Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project Several planning documents at this site.

- U.S. Federal Railroad Administration Archived November 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- NYNJ Railroad

- Final Environmental Impact Statement September 2015