Budismo

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

El budismo ( en inglés: /ˈbʊdɪzəm / BUUD - ih - zəm , en inglés : / ˈbːd- / BOOD- ) , [ 1] [2] [3] también conocido como Buddha Dharma y Dharmavinaya , es una religión india [a] y una tradición filosófica basada en las enseñanzas atribuidas a Buda , un maestro errante que vivió en el siglo VI o V a . C. [7] Es la cuarta religión más grande del mundo , [8] [9] con más de 520 millones de seguidores, conocidos como budistas , que comprenden el siete por ciento de la población mundial. [10] [11]

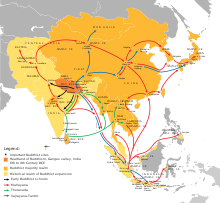

El budismo surgió en la llanura oriental del Ganges como un movimiento śramaṇa en el siglo V a. C. y se extendió gradualmente por gran parte de Asia. Posteriormente ha desempeñado un papel importante en la cultura y la espiritualidad asiáticas, y finalmente se extendió a Occidente en el siglo XX. [12] Según la tradición, el Buda enseñó que el apego o el aferramiento es la "causa" del dukkha ( lit. ' sufrimiento o malestar ' [nota 1] ), pero que existe un camino de desarrollo que conduce al despertar y la liberación total del dukkha . [17] Este camino emplea prácticas de meditación y preceptos éticos arraigados en la no agresión , y el Buda lo considera el Camino Medio entre extremos como el ascetismo o la indulgencia sensual. [18] [19] Las enseñanzas ampliamente observadas incluyen las Cuatro Nobles Verdades , el Noble Camino Óctuple y las doctrinas del origen dependiente , el karma y las tres marcas de la existencia . Otros elementos comúnmente observados incluyen la Triple Joya , la toma de votos monásticos y el cultivo de perfecciones ( pāramitā ). [20]

Las escuelas budistas varían en su interpretación de los caminos hacia la liberación ( mārga ), así como en la importancia relativa y la "canonicidad" asignada a varios textos budistas , y sus enseñanzas y prácticas específicas. [21] [22] Los eruditos generalmente reconocen dos ramas principales existentes del budismo: Theravāda ( lit. ' Escuela de los Ancianos ' ) y Mahāyāna ( lit. ' Gran Vehículo ' ). La tradición Theravada enfatiza el logro del nirvāṇa ( lit. ' extinción ' ) como un medio para trascender el yo individual y terminar el ciclo de muerte y renacimiento ( saṃsāra ), [23] [24] [25] mientras que la tradición Mahayana enfatiza el ideal del Bodhisattva , en el que uno trabaja por la liberación de todos los seres sintientes. Además, Vajrayāna ( lit. ' Vehículo Indestructible ' ), un cuerpo de enseñanzas que incorpora técnicas tántricas esotéricas, puede ser visto como una rama o tradición separada dentro del Mahāyāna. [26]

El canon budista es vasto, con muchas colecciones textuales diferentes en diferentes idiomas (como sánscrito , pali , tibetano y chino ). [27] La rama Theravāda tiene un gran número de seguidores en Sri Lanka , así como en el sudeste asiático, a saber, Myanmar , Tailandia , Laos y Camboya . La rama Mahāyāna, que incluye las tradiciones del este de Asia de Tiantai , Chan , Tierra Pura , Zen , Nichiren y Tendai, se practica predominantemente en Nepal , Bután , China , Malasia , Vietnam , Taiwán , Corea y Japón . El budismo tibetano , una forma de Vajrayāna , se practica en los estados del Himalaya , así como en Mongolia [28] y Kalmykia rusa . [29] El Shingon japonés también preserva la tradición Vajrayana tal como se transmitió a China . Históricamente, hasta principios del segundo milenio , el budismo se practicaba ampliamente en el subcontinente indio antes de declinar allí ; [30] [31] [32] también tuvo un punto de apoyo en cierta medida en otras partes de Asia, a saber , Afganistán , Turkmenistán , Uzbekistán y Tayikistán . [33]

Etimología

Los nombres Buddha Dharma y Bauddha Dharma provienen del sánscrito बुद्ध धर्म y बौद्ध धर्म respectivamente ("doctrina del Iluminado" y "doctrina de los budistas"). Dharmavinaya proviene del sánscrito धर्मविनय , que literalmente significa "doctrinas [y] disciplinas".

El Buda ("el Despierto") fue un Śramaṇa que vivió en el sur de Asia alrededor del siglo VI o V a. C. [34] [35] Los seguidores del budismo, llamados budistas en español, se referían a sí mismos como Sakyan -s o Sakyabhiksu en la antigua India. [36] [37] El erudito budista Donald S. Lopez afirma que también usaban el término Bauddha , [38] aunque el erudito Richard Cohen afirma que ese término solo lo usaban los forasteros para describir a los budistas. [39]

El Buda

Los detalles de la vida de Buda se mencionan en muchos textos budistas primitivos, pero no son uniformes. Su origen social y los detalles de su vida son difíciles de probar, y las fechas precisas son inciertas, aunque el siglo V a. C. parece ser la mejor estimación. [40] [nota 2]

Los primeros textos tienen el nombre de la familia de Buda como "Gautama" (Pali: Gotama), mientras que algunos textos dan a Siddhartha como su apellido. Nació en Lumbini , actual Nepal y creció en Kapilavastu , [nota 3] una ciudad en la llanura del Ganges , cerca de la moderna frontera entre Nepal e India, y pasó su vida en lo que ahora es Bihar [nota 4] y Uttar Pradesh . [48] [40] Algunas leyendas hagiográficas afirman que su padre era un rey llamado Suddhodana , su madre era la reina Maya. [49] Eruditos como Richard Gombrich consideran que esta es una afirmación dudosa porque una combinación de evidencia sugiere que nació en la comunidad Shakya , que estaba gobernada por una pequeña oligarquía o consejo similar a una república donde no había rangos sino que importaba la antigüedad. [50] Algunas de las historias sobre el Buda, su vida, sus enseñanzas y afirmaciones sobre la sociedad en la que creció pueden haber sido inventadas e interpoladas posteriormente en los textos budistas. [51] [52]

En la erudición moderna se discuten varios detalles sobre los antecedentes de Buda. Por ejemplo, los textos budistas afirman que Buda se describió a sí mismo como un kshatriya (clase guerrera), pero Gombrich escribe que se sabe poco sobre su padre y que no hay pruebas de que su padre conociera siquiera el término kshatriya . [53] ( Mahavira , cuyas enseñanzas ayudaron a establecer la antigua religión jainista , también es considerado ksatriya por sus primeros seguidores. [54] )

Según textos antiguos como el Pali Ariyapariyesanā-sutta ("El discurso sobre la noble búsqueda", MN 26) y su paralelo chino en MĀ 204, Gautama se sintió conmovido por el sufrimiento ( dukkha ) de la vida y la muerte, y su repetición sin fin debido al renacimiento . [55] Por lo tanto, se embarcó en una búsqueda para encontrar la liberación del sufrimiento (también conocido como " nirvana "). [56] Los primeros textos y biografías afirman que Gautama estudió primero con dos maestros de meditación, a saber, Āḷāra Kālāma (sánscrito: Arada Kalama) y Uddaka Ramaputta (sánscrito: Udraka Ramaputra), aprendiendo meditación y filosofía, particularmente el logro meditativo de "la esfera de la nada" del primero, y "la esfera de ni percepción ni no percepción" del segundo. [57] [58] [nota 5]

Al encontrar que estas enseñanzas eran insuficientes para alcanzar su objetivo, recurrió a la práctica del ascetismo severo , que incluía un estricto régimen de ayuno y varias formas de control de la respiración . [61] Esto tampoco le permitió alcanzar su objetivo, y entonces recurrió a la práctica meditativa de dhyana . Es famoso que se sentó a meditar bajo un árbol Ficus religiosa —ahora llamado el árbol Bodhi— en la ciudad de Bodh Gaya y alcanzó el "Despertar" ( Bodhi ). [62] [ ¿según quién? ]

Según varios textos antiguos como el Mahāsaccaka-sutta y el Samaññaphala Sutta , al despertar, el Buda obtuvo conocimiento sobre el funcionamiento del karma y sus vidas anteriores, además de lograr el fin de las impurezas mentales ( asavas ), el fin del sufrimiento y el fin del renacimiento en saṃsāra . [61] Este evento también trajo certeza sobre el Camino Medio como el camino correcto de práctica espiritual para terminar con el sufrimiento. [18] [19] Como Buda completamente iluminado , atrajo seguidores y fundó una Sangha (orden monástica). [63] Pasó el resto de su vida enseñando el Dharma que había descubierto, y luego murió, alcanzando el " nirvana final ", a la edad de 80 años en Kushinagar , India. [64] [43] [ ¿según quién? ]

Las enseñanzas del Buda fueron propagadas por sus seguidores, que en los últimos siglos del primer milenio a. C. se convirtieron en varias escuelas de pensamiento budista , cada una con su propia canasta de textos que contenían diferentes interpretaciones y enseñanzas auténticas del Buda; [65] [66] [67] estas con el tiempo evolucionaron en muchas tradiciones de las cuales las más conocidas y difundidas en la era moderna son el budismo Theravada , Mahayana y Vajrayana . [68] [69]

Historia

Raíces históricas

Históricamente, las raíces del budismo se encuentran en el pensamiento religioso de la India de la Edad de Hierro, alrededor de mediados del primer milenio a. C. [70] Este fue un período de gran efervescencia intelectual y cambio sociocultural conocido como la "Segunda urbanización" , marcado por el crecimiento de las ciudades y el comercio, la composición de los Upanishads y el surgimiento histórico de las tradiciones Śramaṇa . [71] [72] [nota 6]

Nuevas ideas se desarrollaron tanto en la tradición védica en forma de los Upanishads, como fuera de la tradición védica a través de los movimientos Śramaṇa. [75] [76] [77] El término Śramaṇa se refiere a varios movimientos religiosos indios paralelos pero separados de la religión védica histórica , incluyendo el budismo, el jainismo y otros como el Ājīvika . [78]

Se sabe que varios movimientos Śramaṇa existieron en la India antes del siglo VI a. C. (pre-Buda, pre- Mahavira ), y estos influyeron tanto en las tradiciones āstika como nāstika de la filosofía india . [79] Según Martin Wilshire, la tradición Śramaṇa evolucionó en la India en dos fases, a saber, las fases Paccekabuddha y Savaka , siendo la primera la tradición del asceta individual y la segunda de los discípulos, y que el budismo y el jainismo finalmente surgieron de estas. [80] Los grupos ascéticos brahmánicos y no brahmánicos compartían y usaban varias ideas similares, [81] pero las tradiciones Śramaṇa también recurrieron a conceptos brahmánicos ya establecidos y raíces filosóficas, afirma Wiltshire, para formular sus propias doctrinas. [79] [82] Se pueden encontrar motivos brahmánicos en los textos budistas más antiguos, utilizándolos para introducir y explicar ideas budistas. [83] Por ejemplo, antes de los desarrollos budistas, la tradición brahmánica internalizó y reinterpretó de diversas maneras los tres fuegos sacrificiales védicos como conceptos tales como Verdad, Rito, Tranquilidad o Restricción. [84] Los textos budistas también se refieren a los tres fuegos sacrificiales védicos, reinterpretándolos y explicándolos como conducta ética. [85]

Las religiones Śramaṇa desafiaron y rompieron con la tradición brahmánica en supuestos centrales como Atman (alma, yo), Brahman , la naturaleza de la vida después de la muerte, y rechazaron la autoridad de los Vedas y los Upanishads . [86] [87] [88] El budismo fue una de varias religiones indias que hicieron lo mismo. [88]

Las primeras posturas budistas de la tradición Theravada no habían establecido ninguna deidad, pero eran epistemológicamente cautelosas en lugar de directamente ateas . Las tradiciones budistas posteriores estuvieron más influenciadas por la crítica de las deidades dentro del hinduismo y, por lo tanto, más comprometidas con una postura fuertemente atea. Estos desarrollos fueron históricos y epistemológicos como se documenta en los versos del Bodhicaryāvatāra de Śāntideva , y complementados con referencias a suttas y jātakas del canon Pali . [89]

Budismo indio

La historia del budismo indio puede dividirse en cinco períodos: [90] Budismo temprano (a veces llamado budismo presectario ), Budismo Nikaya o budismo sectario (el período de las primeras escuelas budistas), Budismo Mahayana temprano , Mahayana tardío y la era Vajrayana o la "Era Tántrica".

Budismo presectario

Según Lambert Schmithausen, el budismo presectario es "el período canónico anterior al desarrollo de diferentes escuelas con sus diferentes posiciones". [91]

Los primeros textos budistas incluyen los cuatro Nikāyas pali principales [nota 7] (y sus Agamas paralelos que se encuentran en el canon chino) junto con el cuerpo principal de reglas monásticas, que sobreviven en las diversas versiones del patimokkha . [92] [93] [94] Sin embargo, estos textos fueron revisados con el tiempo y no está claro qué constituye la capa más antigua de enseñanzas budistas. Un método para obtener información sobre el núcleo más antiguo del budismo es comparar las versiones existentes más antiguas del Canon pali de Theravadin y otros textos. [nota 8] La confiabilidad de las fuentes tempranas y la posibilidad de extraer un núcleo de enseñanzas más antiguas es un tema de disputa. [97] Según Vetter, persisten inconsistencias y se deben aplicar otros métodos para resolverlas. [95] [nota 9]

Según Schmithausen, se pueden distinguir tres posiciones sostenidas por los estudiosos del budismo: [103]

- "Se hace hincapié en la homogeneidad fundamental y la autenticidad sustancial de al menos una parte considerable de los materiales nicáicos". Entre los defensores de esta postura se encuentran AK Warder [nota 10] y Richard Gombrich . [105] [nota 11]

- "Escepticismo respecto de la posibilidad de recuperar la doctrina del budismo primitivo". Ronald Davidson es un defensor de esta postura. [nota 12]

- "Un optimismo cauteloso a este respecto". Entre los defensores de esta posición se encuentran J. W. de Jong, [107] [nota 13] Johannes Bronkhorst [nota 14] y Donald Lopez. [nota 15]

Las enseñanzas fundamentales

Según Mitchell, ciertas enseñanzas básicas aparecen en muchos lugares a lo largo de los textos tempranos, lo que ha llevado a la mayoría de los estudiosos a concluir que Gautama Buda debe haber enseñado algo similar a las Cuatro Nobles Verdades , el Noble Óctuple Sendero , el Nirvana , las tres marcas de la existencia , los cinco agregados , el origen dependiente , el karma y el renacimiento . [109]

Según N. Ross Reat, todas estas doctrinas son compartidas por los textos Theravada Pali y el Śālistamba Sūtra de la escuela Mahasamghika . [110] Un estudio reciente de Bhikkhu Analayo concluye que el Theravada Majjhima Nikaya y el Sarvastivada Madhyama Agama contienen en su mayoría las mismas doctrinas principales. [111] Richard Salomon , en su estudio de los textos de Gandharan (que son los manuscritos más antiguos que contienen discursos tempranos), ha confirmado que sus enseñanzas son "consistentes con el budismo no Mahayana, que sobrevive hoy en la escuela Theravada de Sri Lanka y el sudeste asiático, pero que en la antigüedad estaba representada por dieciocho escuelas separadas". [112]

Sin embargo, algunos eruditos sostienen que el análisis crítico revela discrepancias entre las diversas doctrinas encontradas en estos textos tempranos, que apuntan a posibilidades alternativas para el budismo temprano. [113] [114] [115] Se ha cuestionado la autenticidad de ciertas enseñanzas y doctrinas. Por ejemplo, algunos eruditos piensan que el karma no era central para la enseñanza del Buda histórico, mientras que otros no están de acuerdo con esta posición. [116] [117] Del mismo modo, existe un desacuerdo académico sobre si la introspección se consideraba liberadora en el budismo temprano o si fue una adición posterior a la práctica de los cuatro jhānas . [98] [118] [119] Eruditos como Bronkhorst también piensan que las cuatro nobles verdades pueden no haber sido formuladas en el budismo más temprano, y no sirvieron en el budismo más temprano como una descripción de la "introspección liberadora". [120] Según Vetter, la descripción del camino budista puede haber sido inicialmente tan simple como el término "el camino medio". [99] Con el tiempo, esta breve descripción se fue elaborando, dando como resultado la descripción del óctuple sendero. [99]

La era Ashoka y las primeras escuelas

Según numerosas escrituras budistas, poco después del parinirvāṇa (del sánscrito: "extinción suprema") de Gautama Buda, se celebró el primer concilio budista para recitar colectivamente las enseñanzas y garantizar que no se produjeran errores en la transmisión oral. Muchos eruditos modernos cuestionan la historicidad de este evento. [121] Sin embargo, Richard Gombrich afirma que las recitaciones de las enseñanzas del Buda en asambleas monásticas probablemente comenzaron durante la vida de Buda, y cumplieron una función similar de codificación de las enseñanzas. [122]

El llamado Segundo Concilio Budista resultó en el primer cisma en la Sangha . Los eruditos modernos creen que esto probablemente fue causado cuando un grupo de reformistas llamados Sthaviras ("ancianos") buscaron modificar el Vinaya (regla monástica), y esto causó una división con los conservadores que rechazaron este cambio, ellos fueron llamados Mahāsāṃghikas . [123] [124] Si bien la mayoría de los eruditos aceptan que esto sucedió en algún momento, no hay acuerdo sobre la datación, especialmente si data de antes o después del reinado de Ashoka. [125]

El budismo se extendió lentamente por toda la India hasta la época del emperador maurya Ashoka (304-232 a. C.), que fue un defensor público de la religión. El apoyo de Ashoka y sus descendientes condujo a la construcción de más stūpas (como las de Sanchi y Bharhut ), templos (como el templo Mahabodhi ) y a su expansión por todo el Imperio maurya y a tierras vecinas como Asia Central y la isla de Sri Lanka .

Durante y después del período Maurya (322-180 a. C.), la comunidad Sthavira dio origen a varias escuelas, una de las cuales fue la escuela Theravada , que tendía a congregarse en el sur, y otra, la escuela Sarvāstivāda , que se encontraba principalmente en el norte de la India. Del mismo modo, los grupos Mahāsāṃghika también terminaron dividiéndose en diferentes Sanghas. Originalmente, estos cismas fueron causados por disputas sobre los códigos disciplinarios monásticos de varias fraternidades, pero con el tiempo, alrededor del año 100 d. C., si no antes, los cismas también fueron causados por desacuerdos doctrinales. [126]

Después de (o antes de) los cismas, cada Saṅgha comenzó a acumular su propia versión del Tripiṭaka (triple canasta de textos). [67] [127] En su Tripiṭaka, cada escuela incluía los Suttas del Buda, una canasta Vinaya (código disciplinario) y algunas escuelas también añadieron una canasta Abhidharma que eran textos sobre clasificación escolástica detallada, resumen e interpretación de los Suttas. [67] [128] Los detalles de la doctrina en los Abhidharmas de varias escuelas budistas difieren significativamente, y estos fueron compuestos a partir del siglo III a. C. y durante el primer milenio d. C. [129] [130] [131]

Expansión post-Ashokan

Según los edictos de Aśoka , el emperador Maurya envió emisarios a varios países al oeste de la India para difundir el "Dharma", en particular en las provincias orientales del vecino Imperio seléucida , e incluso más lejos, a los reinos helenísticos del Mediterráneo. Existe un desacuerdo entre los eruditos sobre si estos emisarios estaban acompañados o no por misioneros budistas. [132]

En Asia central y occidental, la influencia budista creció, a través de los monarcas budistas de habla griega y las antiguas rutas comerciales asiáticas, un fenómeno conocido como grecobudismo . Un ejemplo de esto se evidencia en los registros budistas chinos y pali, como Milindapanha y el arte grecobudista de Gandhāra . El Milindapanha describe una conversación entre un monje budista y el rey griego del siglo II a. C. Menandro , después de la cual Menandro abdica y él mismo entra en la vida monástica en busca del nirvana. [133] [134] Algunos eruditos han cuestionado la versión de Milindapanha , expresando dudas sobre si Menandro era budista o simplemente tenía una disposición favorable hacia los monjes budistas. [135]

El imperio Kushan (30-375 d. C.) llegó a controlar el comercio de la Ruta de la Seda a través de Asia Central y del Sur, lo que los llevó a interactuar con el budismo gandhariano y las instituciones budistas de estas regiones. Los Kushan patrocinaron el budismo en sus tierras, y se construyeron o renovaron muchos centros budistas (la escuela Sarvastivada fue particularmente favorecida), especialmente por el emperador Kanishka (128-151 d. C.). [136] [137] El apoyo de los Kushan ayudó a que el budismo se expandiera hasta convertirse en una religión mundial a través de sus rutas comerciales. [138] El budismo se extendió a Khotan , la cuenca del Tarim y China, y finalmente a otras partes del lejano oriente. [137] Algunos de los primeros documentos escritos de la fe budista son los textos budistas gandharianos , que datan de aproximadamente el siglo I d. C. y están relacionados con la escuela Dharmaguptaka . [139] [140] [141]

La conquista islámica de la meseta iraní en el siglo VII, seguida por las conquistas musulmanas de Afganistán y el posterior establecimiento del reino Ghaznavid con el Islam como religión estatal en Asia Central entre los siglos X y XII, llevaron a la decadencia y desaparición del budismo en la mayoría de estas regiones. [142]

Budismo Mahāyāna

Los orígenes del budismo Mahāyāna ("Gran Vehículo") no se comprenden bien y existen varias teorías que compiten entre sí sobre cómo y dónde surgió este movimiento. Algunas teorías incluyen la idea de que comenzó como varios grupos que veneraban ciertos textos o que surgió como un movimiento ascético estricto en el bosque. [143]

Las primeras obras Mahāyāna fueron escritas en algún momento entre el siglo I a. C. y el siglo II d. C. [144] [143] Gran parte de la evidencia existente temprana sobre los orígenes del Mahāyāna proviene de las primeras traducciones chinas de los textos Mahāyāna, principalmente las de Lokakṣema (siglo II d. C.). [nota 16] Algunos eruditos han considerado tradicionalmente que los primeros sūtras Mahāyāna incluyen las primeras versiones de la serie Prajnaparamita , junto con textos relacionados con Akṣobhya , que probablemente fueron compuestos en el siglo I a. C. en el sur de la India. [146] [nota 17]

No hay evidencia de que Mahāyāna alguna vez se refiriera a una escuela formal separada o secta del budismo, con un código monástico separado (Vinaya), sino más bien que existía como un cierto conjunto de ideales, y doctrinas posteriores, para los bodhisattvas. [148] [149] Los registros escritos por monjes chinos que visitaron la India indican que tanto monjes Mahāyāna como no Mahāyāna podían encontrarse en los mismos monasterios, con la diferencia de que los monjes Mahāyāna adoraban figuras de Bodhisattvas, mientras que los monjes no Mahayana no lo hacían. [150]

Al principio, el Mahāyāna parece haber seguido siendo un pequeño movimiento minoritario que se encontraba en tensión con otros grupos budistas y luchaba por lograr una mayor aceptación. [151] Sin embargo, durante los siglos V y VI d. C., parece haber habido un rápido crecimiento del budismo Mahāyāna, como lo demuestra un gran aumento de la evidencia epigráfica y manuscrita en este período. Sin embargo, siguió siendo una minoría en comparación con otras escuelas budistas. [152]

Las instituciones budistas Mahāyāna continuaron creciendo en influencia durante los siglos siguientes, con grandes complejos universitarios monásticos como Nalanda (fundado por el emperador Gupta del siglo V d.C., Kumaragupta I ) y Vikramashila (fundado bajo Dharmapala c. 783 a 820) que se volvieron bastante poderosos e influyentes. Durante este período del Mahāyāna tardío, se desarrollaron cuatro tipos principales de pensamiento: Mādhyamaka, Yogācāra, naturaleza búdica ( Tathāgatagarbha ) y la tradición epistemológica de Dignaga y Dharmakirti . [153] Según Dan Lusthaus , Mādhyamaka y Yogācāra tienen mucho en común, y la similitud proviene del budismo temprano. [154]

Budismo indio tardío y tantra

Durante el período Gupta (siglos IV-VI) y el imperio de Harṣavardana ( c. 590-647 d. C.), el budismo continuó siendo influyente en la India, y las grandes instituciones de aprendizaje budista como las universidades de Nalanda y Valabahi estaban en su apogeo. [155] El budismo también floreció bajo el apoyo del Imperio Pāla (siglos VIII-XII). Bajo los Gupta y los Palas, el budismo tántrico o Vajrayana se desarrolló y alcanzó prominencia. Promovió nuevas prácticas como el uso de mantras , dharanis , mudras , mandalas y la visualización de deidades y budas y desarrolló una nueva clase de literatura, los tantras budistas . Esta nueva forma esotérica de budismo se remonta a grupos de magos yoguis errantes llamados mahasiddhas . [156] [157]

Varios estudiosos han abordado la cuestión de los orígenes del Vajrayana primitivo. David Seyfort Ruegg ha sugerido que el tantra budista empleaba diversos elementos de un "sustrato religioso panindio" que no es específicamente budista, shaiva o vaishnava. [158]

Según el indólogo Alexis Sanderson , varias clases de literatura vajrayana se desarrollaron como resultado de las cortes reales que patrocinaron tanto el budismo como el saivismo . Sanderson ha argumentado que se puede demostrar que los tantras budistas han tomado prestadas prácticas, términos, rituales y más de los tantras Shaiva. Sostiene que los textos budistas incluso copiaron directamente varios tantras Shaiva, especialmente los tantras Bhairava Vidyapitha. [159] [160] Mientras tanto, Ronald M. Davidson sostiene que las afirmaciones de Sanderson sobre la influencia directa de los textos Shaiva Vidyapitha son problemáticas porque "la cronología de los tantras Vidyapitha no está de ninguna manera tan bien establecida" [161] y que la tradición Shaiva también se apropió de deidades, textos y tradiciones no hindúes. Por lo tanto, si bien "no puede haber duda de que los tantras budistas fueron fuertemente influenciados por Kapalika y otros movimientos Saiva", argumenta Davidson, "la influencia fue aparentemente mutua". [162]

Ya durante esta era posterior, el budismo estaba perdiendo el apoyo estatal en otras regiones de la India, incluidas las tierras de los Karkotas , los Pratiharas , los Rashtrakutas , los Pandyas y los Pallavas . Esta pérdida de apoyo a favor de las religiones hindúes como el vaishnavismo y el shivaísmo , es el comienzo del largo y complejo período de la decadencia del budismo en el subcontinente indio . [163] Las invasiones y conquistas islámicas de la India (siglos X al XII), dañaron y destruyeron aún más muchas instituciones budistas, lo que llevó a su eventual casi desaparición de la India en el siglo XIII. [164]

Se extendió al este y sudeste de Asia

Se cree que la transmisión del budismo a China a través de la Ruta de la Seda comenzó a fines del siglo II o del siglo I d. C., aunque todas las fuentes literarias están abiertas a discusión. [165] [nota 18] Los primeros esfuerzos de traducción documentados por monjes budistas extranjeros en China fueron en el siglo II d. C., probablemente como consecuencia de la expansión del Imperio Kushan en el territorio chino de la cuenca del Tarim . [167]

Los primeros textos budistas documentados traducidos al chino son los del parto An Shigao (148-180 d. C.). [168] Los primeros textos escriturales Mahāyāna conocidos son traducciones al chino realizadas por el monje Kushan Lokakṣema en Luoyang , entre 178 y 189 d. C. [169] Desde China, el budismo se introdujo en sus vecinos Corea (siglo IV), Japón (siglos VI-VII) y Vietnam ( c. siglos I -II). [170] [171]

Durante la dinastía china Tang (618-907), el budismo esotérico chino se introdujo desde la India y el budismo Chan (zen) se convirtió en una religión importante. [172] [173] El Chan continuó creciendo en la dinastía Song (960-1279) y fue durante esta era que influyó fuertemente en el budismo coreano y el budismo japonés. [174] El budismo de la Tierra Pura también se hizo popular durante este período y a menudo se practicaba junto con el Chan. [175] También fue durante la dinastía Song que se imprimió todo el canon chino utilizando más de 130.000 bloques de impresión de madera. [176]

Durante el período indio del budismo esotérico (a partir del siglo VIII), el budismo se extendió desde la India hasta el Tíbet y Mongolia . Johannes Bronkhorst afirma que la forma esotérica era atractiva porque permitía tanto una comunidad monástica aislada como los ritos y rituales sociales importantes para los laicos y los reyes para el mantenimiento de un estado político durante la sucesión y las guerras para resistir la invasión. [177] Durante la Edad Media, el budismo decayó lentamente en la India, [178] mientras que desapareció de Persia y Asia Central cuando el Islam se convirtió en la religión del estado. [179] [180]

La escuela Theravada llegó a Sri Lanka en algún momento del siglo III a. C. Sri Lanka se convirtió en una base para su posterior expansión al sudeste asiático después del siglo V d. C. ( Myanmar , Malasia , Indonesia , Tailandia , Camboya y la costa de Vietnam ). [181] [182] El budismo Theravada fue la religión dominante en Birmania durante el Reino Mon Hanthawaddy (1287-1552). [183] También se volvió dominante en el Imperio Jemer durante los siglos XIII y XIV y en el Reino Sukhothai tailandés durante el reinado de Ram Khamhaeng (1237/1247-1298). [184] [185]

Visión del mundo

El término "budismo" es un neologismo occidental, comúnmente (y "bastante toscamente" según Donald S. Lopez Jr. ) usado como traducción del Dharma del Buda , fójiào en chino, bukkyō en japonés, nang pa sangs rgyas pa'i chos en tibetano, buddhadharma en sánscrito, buddhaśāsana en pali. [186]

Cuatro nobles verdades

Las Cuatro Nobles Verdades, o las verdades de los Nobles , [187] enseñadas en el budismo son:

- Dukkha ("no estar a gusto", "sufrir") es una característica innata del ciclo perpetuo ( samsara , lit. ' vagar ' ) de aferrarse a las cosas, ideas y hábitos.

- Samudaya (origen, surgimiento, combinación; "causa"): dukkha es causado por taṇhā ("anhelo", "deseo" o "apego", literalmente "sed")

- Nirodha (cese, finalización, confinamiento): dukkha puede terminar o ser contenido mediante el confinamiento o el abandono de taṇhā.

- Marga (camino): el camino que conduce al confinamiento de taṇhā y dukkha , clásicamente el Noble Óctuple Sendero , pero a veces otros caminos hacia la liberación.

Tres marcas de existencia

La mayoría de las escuelas del budismo enseñan tres marcas de existencia : [188]

- Dukkha : malestar, sufrimiento

- Anicca : impermanencia

- Anattā : no-yo; los seres vivos no tienen alma o esencia inmanente permanente [189] [190] [191]

El budismo enseña que la idea de que algo es permanente o que hay un yo en algún ser es ignorancia o percepción errónea ( avijjā ), y que esta es la fuente primaria del apego y del dukkha. [192] [193] [194]

Algunas escuelas describen cuatro características o “cuatro sellos del Dharma”, añadiendo a lo anterior:

- El nirvana es paz ( śānta/śānti ) [195] [196]

El ciclo del renacimiento

Samsara

Saṃsāra significa "errante" o "mundo", con la connotación de cambio cíclico y tortuoso. [197] [198] Se refiere a la teoría del renacimiento y la "ciclicidad de toda vida, materia, existencia", un supuesto fundamental del budismo, como en todas las principales religiones indias. [198] [199] El samsara en el budismo se considera dukkha , insatisfactorio y doloroso, [200] perpetuado por el deseo y la avidya (ignorancia), y el karma resultante . [198] [201] [202] La liberación de este ciclo de existencia, el nirvana , ha sido el fundamento y la justificación histórica más importante del budismo. [203] [204]

Los textos budistas afirman que el renacimiento puede ocurrir en seis reinos de existencia, a saber, tres reinos buenos (celestial, semidiós, humano) y tres reinos malos (animal, fantasmas hambrientos, infernal). [nota 19] El samsara termina si una persona alcanza el nirvana , la "extinción" de las aflicciones a través de la comprensión de la impermanencia y el " no-yo ". [206] [207] [208]

Renacimiento

El renacimiento se refiere a un proceso mediante el cual los seres pasan por una sucesión de vidas como una de las muchas formas posibles de vida sensible , cada una de las cuales va desde la concepción hasta la muerte. [209] En el pensamiento budista, este renacimiento no implica un alma ni ninguna sustancia fija. Esto se debe a que la doctrina budista de anattā (sánscrito: anātman , doctrina de la no existencia de un yo) rechaza los conceptos de un yo permanente o un alma inmutable y eterna que se encuentran en otras religiones. [210] [211]

Las tradiciones budistas tradicionalmente han estado en desacuerdo sobre qué es lo que renace en una persona, así como con qué rapidez ocurre el renacimiento después de la muerte. [212] [213] Algunas tradiciones budistas afirman que la doctrina de la "ausencia de yo" significa que no hay un yo duradero, sino que hay una personalidad avacya (inexpresable) ( pudgala ) que migra de una vida a otra. [212] La mayoría de las tradiciones budistas, en cambio, afirman que vijñāna (la conciencia de una persona), aunque evoluciona, existe como un continuo y es la base mecanicista de lo que experimenta el proceso de renacimiento. [214] [212] La calidad del renacimiento de uno depende del mérito o demérito obtenido por el karma de uno (es decir, las acciones), así como del acumulado en nombre de uno por un miembro de la familia. [nota 20] El budismo también desarrolló una cosmología compleja para explicar los diversos reinos o planos del renacimiento. [200]

Karma

En el budismo , el karma (del sánscrito : «acción, trabajo») impulsa el saṃsāra , el ciclo interminable de sufrimiento y renacimiento de cada ser. Las buenas acciones hábiles (en pali: kusala ) y las malas acciones torpes (en pali: akusala ) producen «semillas» en el receptáculo inconsciente ( ālaya ) que maduran más tarde, ya sea en esta vida o en un renacimiento posterior . [216] [217] La existencia del karma es una creencia central en el budismo, como en todas las principales religiones indias, y no implica ni fatalismo ni que todo lo que le sucede a una persona sea causado por el karma. [218] (Las enfermedades y el sufrimiento inducidos por las acciones disruptivas de otras personas son ejemplos de sufrimiento no kármico. [218] )

Un aspecto central de la teoría budista del karma es que la intención ( cetanā ) importa y es esencial para producir una consecuencia o phala "fruto" o vipāka "resultado". [219] El énfasis en la intención en el budismo marca una diferencia con la teoría kármica del jainismo, donde el karma se acumula con o sin intención. [220] [221] El énfasis en la intención también se encuentra en el hinduismo, y el budismo puede haber influido en las teorías del karma del hinduismo. [222]

En el budismo, el karma bueno o malo se acumula incluso si no hay acción física, y el solo hecho de tener malos o buenos pensamientos crea semillas kármicas; por lo tanto, las acciones del cuerpo, el habla o la mente conducen a semillas kármicas. [218] En las tradiciones budistas, los aspectos de la vida afectados por la ley del karma en los nacimientos pasados y actuales de un ser incluyen la forma de renacimiento, el reino de renacimiento, la clase social, el carácter y las circunstancias principales de la vida. [218] [223] [224] Según la teoría, opera como las leyes de la física, sin intervención externa, en cada ser en los seis reinos de la existencia, incluidos los seres humanos y los dioses. [218] [225]

Un aspecto notable de la teoría del karma en el budismo moderno es la transferencia de méritos. [226] [227] Una persona acumula méritos no solo a través de las intenciones y la vida ética, sino que también puede ganar méritos de otros intercambiando bienes y servicios, como a través de dāna (caridad a monjes o monjas). [228] La teoría también establece que una persona puede transferir su propio buen karma a familiares y antepasados vivos. [227]

Esta idea budista puede tener raíces en las creencias de intercambio quid-pro-quo de los rituales védicos hindúes. [229] El concepto de "transferencia de mérito de karma" ha sido controvertido, no aceptado en las tradiciones posteriores del jainismo y el hinduismo, a diferencia del budismo, donde fue adoptado en la antigüedad y sigue siendo una práctica común. [226] Según Bruce Reichenbach, la idea de "transferencia de mérito" generalmente estaba ausente en el budismo temprano y puede haber surgido con el surgimiento del budismo Mahayana; agrega que si bien las principales escuelas hindúes como Yoga, Advaita Vedanta y otras no creen en la transferencia de mérito, algunas tradiciones hindúes bhakti adoptaron más tarde la idea al igual que el budismo. [230]

Liberación

.jpg/440px-050_Mucilinda_with_his_Wives_around_the_Buddha_(32999346203).jpg)

El cese de los kleshas y el logro del nirvana ( nibbāna ), con el que termina el ciclo de renacimientos, ha sido el objetivo primario y soteriológico del camino budista para la vida monástica desde el tiempo del Buda. [231] [232] [233] El término "camino" se suele tomar como el Noble Óctuple Sendero , pero también se pueden encontrar otras versiones de "el camino" en los Nikayas. [nota 21] En algunos pasajes del Canon Pali, se hace una distinción entre el conocimiento o visión correcta ( sammā-ñāṇa ), y la liberación o liberación correcta ( sammā-vimutti ), como los medios para alcanzar el cese y la liberación. [235] [236]

Nirvana significa literalmente "apagarse, apagarse, extinguirse". [237] [238] En los primeros textos budistas, es el estado de restricción y autocontrol lo que conduce al "apagado" y al final de los ciclos de sufrimientos asociados con los renacimientos y las redeaths. [99] [239] [240] Muchos textos budistas posteriores describen el nirvana como idéntico a anatta con completo "vacío, nada". [241] [242] [243] [nota 22] En algunos textos, el estado se describe con mayor detalle, como pasar por la puerta del vacío ( sunyata ) -dándose cuenta de que no hay alma o yo en ningún ser vivo, luego pasando por la puerta de la ausencia de signos ( animitta ) -dándose cuenta de que el nirvana no puede ser percibido, y finalmente pasando por la puerta de la ausencia de deseos ( apranihita ) -dándose cuenta de que el nirvana es el estado de ni siquiera desear el nirvana. [232] [245] [nota 23]

El estado de nirvana ha sido descrito en textos budistas en parte de una manera similar a otras religiones indias, como el estado de liberación completa, iluminación, máxima felicidad, dicha, intrepidez, libertad, permanencia, origen no dependiente, insondable e indescriptible. [247] [248] También ha sido descrito en parte de manera diferente, como un estado de liberación espiritual marcado por el "vacío" y la realización del no-yo . [249] [250] [251] [nota 24]

Si bien el budismo considera la liberación del saṃsāra como el objetivo espiritual último, en la práctica tradicional, el objetivo principal de una gran mayoría de budistas laicos ha sido buscar y acumular méritos a través de buenas acciones, donaciones a monjes y diversos rituales budistas para obtener mejores renacimientos en lugar del nirvana. [254] [255] [nota 25]

Surgimiento dependiente

Pratityasamutpada , también llamada "surgimiento dependiente u origen dependiente", es la teoría budista para explicar la naturaleza y las relaciones del ser, el devenir, la existencia y la realidad última. El budismo afirma que no hay nada independiente, excepto el estado de nirvana. [258] Todos los estados físicos y mentales dependen de otros estados preexistentes y surgen de ellos, y a su vez de ellos surgen otros estados dependientes mientras cesan. [259]

Los 'surgimientos dependientes' tienen un condicionamiento causal, y por lo tanto Pratityasamutpada es la creencia budista de que la causalidad es la base de la ontología , no un Dios creador ni el concepto ontológico védico llamado Ser universal ( Brahman ) ni ningún otro 'principio creativo trascendente'. [260] [261] Sin embargo, el pensamiento budista no entiende la causalidad en términos de la mecánica newtoniana; más bien la entiende como surgimiento condicionado. [262] [263] En el budismo, el surgimiento dependiente se refiere a las condiciones creadas por una pluralidad de causas que necesariamente co-originan un fenómeno dentro y a través de las vidas, como el karma en una vida que crea condiciones que conducen al renacimiento en uno de los reinos de la existencia para otra vida. [264] [265] [266]

El budismo aplica la teoría del surgimiento dependiente para explicar el origen de los ciclos infinitos de dukkha y renacimiento, a través de los Doce Nidānas o "doce vínculos". Afirma que debido a que existe Avidyā (ignorancia), existen Saṃskāras (formaciones kármicas); debido a que existen Saṃskāras, existe Vijñāna (conciencia); y de manera similar vincula Nāmarūpa (el cuerpo sintiente), Ṣaḍāyatana (nuestros seis sentidos), Sparśa (estimulación sensorial), Vedanā (sensación), Taṇhā (anhelo), Upādāna (aferramiento), Bhava (llegar a ser), Jāti (nacimiento) y Jarāmaraṇa (vejez, muerte, pena y dolor). [267] [268] Al romper los vínculos tortuosos de los Doce Nidanas, el budismo afirma que se puede alcanzar la liberación de estos ciclos interminables de renacimiento y dukkha. [269]

No-Yo y Vacuidad

| Los Cinco Agregados ( pañca khandha ) según el Canon Pali . | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| → ← ← |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fuente: MN 109 (Thanissaro, 2001) | detalles del diagrama | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Una doctrina relacionada en el budismo es la de anattā (Pali) o anātman (Sánscrito). Es la visión de que no hay un yo, alma o esencia inmutable y permanente en los fenómenos. [270] El Buda y los filósofos budistas que lo siguen, como Vasubandhu y Buddhaghosa, generalmente defienden esta visión analizando a la persona a través del esquema de los cinco agregados , y luego intentando demostrar que ninguno de estos cinco componentes de la personalidad puede ser permanente o absoluto. [271] Esto se puede ver en discursos budistas como el Anattalakkhana Sutta .

El concepto de "vacío" o "vacuidad" (Skt : Śūnyatā , Pali: Suññatā) tiene muchas interpretaciones diferentes en los distintos budismos. En el budismo primitivo, se afirmaba comúnmente que los cinco agregados son vacíos ( rittaka ), huecos ( tucchaka ) y sin núcleo ( asāraka ), como se afirma en el Pheṇapiṇḍūpama Sutta (SN 22:95). [272] De manera similar, en el budismo Theravada, a menudo significa que los cinco agregados están vacíos de un Ser. [273]

La vacuidad es un concepto central en el budismo Mahāyāna, especialmente en la escuela Madhyamaka de Nagarjuna y en los sutras Prajñāpāramitā . En la filosofía Madhyamaka, la vacuidad es la visión que sostiene que todos los fenómenos carecen de svabhava (literalmente, "naturaleza propia" o "naturaleza propia") y, por lo tanto, carecen de una esencia subyacente y, por lo tanto, están "vacíos" de ser independientes. [ ejemplo necesario ] Esta doctrina pretendía refutar las teorías heterodoxas de svabhava que circulaban en ese momento. [274]

Las tres joyas

Todas las formas de budismo veneran y toman refugio espiritual en las "tres joyas" ( triratna ): Buda, Dharma y Sangha. [275]

Buda

Si bien todas las variedades del budismo veneran a "Buda" y la "budeidad", tienen diferentes puntos de vista sobre lo que significan. Independientemente de su interpretación, el concepto de Buda es central para todas las formas de budismo.

En el budismo Theravada, un Buda es alguien que ha despertado gracias a sus propios esfuerzos y perspicacia. Ha puesto fin a su ciclo de renacimientos y ha acabado con todos los estados mentales nocivos que conducen a malas acciones y, por lo tanto, se ha perfeccionado moralmente. [276] Aunque está sujeto a las limitaciones del cuerpo humano en ciertos aspectos (por ejemplo, en los primeros textos, el Buda sufre de dolores de espalda), se dice que un Buda es "profundo, inmensurable, difícil de sondear como lo es el gran océano", y también tiene inmensos poderes psíquicos ( abhijñā ). [277] El Theravada generalmente ve a Gautama Buda (el Buda histórico Sakyamuni) como el único Buda de la era actual.

Mientras tanto, el budismo Mahāyāna tiene una cosmología enormemente expandida , con varios Budas y otros seres sagrados ( aryas ) que residen en diferentes reinos. Los textos Mahāyāna no solo veneran a numerosos Budas además de Shakyamuni , como Amitabha y Vairocana , sino que también los ven como seres trascendentales o supramundanos ( lokuttara ). [278] El budismo Mahāyāna sostiene que estos otros Budas en otros reinos pueden ser contactados y pueden beneficiar a los seres en este mundo. [279] En Mahāyāna, un Buda es una especie de "rey espiritual", un "protector de todas las criaturas" con una vida de incontables eones de duración, en lugar de solo un maestro humano que ha trascendido el mundo después de la muerte. [280] La vida y muerte de Shakyamuni en la tierra se entiende entonces habitualmente como una "mera aparición" o "una manifestación hábilmente proyectada en la vida terrenal por un ser trascendente largamente iluminado, que todavía está disponible para enseñar a los fieles a través de experiencias visionarias". [280] [281]

Dharma

La segunda de las tres joyas es el “Dharma” (Pali: Dhamma), que en el budismo se refiere a la enseñanza del Buda, que incluye todas las ideas principales descritas anteriormente. Si bien esta enseñanza refleja la verdadera naturaleza de la realidad, no es una creencia a la que aferrarse, sino una enseñanza pragmática que se debe poner en práctica. Se la compara con una balsa que es “para cruzar” (al nirvana), no para aferrarse a ella. [282] También se refiere a la ley universal y al orden cósmico que esa enseñanza revela y en el que se basa. [283] Es un principio eterno que se aplica a todos los seres y mundos. En ese sentido, es también la verdad y realidad última sobre el universo, es por tanto “la forma en que las cosas realmente son”.

Sangha

La tercera "joya" en la que se refugian los budistas es la "Sangha", que se refiere a la comunidad monástica de monjes y monjas que siguen la disciplina monástica de Gautama Buda, que fue "diseñada para dar forma a la Sangha como una comunidad ideal, con las condiciones óptimas para el crecimiento espiritual". [284] La Sangha está formada por aquellos que han elegido seguir el modo de vida ideal del Buda, que es el de la renuncia monástica célibe con posesiones materiales mínimas (como un cuenco de limosnas y túnicas). [285]

La Sangha es considerada importante porque preserva y transmite el Dharma del Buda. Como afirma Gethin, “la Sangha vive la enseñanza, preserva la enseñanza como Escrituras y enseña a la comunidad en general. Sin la Sangha no hay Budismo”. [286] La Sangha también actúa como un “campo de mérito” para los laicos, permitiéndoles hacer mérito espiritual o bondad mediante donaciones a la Sangha y apoyo. A cambio, ellos cumplen con su deber de preservar y difundir el Dharma en todas partes para el bien del mundo. [287]

También existe una definición separada de Sangha, que se refiere a aquellos que han alcanzado cualquier etapa del despertar , sean o no monásticos. Esta sangha se llama āryasaṅgha "Sangha noble". [288] Todas las formas de budismo generalmente veneran a estos āryas (Pali: ariya , "nobles" o "santos") que son seres espiritualmente alcanzados. Los aryas han alcanzado los frutos del camino budista. [289] Convertirse en un arya es una meta en la mayoría de las formas de budismo. El āryasaṅgha incluye seres sagrados como bodhisattvas , arhats y personas que entran en la corriente.

Otras visiones clave del Mahāyāna

El budismo Mahāyāna también se diferencia del Theravada y de otras escuelas del budismo temprano en la promoción de varias doctrinas únicas que están contenidas en los sutras Mahāyāna y tratados filosóficos.

Una de ellas es la interpretación única de la vacuidad y el origen dependiente que se encuentra en la escuela Madhyamaka. Otra doctrina muy influyente para el Mahāyāna es la principal visión filosófica de la escuela Yogācāra , denominada de diversas formas Vijñaptimātratā-vāda ("la doctrina de que sólo hay ideas" o "impresiones mentales") o Vijñānavāda ("la doctrina de la conciencia"). Según Mark Siderits, lo que los pensadores clásicos de Yogācāra como Vasubandhu tenían en mente es que sólo somos conscientes de imágenes o impresiones mentales, que pueden aparecer como objetos externos, pero "en realidad no existe tal cosa fuera de la mente". [290] Hay varias interpretaciones de esta teoría principal; muchos estudiosos la ven como un tipo de idealismo, otros como una especie de fenomenología. [291]

Otro concepto muy influyente y exclusivo del Mahāyāna es el de la "naturaleza de Buda" ( buddhadhātu ) o "útero de Tathagata" ( tathāgatagarbha ). La naturaleza de Buda es un concepto que se encuentra en algunos textos budistas del primer milenio de nuestra era, como los sutras Tathāgatagarbha . Según Paul Williams, estos sutras sugieren que "todos los seres sintientes contienen un Tathagata" como su "esencia, naturaleza interior central, Ser". [292] [nota 26] Según Karl Brunnholzl "los primeros sutras mahayana que se basan en y discuten la noción de tathāgatagarbha como el potencial de Buda que es innato en todos los seres sintientes comenzaron a aparecer en forma escrita a fines del siglo II y principios del III". [294] Para algunos, la doctrina parece entrar en conflicto con la doctrina budista anatta (no-Ser), lo que lleva a los eruditos a postular que los Sutras del Tathagatagarbha fueron escritos para promover el budismo entre los no budistas. [295] [296] Esto se puede ver en textos como el Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra , que afirma que la naturaleza de Buda se enseña para ayudar a quienes tienen miedo cuando escuchan la enseñanza de anatta. [297] Textos budistas como el Ratnagotravibhāga aclaran que el "Ser" implícito en la doctrina del Tathagatagarbha es en realidad " no-ser ". [298] [299] Los pensadores budistas han propuesto varias interpretaciones del concepto a lo largo de la historia del pensamiento budista y la mayoría intenta evitar algo parecido a la doctrina hindú del Atman .

Estas ideas budistas indias, de diversas maneras sintéticas, forman la base de la posterior filosofía Mahāyāna en el budismo tibetano y el budismo del este de Asia.

Caminos hacia la liberación

Los Bodhipakkhiyādhammā son siete listas de cualidades o factores que promueven el despertar espiritual ( bodhi ). Cada lista es un breve resumen del camino budista, y las siete listas se superponen sustancialmente. La lista más conocida en Occidente es el Noble Óctuple Sendero , pero se han utilizado y descrito una amplia variedad de caminos y modelos de progreso en las diferentes tradiciones budistas. Sin embargo, generalmente comparten prácticas básicas como sila (ética), samadhi (meditación, dhyana ) y prajña (sabiduría), que se conocen como los tres entrenamientos. Una práctica adicional importante es una actitud amable y compasiva hacia todos los seres vivos y el mundo. La devoción también es importante en algunas tradiciones budistas, y en las tradiciones tibetanas son importantes las visualizaciones de deidades y mandalas. El valor del estudio textual se considera de manera diferente en las diversas tradiciones budistas. Es central para el Theravada y muy importante para el budismo tibetano, mientras que la tradición Zen adopta una postura ambigua.

Un principio rector importante de la práctica budista es el Camino Medio ( madhyamapratipad ). Fue parte del primer sermón de Buda, donde presentó el Noble Camino Óctuple que era un "camino intermedio" entre los extremos del ascetismo y los placeres sensoriales hedonistas. [300] [301] En el budismo, afirma Harvey, la doctrina del "surgimiento dependiente" (surgimiento condicionado, pratītyasamutpāda ) para explicar el renacimiento se considera el "camino intermedio" entre las doctrinas de que un ser tiene un "alma permanente" involucrada en el renacimiento (eternalismo) y "la muerte es definitiva y no hay renacimiento" (aniquilacionismo). [302] [303]

Caminos de liberación en los textos tempranos

Un estilo común de presentación del camino ( mārga ) hacia la liberación en los primeros textos budistas es la "charla graduada", en la que el Buda expone un entrenamiento paso a paso. [304]

En los textos antiguos se pueden encontrar numerosas secuencias diferentes del camino gradual. [305] Una de las presentaciones más importantes y ampliamente utilizadas entre las diversas escuelas budistas es El Noble Óctuple Sendero , o "Óctuple Sendero de los Nobles" (Skt. 'āryāṣṭāṅgamārga' ). Esto se puede encontrar en varios discursos, el más famoso en el Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (El discurso sobre el giro de la rueda del Dharma ).

Otros suttas, como el Tevijja Sutta y el Cula-Hatthipadopama-sutta, ofrecen un esquema diferente del camino, aunque con muchos elementos similares, como la ética y la meditación. [305]

Según Rupert Gethin, el camino hacia el despertar también se resume frecuentemente en otra fórmula corta: "abandono de los obstáculos, práctica de los cuatro principios de la atención plena y desarrollo de los factores del despertar". [306]

Noble Óctuple Sendero

El Óctuple Sendero consiste en un conjunto de ocho factores o condiciones interconectados, que cuando se desarrollan juntos, conducen al cese de dukkha . [307] Estos ocho factores son: Visión Correcta (o Entendimiento Correcto), Intención Correcta (o Pensamiento Correcto), Habla Correcta, Acción Correcta, Modo de Vida Correcto, Esfuerzo Correcto, Atención Correcta y Concentración Correcta.

Este Óctuple Sendero es la cuarta de las Cuatro Nobles Verdades y afirma el camino hacia la cesación de dukkha (sufrimiento, dolor, insatisfacción). [308] [309] El camino enseña que el camino de los iluminados detuvo su ansia, apego y acumulaciones kármicas , y así terminó sus ciclos interminables de renacimiento y sufrimiento. [310] [311] [312]

El Noble Óctuple Sendero se agrupa en tres divisiones básicas , como sigue: [313] [314] [315]

| División | Factor óctuple | Sánscrito, Pali | Descripción |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sabiduría (sánscrito: prajñā , pali: paññā ) | 1. Visión correcta | samyag dṛṣṭi, sammā ditthi | La creencia de que existe una vida después de la muerte y que no todo termina con la muerte, que Buda enseñó y siguió un camino exitoso hacia el nirvana; [313] según Peter Harvey, la visión correcta se sostiene en el budismo como una creencia en los principios budistas del karma y el renacimiento , y la importancia de las Cuatro Nobles Verdades y las Verdaderas Realidades. [316] |

| 2. Intención correcta | samyag saṃkalpa, sammā saṅkappa | Abandonar el hogar y adoptar la vida de un mendicante religioso para seguir el camino; [313] este concepto, afirma Harvey, apunta a la renuncia pacífica, en un ambiente de no sensualidad, no mala voluntad (hacia la bondad amorosa), lejos de la crueldad (hacia la compasión). [316] | |

| Virtudes morales [314] (sánscrito: śīla , pali: sīla ) | 3. Habla correcta | samyag vac, sammā vaca | No mentir, no hablar groseramente, no decirle a una persona lo que otra dice de ella, sino decir lo que conduce a la salvación. [313] |

| 4. Acción correcta | samyag karman, sammā kammanta | No matar ni herir, no tomar lo que no se ha dado; no hay actos sexuales en la vida monástica, [313] para los budistas laicos no hay mala conducta sensual como involucrarse sexualmente con alguien casado o con una mujer soltera protegida por sus padres o parientes. [317] [318] [319] | |

| 5. Medios de vida correctos | samyag ājīvana, sammā ājīva | Para los monjes, mendigar para alimentarse, poseyendo sólo lo que es esencial para sostener la vida. [320] Para los budistas laicos, los textos canónicos establecen que el modo de vida correcto es abstenerse del modo de vida incorrecto, explicado como no convertirse en una fuente o medio de sufrimiento para los seres sensibles engañándolos o dañándolos o matándolos de cualquier manera. [321] [322] | |

| Meditación [314] (sánscrito y pali: samādhi ) | 6. Esfuerzo correcto | samyag vyāyāma, sammā vāyāma | Protegerse de los pensamientos sensuales; este concepto, afirma Harvey, tiene como objetivo prevenir estados malsanos que perturban la meditación. [323] |

| 7. Atención plena correcta | samyag smṛti, sammā sati | Nunca estar distraído, consciente de lo que uno está haciendo; esto, afirma Harvey, fomenta la atención plena sobre la impermanencia del cuerpo, los sentimientos y la mente, así como a experimentar los cinco skandhas , los cinco obstáculos, las cuatro Verdaderas Realidades y los siete factores del despertar. [323] | |

| 8. Concentración correcta | samyag samādhi, samma samādhi | Meditación o concentración correcta ( dhyana ), explicada como los cuatro jhānas. [313] [324] |

Prácticas comunes

Escuchar y aprender el Dharma

En varios suttas que presentan el camino gradual enseñado por el Buda, como el Samaññaphala Sutta y el Cula-Hatthipadopama Sutta, el primer paso en el camino es escuchar al Buda enseñar el Dharma. Esto, a su vez, se dice que conduce a la adquisición de confianza o fe en las enseñanzas del Buda. [305]

Los maestros budistas Mahayana como Yin Shun también afirman que escuchar el Dharma y estudiar los discursos budistas es necesario "si uno quiere aprender y practicar el Dharma del Buda". [325] De la misma manera, en el budismo indo-tibetano, los textos de las "Etapas del Camino" ( Lamrim ) generalmente colocan la actividad de escuchar las enseñanzas budistas como una práctica temprana importante. [326]

Refugio

Tradicionalmente, el primer paso en la mayoría de las escuelas budistas requiere tomar los "Tres Refugios", también llamados las Tres Joyas ( sánscrito : triratna , pali : tiratana ) como base de la práctica religiosa. [327] Esta práctica puede haber sido influenciada por el motivo brahmánico del triple refugio, que se encuentra en el Rigveda 9.97.47, Rigveda 6.46.9 y Chandogya Upanishad 2.22.3–4. [328] El budismo tibetano a veces agrega un cuarto refugio, en el lama . Los budistas creen que los tres refugios son protectores y una forma de reverencia. [327]

La antigua fórmula que se repite para tomar refugio afirma que “voy al Buda como refugio, voy al Dhamma como refugio, voy a la Sangha como refugio”. [329] Recitar los tres refugios, según Harvey, no se considera un lugar para esconderse, sino un pensamiento que “purifica, eleva y fortalece el corazón”. [275]

Sila– Ética budista

Śīla (sánscrito) o sīla (pali) es el concepto de “virtudes morales”, es decir, el segundo grupo y una parte integral del Noble Óctuple Sendero. [316] Generalmente consiste en el habla correcta, la acción correcta y el sustento correcto. [316]

Una de las formas más básicas de ética en el budismo es la adopción de "preceptos". Esto incluye los Cinco Preceptos para los laicos, los Ocho o Diez Preceptos para la vida monástica, así como las reglas del Dhamma ( Vinaya o Patimokkha ) adoptadas por un monasterio. [330] [331]

Otros elementos importantes de la ética budista incluyen la donación o caridad ( dāna ), Mettā (buena voluntad), atención ( Appamada ), respeto por uno mismo ( Hri ) y consideración por las consecuencias ( Apatrapya ).

Preceptos

Las escrituras budistas explican los cinco preceptos ( pali : pañcasīla ; sánscrito : pañcaśīla ) como el estándar mínimo de la moralidad budista. [317] Es el sistema de moralidad más importante en el budismo, junto con las reglas monásticas . [332]

Los cinco preceptos se consideran una formación básica aplicable a todos los budistas. Son: [330] [333] [334]

- “Asumo el precepto de entrenamiento ( sikkha-padam ) de abstenerme de atacar a los seres que respiran”. Esto incluye ordenar o hacer que alguien más mate. Los suttas Pali también dicen que uno no debe “aprobar que otros maten” y que uno debe ser “escrupuloso, compasivo, temeroso por el bienestar de todos los seres vivos”. [335]

- "Asumo el precepto de entrenamiento de abstenerme de tomar lo que no me ha sido dado." Según Harvey, esto también incluye el fraude, el engaño, la falsificación, así como "negar falsamente que uno está en deuda con alguien". [336]

- "Acepto el precepto de entrenamiento de abstenerme de toda mala conducta en lo que respecta a los placeres sensuales". Esto se refiere generalmente al adulterio , así como a la violación y al incesto. También se aplica a las relaciones sexuales con personas que están legalmente bajo la protección de un tutor. También se interpreta de diferentes maneras en las distintas culturas budistas. [337]

- “Asumo el precepto de entrenamiento de abstenerme de hablar falsamente”. Según Harvey, esto incluye “cualquier forma de mentira, engaño o exageración… incluso engaño no verbal mediante gestos u otras indicaciones… o declaraciones engañosas”. [338] A menudo, el precepto también incluye otras formas de habla incorrecta, como “el lenguaje divisivo, las palabras duras, abusivas, airadas e incluso la charla ociosa”. [339]

- "Acepto el precepto de entrenamiento de abstenerme de beber alcohol o de consumir drogas que sean una oportunidad para la negligencia". Según Harvey, la intoxicación es vista como una forma de enmascarar los sufrimientos de la vida en lugar de enfrentarlos. Se considera que es perjudicial para la claridad mental, la atención plena y la capacidad de cumplir con los otros cuatro preceptos. [340]

La adopción y el cumplimiento de los cinco preceptos se basa en el principio de no dañar ( en pali y sánscrito : ahiṃsa ). [341] El Canon Pali recomienda que uno se compare con los demás y, en base a eso, no lastime a los demás. [342] La compasión y la creencia en la retribución kármica forman la base de los preceptos. [343] [344] La adopción de los cinco preceptos es parte de la práctica devocional laica regular, tanto en casa como en el templo local. [345] [346] Sin embargo, el grado en que las personas los mantienen difiere según la región y la época. [347] [346] A veces se los denomina preceptos śrāvakayāna en la tradición Mahāyāna , en contraste con los preceptos del bodhisattva . [348]

Vinaya

El Vinaya es el código de conducta específico para una sangha de monjes o monjas. Incluye el Patimokkha , un conjunto de 227 ofensas que incluyen 75 reglas de decoro para monjes, junto con sanciones por transgresión, en la tradición Theravadin. [349] El contenido preciso del Vinaya Pitaka (escrituras sobre el Vinaya) difiere en diferentes escuelas y tradiciones, y diferentes monasterios establecen sus propios estándares sobre su implementación. La lista de pattimokkha se recita cada quince días en una reunión ritual de todos los monjes. [349] Se han encontrado textos budistas con reglas de vinaya para monasterios en todas las tradiciones budistas, siendo las más antiguas que sobreviven las antiguas traducciones chinas. [350]

Las comunidades monásticas de la tradición budista cortan los lazos sociales normales con la familia y la comunidad y viven como "islas en sí mismas". [351] Dentro de una fraternidad monástica, una sangha tiene sus propias reglas. [351] Un monje se rige por estas reglas institucionalizadas, y vivir la vida como lo prescribe el vinaya no es meramente un medio, sino casi un fin en sí mismo. [351] Las transgresiones por parte de un monje a las reglas del vinaya de la Sangha invitan a la aplicación de las mismas, que pueden incluir la expulsión temporal o permanente. [352]

Restricción y renuncia

Otra práctica importante enseñada por el Buda es la restricción de los sentidos ( indriyasamvara ). En los diversos caminos graduados, esto se presenta generalmente como una práctica que se enseña antes de la meditación sentada formal, y que apoya la meditación al debilitar los deseos sensoriales que son un obstáculo para la meditación. [353] Según Anālayo , la restricción de los sentidos es cuando uno "guarda las puertas de los sentidos para evitar que las impresiones sensoriales conduzcan a los deseos y al descontento". [353] Esto no es una evitación de las impresiones sensoriales, sino una especie de atención consciente hacia las impresiones sensoriales que no se detiene en sus características o signos principales ( nimitta ). Se dice que esto evita que las influencias dañinas entren en la mente. [354] Se dice que esta práctica da lugar a una paz interior y una felicidad que forman una base para la concentración y la introspección. [354]

Una virtud y práctica budista relacionada es la renuncia, o el intento de no tener deseos ( nekkhamma ). [355] Generalmente, la renuncia es el abandono de acciones y deseos que se consideran insalubres en el camino, como la lujuria por la sensualidad y las cosas mundanas. [356] La renuncia se puede cultivar de diferentes maneras. La práctica de dar, por ejemplo, es una forma de cultivar la renuncia. Otra es abandonar la vida laica y convertirse en monástico ( bhiksu o bhiksuni ). [357] Practicar el celibato (ya sea de por vida como monje o temporalmente) también es una forma de renuncia. [358] Muchas historias de Jataka se centran en cómo el Buda practicó la renuncia en vidas pasadas. [359]

Una forma de cultivar la renunciación enseñada por el Buda es la contemplación ( anupassana ) de los «peligros» (o «consecuencias negativas») del placer sensual ( kāmānaṃ ādīnava ). Como parte del discurso gradual, esta contemplación se enseña después de la práctica de la generosidad y la moralidad. [360]

Otra práctica relacionada con la renuncia y la restricción de los sentidos enseñada por el Buda es la "restricción en la comida" o moderación con la comida, que para los monjes generalmente significa no comer después del mediodía. Los laicos devotos también siguen esta regla durante los días especiales de observancia religiosa ( uposatha ). [361] La observancia del Uposatha también incluye otras prácticas que tratan sobre la renuncia, principalmente los ocho preceptos .

Para los monjes budistas, la renuncia también se puede entrenar a través de varias prácticas ascéticas opcionales llamadas dhutaṅga .

En diferentes tradiciones budistas se siguen otras prácticas relacionadas que se centran en el ayuno .

Atención plena y comprensión clara

El entrenamiento de la facultad llamada “atención plena” (Pali: sati , sánscrito: smṛti, que literalmente significa “recuerdo, recordar”) es central en el budismo. Según Analayo, la atención plena es una conciencia plena del momento presente que mejora y fortalece la memoria. [362] El filósofo budista indio Asanga definió la atención plena de esta manera: “Es el no olvido por parte de la mente con respecto al objeto experimentado. Su función es la no distracción”. [363] Según Rupert Gethin, sati es también “una conciencia de las cosas en relación con las cosas, y por lo tanto una conciencia de su valor relativo”. [364]

There are different practices and exercises for training mindfulness in the early discourses, such as the four Satipaṭṭhānas (Sanskrit: smṛtyupasthāna, "establishments of mindfulness") and Ānāpānasati (Sanskrit: ānāpānasmṛti, "mindfulness of breathing").

A closely related mental faculty, which is often mentioned side by side with mindfulness, is sampajañña ("clear comprehension"). This faculty is the ability to comprehend what one is doing and is happening in the mind, and whether it is being influenced by unwholesome states or wholesome ones.[365]

Meditation – Sama-amādhi and dhyāna

A wide range of meditation practices has developed in the Buddhist traditions, but "meditation" primarily refers to the attainment of samādhi and the practice of dhyāna (Pali: jhāna). Samādhi is a calm, undistracted, unified and concentrated state of awareness. It is defined by Asanga as "one-pointedness of mind on the object to be investigated. Its function consists of giving a basis to knowledge (jñāna)."[363]Dhyāna is "state of perfect equanimity and awareness (upekkhā-sati-parisuddhi)," reached through focused mental training.[366]

The practice of dhyāna aids in maintaining a calm mind and avoiding disturbance of this calm mind by mindfulness of disturbing thoughts and feelings.[367][note 27]

Origins

The earliest evidence of yogis and their meditative tradition, states Karel Werner, is found in the Keśin hymn 10.136 of the Rigveda.[368] While evidence suggests meditation was practised in the centuries preceding the Buddha,[369] the meditative methodologies described in the Buddhist texts are some of the earliest among texts that have survived into the modern era.[370][371] These methodologies likely incorporate what existed before the Buddha as well as those first developed within Buddhism.[372][note 28]

There is no scholarly agreement on the origin and source of the practice of dhyāna. Some scholars, like Bronkhorst, see the four dhyānas as a Buddhist invention.[376] Alexander Wynne argues that the Buddha learned dhyāna from Brahmanical teachers.[377]

Whatever the case, the Buddha taught meditation with a new focus and interpretation, particularly through the four dhyānas methodology,[378] in which mindfulness is maintained.[379][380] Further, the focus of meditation and the underlying theory of liberation guiding the meditation has been different in Buddhism.[369][381][382] For example, states Bronkhorst, the verse 4.4.23 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad with its "become calm, subdued, quiet, patiently enduring, concentrated, one sees soul in oneself" is most probably a meditative state.[383] The Buddhist discussion of meditation is without the concept of soul and the discussion criticises both the ascetic meditation of Jainism and the "real self, soul" meditation of Hinduism.[384]

The formless attainments

Often grouped into the jhāna-scheme are four other meditative states, referred to in the early texts as arupa samāpattis (formless attainments). These are also referred to in commentarial literature as immaterial/formless jhānas (arūpajhānas). The first formless attainment is a place or realm of infinite space (ākāsānañcāyatana) without form or colour or shape. The second is termed the realm of infinite consciousness (viññāṇañcāyatana); the third is the realm of nothingness (ākiñcaññāyatana), while the fourth is the realm of "neither perception nor non-perception".[385] The four rupa-jhānas in Buddhist practice leads to rebirth in successfully better rupa Brahma heavenly realms, while arupa-jhānas leads into arupa heavens.[386][387]

Meditation and insight

In the Pali canon, the Buddha outlines two meditative qualities which are mutually supportive: samatha (Pāli; Sanskrit: śamatha; "calm") and vipassanā (Sanskrit: vipaśyanā, insight).[388] The Buddha compares these mental qualities to a "swift pair of messengers" who together help deliver the message of nibbana (SN 35.245).[389]

The various Buddhist traditions generally see Buddhist meditation as being divided into those two main types.[390][391] Samatha is also called "calming meditation", and focuses on stilling and concentrating the mind i.e. developing samadhi and the four dhyānas. According to Damien Keown, vipassanā meanwhile, focuses on "the generation of penetrating and critical insight (paññā)".[392]

There are numerous doctrinal positions and disagreements within the different Buddhist traditions regarding these qualities or forms of meditation. For example, in the Pali Four Ways to Arahantship Sutta (AN 4.170), it is said that one can develop calm and then insight, or insight and then calm, or both at the same time.[393] Meanwhile, in Vasubandhu's Abhidharmakośakārikā, vipaśyanā is said to be practiced once one has reached samadhi by cultivating the four foundations of mindfulness (smṛtyupasthānas).[394]

Beginning with comments by La Vallee Poussin, a series of scholars have argued that these two meditation types reflect a tension between two different ancient Buddhist traditions regarding the use of dhyāna, one which focused on insight based practice and the other which focused purely on dhyāna.[102][395] However, other scholars such as Analayo and Rupert Gethin have disagreed with this "two paths" thesis, instead seeing both of these practices as complementary.[395][396]

The Brahma-vihara

The four immeasurables or four abodes, also called Brahma-viharas, are virtues or directions for meditation in Buddhist traditions, which helps a person be reborn in the heavenly (Brahma) realm.[397][398][399] These are traditionally believed to be a characteristic of the deity Brahma and the heavenly abode he resides in.[400]

The four Brahma-vihara are:

- Loving-kindness (Pāli: mettā, Sanskrit: maitrī) is active good will towards all;[398][401]

- Compassion (Pāli and Sanskrit: karuṇā) results from metta; it is identifying the suffering of others as one's own;[398][401]

- Empathetic joy (Pāli and Sanskrit: muditā): is the feeling of joy because others are happy, even if one did not contribute to it; it is a form of sympathetic joy;[401]

- Equanimity (Pāli: upekkhā, Sanskrit: upekṣā): is even-mindedness and serenity, treating everyone impartially.[398][401]

Tantra, visualization and the subtle body

Some Buddhist traditions, especially those associated with Tantric Buddhism (also known as Vajrayana and Secret Mantra) use images and symbols of deities and Buddhas in meditation. This is generally done by mentally visualizing a Buddha image (or some other mental image, like a symbol, a mandala, a syllable, etc.), and using that image to cultivate calm and insight. One may also visualize and identify oneself with the imagined deity.[402][403] While visualization practices have been particularly popular in Vajrayana, they may also found in Mahayana and Theravada traditions.[404]

In Tibetan Buddhism, unique tantric techniques which include visualization (but also mantra recitation, mandalas, and other elements) are considered to be much more effective than non-tantric meditations and they are one of the most popular meditation methods.[405] The methods of Unsurpassable Yoga Tantra, (anuttarayogatantra) are in turn seen as the highest and most advanced. Anuttarayoga practice is divided into two stages, the Generation Stage and the Completion Stage. In the Generation Stage, one meditates on emptiness and visualizes oneself as a deity as well as visualizing its mandala. The focus is on developing clear appearance and divine pride (the understanding that oneself and the deity are one).[406] This method is also known as deity yoga (devata yoga). There are numerous meditation deities (yidam) used, each with a mandala, a circular symbolic map used in meditation.[407]

Insight and knowledge

Prajñā (Sanskrit) or paññā (Pāli) is wisdom, or knowledge of the true nature of existence. Another term which is associated with prajñā and sometimes is equivalent to it is vipassanā (Pāli) or vipaśyanā (Sanskrit), which is often translated as "insight". In Buddhist texts, the faculty of insight is often said to be cultivated through the four establishments of mindfulness.[408] In the early texts, Paññā is included as one of the "five faculties" (indriya) which are commonly listed as important spiritual elements to be cultivated (see for example: AN I 16). Paññā along with samadhi, is also listed as one of the "trainings in the higher states of mind" (adhicittasikkha).[408]

The Buddhist tradition regards ignorance (avidyā), a fundamental ignorance, misunderstanding or mis-perception of the nature of reality, as one of the basic causes of dukkha and samsara. Overcoming this ignorance is part of the path to awakening. This overcoming includes the contemplation of impermanence and the non-self nature of reality,[409][410] and this develops dispassion for the objects of clinging, and liberates a being from dukkha and saṃsāra.[411][412][413]

Prajñā is important in all Buddhist traditions. It is variously described as wisdom regarding the impermanent and not-self nature of dharmas (phenomena), the functioning of karma and rebirth, and knowledge of dependent origination.[414] Likewise, vipaśyanā is described in a similar way, such as in the Paṭisambhidāmagga, where it is said to be the contemplation of things as impermanent, unsatisfactory and not-self.[415]

Devotion

Most forms of Buddhism "consider saddhā (Sanskrit: śraddhā), 'trustful confidence' or 'faith', as a quality which must be balanced by wisdom, and as a preparation for, or accompaniment of, meditation."[416] Because of this devotion (Sanskrit: bhakti; Pali: bhatti) is an important part of the practice of most Buddhists.[417] Devotional practices include ritual prayer, prostration, offerings, pilgrimage, and chanting.[418] Buddhist devotion is usually focused on some object, image or location that is seen as holy or spiritually influential. Examples of objects of devotion include paintings or statues of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, stupas, and bodhi trees.[419] Public group chanting for devotional and ceremonial is common to all Buddhist traditions and goes back to ancient India where chanting aided in the memorization of the orally transmitted teachings.[420] Rosaries called malas are used in all Buddhist traditions to count repeated chanting of common formulas or mantras. Chanting is thus a type of devotional group meditation which leads to tranquility and communicates the Buddhist teachings.[421]

Vegetarianism and animal ethics

Based on the Indian principle of ahimsa (non-harming), the Buddha's ethics strongly condemn the harming of all sentient beings, including all animals. He thus condemned the animal sacrifice of the Brahmins as well hunting, and killing animals for food.[422] However, early Buddhist texts depict the Buddha as allowing monastics to eat meat. This seems to be because monastics begged for their food and thus were supposed to accept whatever food was offered to them.[423] This was tempered by the rule that meat had to be "three times clean": "they had not seen, had not heard, and had no reason to suspect that the animal had been killed so that the meat could be given to them".[424] Also, while the Buddha did not explicitly promote vegetarianism in his discourses, he did state that gaining one's livelihood from the meat trade was unethical.[425] In contrast to this, various Mahayana sutras and texts like the Mahaparinirvana sutra, Surangama sutra and the Lankavatara sutra state that the Buddha promoted vegetarianism out of compassion.[426] Indian Mahayana thinkers like Shantideva promoted the avoidance of meat.[427] Throughout history, the issue of whether Buddhists should be vegetarian has remained a much debated topic and there is a variety of opinions on this issue among modern Buddhists.

Texts

.jpg/440px-Nava_Jetavana_Temple_-_Shravasti_-_013_First_Council_at_Rajagaha_(9241729223).jpg)