Wurundjeri

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Woiwurrung, English | |

| Religion | |

| Aboriginal mythology, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Boonwurrung, Dja Dja Wurrung, Taungurung, Wathaurong see List of Indigenous group names |

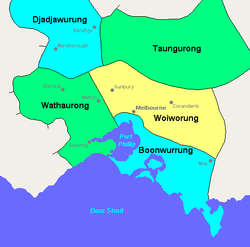

The Wurundjeri people are an Aboriginal people of the Woiwurrung language group, in the Kulin nation. They are the traditional owners of the Yarra River Valley, covering much of the present location of Melbourne. They continue to live in this area and throughout Australia. They were called the Yarra tribe by early European colonists.

The Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council was established in 1985 by Wurundjeri people.

Ethnonym

According to the early Australian ethnographer Alfred William Howitt, the name Wurundjeri, in his transcription Urunjeri, refers to a species of eucalypt, Eucalyptus viminalis, otherwise known as the manna or white gum, which is common along the Yarra River.[1] Some modern reports of Wurundjeri traditional lore state that their ethnonym combines a word, wurun, meaning Manna gum/"white gum tree"[2] and djeri, a species of grub found in the tree, and take the word therefore to mean "Witchetty Grub People".[3]

Language

Wurundjeri people speak Woiwurrung, a dialect of Kulin. Kulin is spoken by the five groups in the Kulin nation.

Country

In Norman Tindale's estimation – and his data, drawing on R. H. Mathews's data which has been challenged[4] – Wurundjeri lands as extending over approximately 12,500 km2 (4,800 sq mi). These took in the areas of the Yarra and Saltwater rivers around Melbourne, and ran north as far as Mount Disappointment, northwest to Macedon, Woodend, and Lancefield. Their eastern borders went as far as Mount Baw Baw and Healesville. Their southern confines approached Mordialloc, Warragul, and Moe.[5]

In June 2021, the boundaries between the land of two of the traditional owner groups in greater Melbourne, the Wurundjeri and Boonwurrung, were agreed between the two groups, after being drawn up by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council. The new borderline runs across the city from west to east, with the CBD, Richmond and Hawthorn included in Wurundjeri land, and Albert Park, St Kilda and Caulfield on Bunurong land. It was agreed that Mount Cottrell, the site of a massacre in 1836 with at least 10 Wathaurong victims, would be jointly managed above the 160 m (520 ft) line. The two Registered Aboriginal Parties representing the two groups were the Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation and the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation. However, these borders are still in dispute among several prominent figures and Wurundjeri territory has been claimed to spread much further west and south.[6]

Clans

The Wurundjeri balluk[a] was composed of two patrilines who resided in two distinct localities. These were respectively the Wurundjeri-willam and the Baluk-willam,[7] where willam means "camping ground"/dwelling.[8][9]

The Wurundjeri Willum resided throughout the territory on the Yarra running along its sources as far as Mount Baw Baw and to the area where it forms a junction with the Maribyrnong River.[2]

The Balluk-willam's territory cover an area from Mt. Baw Baw: Their territory covers the area south from Mount Baw Baw to Dandenong, Cranbourne and the swampland at the head of Western Port bay.[2]

History

As colonization began, it was estimated that something of the order of 11,500-15,000 Aborigines, composed of some 38 tribal groups, were living in the area of Victoria.[10][11] The earliest European settlers came across a park-like landscape extending inland from Melbourne, consisting of large areas of grassy plains to the north and southwest, with little forest cover, something thought to be testimony of indigenous sheet burning practices to expose the massive number of yam daisies which proliferated in the area.[12] These roots and various tuber lilies formed a major source of starch and carbohydrates.[13] Seasonal changes in the weather, availability of foods and other factors would determine where campsites were located, many near the Birrarung and its tributaries.

The Wurundjeri and Gunung Willam Balug clans mined diorite at Mount William stone axe quarry which was a source of the highly valued greenstone hatchet heads, which were traded across a wide area as far as New South Wales and Adelaide. The mine provided a complex network of trading for economic and social exchange among the different Aboriginal nations in Victoria.[14][15] The quarry had been in use for more than 1,500 years and covered 18 hectares including underground pits of several metres. In February 2008 the site was placed on the Australian National Heritage List for its cultural importance and archeological value.[16]

Settlement and dispossession of the Wurundjeri lands began soon after a ceremony in which Wurundjeri leaders conducted a tanderrum ceremony, whose function was to allow outsiders temporary access to the resources of clan lands. John Batman and other whites interpreted this symbolic act, recorded in treaty form, as equivalent to medieval enfeoffment of all Woiwurrong territory.[2] Within a few years settlement began around Pound Bend with Major Charles Newman at Mullum Mullum Creek in 1838, and James Anderson on Beal Yallock, now known as Anderson's Creek a year later. Their measures to clear the area of Aboriginals was met with guerrilla skirmishing, led by Jaga Jaga, with the appropriation of cattle and the burning of fields. They were armed with rifles, and esteemed to be excellent marksmen, firing close to Anderson to drive him off as they helped themselves to his potato crop while en route to Yering in 1840. A trap set there by Captain Henry Gibson led to Jaga Jaga's capture and a battle as the Wurundjeri fought unsuccessfully to secure his release. Resistance was broken, and settlements throve. One elder, Derrimut, later stated:

You see…all this mine. All along here Derrimut's once. No matter now, me soon tumble down…Why me have no lubra? Why me have no piccaninny? You have all this place. No good have children, no good have lubra. Me tumble down and die very soon now.[17][18]

Coranderrk

In 1863 the surviving members of the Wurundjeri tribe were given "permissive occupancy" of Coranderrk Station, near Healesville and forcibly resettled. Despite numerous petitions, letters, and delegations to the Colonial and Federal Government, the grant of this land in compensation for the country lost was refused. Coranderrk was closed in 1924 and its occupants bar five refusing to leave Country were again moved to Lake Tyers in Gippsland.

Wurundjeri today

All remaining Wurundjeri people are descendants of Bebejan, through his daughter Annie Borate (Boorat), and in turn, her son Robert Wandin (Wandoon). Bebejan was a Ngurungaeta of the Wurundjeri people and was present at John Batman's "treaty" signing in 1835.[19] Joy Murphy Wandin, a Wurundjeri elder, explains the importance of preserving Wurundjeri culture:

In the recent past, Wurundjeri culture was undermined by people being forbidden to "talk culture" and language. Another loss was the loss of children taken from families. Now, some knowledge of the past must be found and collected from documents. By finding and doing this, Wurundjeri will bring their past to the present and recreate a place of belonging. A "keeping place" should be to keep things for future generations of our people, not a showcase for all, not a resource to earn dollars. I work towards maintaining the Wurundjeri culture for Wurundjeri people into the future.[b]

In 1985, the Wurundjeri Tribe Land Compensation and Cultural Heritage Council was established to fulfil statutory roles under Commonwealth and Victorian legislation and to assist in raising awareness of Wurundjeri culture and history within the wider community.[20][21]

Wurundjeri elders often attend events with visitors present where they give the traditional welcome to country greeting in the Woiwurrung language:

Wominjeka yearmenn koondee-bik Wurundjeri-Ballak

which means, "Welcome to the land of the Wurundjeri people".[22][23]

Notable people

- Bebejan (?-1836): ngurungaeta, and William Barak's father and Billibellary's brother

- Billibellary (1799–1846): ngurungaeta of the Wurundjeri-willam clan.

- Simon Wonga (1824–1874): ngurungaeta by 1851 until his death. Billibellary's son.[24]

- William Barak (1824–1903): ngurungaeta of the Wurundjeri-willam clan from 1874 until his death.

- James Wandin (1933–2006): ngurungaeta until his death, and an Australian rules footballer

- Murrundindi: ngurungaeta from 2006 until present

Other notable Wurundjeri people include:

- Tullamareena: present during the founding of Melbourne

- Derrimut (1810–1864): a Bunurong elder associated with the Woiwurrung, present during British invasion

- Diane Kerr: elder

- Winnie Quagliotti (1931–1988): elder

- Joy Murphy Wandin: senior elder

Alternative names/spellings

- Coraloon (?)

- Gungung-willam

- Kukuruk (northern clan name)

- Mort Noular (language name)

- Ngarukwillam

- N'uther Galla

- Nuthergalla (ngatha = juða "no" in the Melbourne dialect).[25]

- Oorongie

- Urunjeri[26]

- Waarengbadawa

- Wainworra

- Wairwaioo

- Warerong

- Warorong

- Warwaroo

- Wavoorong

- Wawoorong, Wawoorong

- Wawurong

- Wawurrong

- Woeworung

- Woiworung (name for the language they spoke, from woi + worung = speech)

- Woiwurru (woi = no + wur:u = lip)

- Woiwurung, Woiwurong, Woiwurrong

- Wooeewoorong

- Wowerong

- Wurrundyirra-baluk

- Wurunjeri

- Wurunjerri

- Wurunjerri-baluk

- Yarra Yarra

- Yarra Yarra Coolies (kulin = man)

See also

- Wurundjeri Tribe Land Compensation and Cultural Heritage Council

- Batman's Treaty

- Indigenous Australians

- Australian Aboriginal enumeration

- Battle of Yering

- Possum-skin cloak

- Bunurong

- Gunai people

Notes

- ^ Balluk was a suffix referring to a number of people in the noun it is attached to (Barwick 1984, p. 122).

- ^ Joy Murphy Wandin quoted in Ellender & Christiansen 2001, p. 121

Citations

- ^ Howitt 1889, p. 109, note 2.

- ^ a b c d Barwick 1984, p. 122.

- ^ Ellender & Christiansen 2001, p. 35.

- ^ Barwick 1984, pp. 100–103.

- ^ Tindale 1974, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Dunstan 2021.

- ^ Barwick 1984, pp. 120, 122.

- ^ Fels 2011, p. xxi.

- ^ Nicholson 2016.

- ^ Barwick 1984, p. 109,n.13.

- ^ Warren 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Gammage 2012, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Pascoe 1947.

- ^ McBryde 1984, p. 44.

- ^ Presland 1994.

- ^ National Heritage List.

- ^ Jaga Jaga's Resistance War.

- ^ Clark 2005, p. ?.

- ^ VAHC 2008.

- ^ Abbotsford Convent Muse 2007.

- ^ Gardiner & McGaw 2018, p. 22.

- ^ Wandin 2000.

- ^ Flanagan 2003.

- ^ SLV: Simon Wonga.

- ^ Tindale 1974, p. 209.

- ^ Howitt 1889, p. 109.

Sources

- "The Abbotsford Convent Muse, Issue 18" (PDF). September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- "AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia". AIATSIS. 18 June 2021.

- "Ancestors & Past". Wurundjeri Tribe Council. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- Barwick, Diane E. (1984). McBryde, Isabel (ed.). "Mapping the past: an atlas of Victorian clans 1835–1904". Aboriginal History. 8 (2): 100–131. JSTOR 24045800.

- "Batmania: The Deed, National Museum of Australia". Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Broome, Richard (2005). Aboriginal Victorians: A History Since 1800. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-741-14569-4.

- Brown, Peter. "The Keilor Cranium". Peter Brown's Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Clark, Ian D. (1 December 2005). ""You have all this place, no good have children ..." Derrimut: traitor, saviour, or a man of his people?". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 91 (2): 107–132.

- Decision in relation to an Application by Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc to be a Registered Aboriginal Party. Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council. 22 August 2008.

- Dunstan, Joseph (26 June 2021). "Melbourne's birth destroyed Bunurong and Wurundjeri boundaries. 185 years on, they've been redrawn". ABC News. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Eidelson, Meyer (2000) [First published 1997]. The Melbourne Dreaming: A Guide to the Aboriginal Places of Melbourne. Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Ellender, Isabel; Christiansen, Peter (2001). People of the Merri Merri. The Wurundjeri in Colonial Days. Merri Creek Management Committee. ISBN 978-0-9577728-0-9.

- Fels, Marie (2011). 'I Succeeded Once': The Aboriginal Protectorate on the Mornington Peninsula, 1839–1840 (PDF). ANU Press. ISBN 978-1-921-86212-0.

- Flanagan, Martin (25 January 2003). "Tireless ambassador bids you welcome". The Age. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- Flannery, Tim (2002) [First published 1852]. "Introduction". In Morgan, John (ed.). The Life and Adventures of William Buckley. ISBN 978-1-877-00820-7.

- Fleming, James (2002). Currey, John (ed.). A journal of Grimes' survey: the Cumberland in Port Phillip January–February 1803. Banks Society Publications. ISBN 978-0-949586-10-0. cited in Rhodes 2003, p. 24

- Gammage, Bill (2012) [First published 2011]. The biggest estate on earth: how Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-743-31132-5.

- Gannaway, Kath (24 January 2007). "Important step for reconciliation". Star News Group. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- Gardiner, Aunty Margaret; McGaw, Janet (2018). "'Indigenous Placemaking in Urban Melbourne: A Dialogue Between a Wurundjeri Elder and a Non-Indigenous Architect and Academic". In Grant, Elizabeth; Greenop, Kelly; Refiti, Albert L.; Glenn, Daniel J. (eds.). The Handbook of Contemporary Indigenous Architecture. Springer. pp. 581–605. ISBN 978-9-811-06904-8.

- "Governor Bourke's Proclamation 1835 (UK)". National Archives of Australia: I. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Hinds, Richard (24 May 2002). "Marn Grook, a native game on Sydney's biggest stage". The Age. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Howitt, A. W. (1889). "On the organisation of Australian tribes". Transactions of the Royal Society of Victoria. 1 (2): 96–137 – via BHL.

- Hunter, Ian (2004–2005). "Yarra Creation Story". Wurundjeri Dreaming. Archived from the original on 4 November 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "Indigenous Sporting Heroes: History of the Wurundjeri People". n.d. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- "Interview with Megan Goulding, CEO Wurundjeri Inc" (PDF). Abbotsford Convent Muse. No. 18. September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- "Jaga Jaga's Resistance War" (PDF). Nillumbik Reconciliation Group.

- "Management of Wurundjeri Properties & Significant Places". Wurundjeri Tribe Council. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- McBryde, Isabel (October 1984). "Kulin Greenstone Quarries: The Social Contexts of Production and Distribution for the Mt William Site". World Archaeology. 16 (2): 267–285. doi:10.1080/00438243.1984.9979932. JSTOR 124577.

- "National Heritage List: Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry". Department of the Environment and Energy. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Nicholson, Bill and Mandy (2016). Wurundjeri's Cultural Heritage of the Melton Area (PDF). Melbourne: Melton City Council.

- Pascoe, Bruce (1947). Dark emu black seeds: agriculture or accident?. ISBN 978-1-922142-44-3. OCLC 930855686.

- Presland, Gary. "Keilor Archaeological Site". Online Encyclopedia of Melbourne (eMelbourne). Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Presland, Gary (1994). Aboriginal Melbourne. The lost land of the Kulin people. McPhee Gribble. ISBN 978-0-86914-346-9.

- Presland, Gary (1997). The First Residents of Melbourne's Western Region. Harriland Press. ISBN 978-0-646-33150-8.

- Rhodes, David (August 2003). "Channel Deepening Existing Conditions Final Report – Aboriginal Heritage" (PDF). Parsons Brinckerhoff & Port of Melbourne Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Rowley, C.D. (1970). The Destruction of Aboriginal Society. Penguin Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-14-021452-9.

- "Simon Wonga". State Library of Victoria. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009.

- Steyne, Hanna (2001). "Investigating the Submerged Landscapes of Port Phillip Bay, Victoria" (PDF). Heritage Victoria. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Thomas, William (1898). Bride, Thomas Francis (ed.). Letters from Victorian Pioneers. Public Library of Victoria – via Internet Archive.

- Thompson, David (27 September 2007). "Aborigines were playing possum". Herald Sun. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- Toscano, Joseph (2008). Lest We Forget. The Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner Saga. Anarchist Media Institute. ISBN 978-0-9758219-4-7.

- Wandin, James (26 May 2000). "An address to the Parliament of Victoria". Parliament of Victorian. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- Warren, Marilyn (21 April 2011). "Early History of the Victorian Legal System". Monash University. JSTOR community.34616455.

- Web, Carolyn (3 June 2005). "History should have no divide". The Age. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Wiencke, Shirley W. (1984). When the Wattles Bloom Again: The Life and Times of William Barak, Last Chief of the Yarra Yarra Tribe. S.W. Wiencke. ISBN 978-0-9590549-0-3.