Fur seal

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

| Fur seal | |

|---|---|

| |

| A group of brown fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Clade: | Pinnipedia |

| Family: | Otariidae |

| Subfamily: | Arctocephalinae Scheffer & Rice 1963 |

| Genera | |

Fur seals are any of nine species of pinnipeds belonging to the subfamily Arctocephalinae in the family Otariidae. They are much more closely related to sea lions than true seals, and share with them external ears (pinnae), relatively long and muscular foreflippers, and the ability to walk on all fours. They are marked by their dense underfur, which made them a long-time object of commercial hunting. Eight species belong to the genus Arctocephalus and are found primarily in the Southern Hemisphere, while a ninth species also sometimes called fur seal, the Northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus), belongs to a different genus and inhabits the North Pacific. The fur seals in Arctocephalus are more closely related to sea lions than they are to the Northern fur seal, but all three groups are more closely related to one another than they are to true seals.

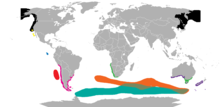

Taxonomy

Fur seals and sea lions make up the family Otariidae. Along with the Phocidae and Odobenidae, ottariids are pinnipeds descending from a common ancestor most closely related to modern bears (as hinted by the subfamily Arctocephalinae, meaning "bear-headed"). The name pinniped refers to mammals with front and rear flippers. Otariids arose about 15-17 million years ago in the Miocene, and were originally land mammals that rapidly diversified and adapted to a marine environment, giving rise to the semiaquatic marine mammals that thrive today. Fur seals and sea lions are closely related and commonly known together as the "eared seals". Until recently, fur seals were all grouped under a single subfamily of Pinnipedia, called the Arctocephalinae, to contrast them with Otariinae – the sea lions – based on the most prominent common feature, namely the coat of dense underfur intermixed with guard hairs. Recent genetic evidence, however, suggests Callorhinus is more closely related to some sea lion species, and the fur seal/sea lion subfamily distinction has been eliminated from many taxonomies. Nonetheless, all fur seals have certain features in common: the fur, generally smaller sizes, farther and longer foraging trips, smaller and more abundant prey items, and greater sexual dimorphism. For these reasons, the distinction remains useful. Fur seals comprise two genera: Callorhinus, and Arctocephalus. Callorhinus is represented by just one species in the Northern Hemisphere, the northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus), and Arctocephalus is represented by eight species in the Southern Hemisphere. The southern fur seals comprising the genus Arctocephalus include Antarctic fur seals, Galapagos fur seals, Juan Fernandez fur seals, New Zealand fur seals, brown fur seals, South American fur seals, and subantarctic fur seals.

| Image | Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

.jpg/440px-091130_rosita_bay_south_georgia_2563_(4172615911).jpg) | Arctocephalus É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire & F. Cuvier in F. Cuvier, 1826 |

|

| Callorhinus Gray, 1859 |

|

Physical appearance

Along with the previously mentioned thick underfur, fur seals are distinguished from sea lions by their smaller body structure, greater sexual dimorphism, smaller prey, and longer foraging trips during the feeding cycle. The physical appearance of fur seals varies with individual species, but the main characteristics remain constant.

Fur seals are characterized by their external pinnae, dense underfur, vibrissae, and long, muscular limbs. They share with other otariids the ability to rotate their rear limbs forward, supporting their bodies and allowing them to ambulate on land. In water, their front limbs, typically measuring about a fourth of their body length, act as oars and can propel them forward for optimal mobility. The surfaces of these long, paddle-like fore limbs are leathery with small claws. Otariids have a dog-like head, sharp, well-developed canines, sharp eyesight, and keen hearing.

They are extremely sexually dimorphic mammals, with the males often two to five times the size of the females, with proportionally larger heads, necks, and chests. Size ranges from about 1.5 m, 64 kg in the male Galapagos fur seal (also the smallest pinniped) to 2.5 m, 180 kg in the adult male New Zealand fur seal. Most fur seal pups are born with a black-brown coat that molts at 2–3 months, revealing a brown coat that typically gets darker with age. Some males and females within the same species have significant differences in appearance, further contributing to the sexual dimorphism. Females and juveniles often have a lighter colored coat overall or only on the chest, as seen in South American fur seals. In a northern fur seal population, the females are typically silvery-gray on the dorsal side and reddish-brown on their ventral side with a light gray patch on their chest. This makes them easily distinguished from the males with their brownish-gray to reddish-brown or black coats.

Habitat

Of the fur seal family, eight species are considered southern fur seals, and only one is found in the Northern Hemisphere. The southern group includes Antarctic, Galapagos, Guadalupe, Juan Fernandez, New Zealand, brown, South American, and subantarctic fur seals. They typically spend about 70% of their lives in subpolar, temperate, and equatorial waters. Colonies of fur seals can be seen throughout the Pacific and Southern Oceans from south Australia, Africa, and New Zealand, to the coast of Peru and north to California. They are typically nonmigrating mammals, with the exception of the northern fur seal, which has been known to travel distances up to 10,000 km. Fur seals are often found near isolated islands or peninsulas, and can be seen hauling out onto the mainland during winter. Although they are not migratory, they have been observed wandering hundreds of miles from their breeding grounds in times of scarce resources. For example, the subantarctic fur seal typically resides near temperate islands in the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans north of the Antarctic Polar Front, but juvenile males have been seen wandering as far north as Brazil and South Africa.

Behavior and ecology

Typically, fur seals gather during the summer in large rookeries at specific beaches or rocky outcrops to give birth and breed. All species are polygynous, meaning dominant males reproduce with more than one female. For most species, total gestation lasts about 11.5 months, including a several-month period of delayed implantation of the embryo. Northern fur seal males aggressively select and defend the specific females in their harems.[1] Females typically reach sexual maturity around 3–4 years. The males reach sexual maturity around the same time, but do not become territorial or mate until 6–10 years.

The breeding season typically begins in November and lasts 2–3 months. The northern fur seals begin their breeding season as early as June due to their region, climate, and resources. In all cases, the males arrive a few weeks early to fight for their territory and groups of females with which to mate. They congregate at rocky, isolated breeding grounds and defend their territory through fighting and vocalization. Males typically do not leave their territory for the entirety of the breeding season, fasting and competing until all energy sources are depleted.

The Juan Fernandez fur seals deviate from this typical behavior, using aquatic breeding territories not seen in other fur seals. They use rocky sites for breeding, but males fight for territory on land and on the shoreline and in the water. Upon arriving to the breeding grounds, females give birth to their pups from the previous season. About a week later, the females mate again and shortly after begin their feeding cycle, which typically consists of foraging and feeding at sea for about 5 days, then returning to the breeding grounds to nurse the pups for about 2 days. Mothers and pups locate each other using call recognition during nursing period. The Juan Fernandez fur seal has a particularly long feeding cycle, with about 12 days of foraging and feeding and 5 days of nursing. Most fur seals continue this cycle for about 9 months until they wean their pup. The exception to this is the Antarctic fur seal, which has a feeding cycle that lasts only 4 months. During foraging trips, most female fur seals travel around 200 km from the breeding site, and can dive around 200 m depending on food availability.

The remainder of the year, fur seals lead a largely pelagic existence in the open sea, pursuing their prey wherever it is abundant. They feed on moderately sized fish, squid, and krill. Several species of the southern fur seal also have sea birds, especially penguins, as part of their diets.[2][3] Fur seals, in turn, are preyed upon by sharks, orcas, and occasionally by larger sea lions. These opportunistic mammals tend to feed and dive in shallow waters at night, when their prey are swimming near the surface. Fur seals occasionally gang up and evict sharks.[4] South American fur seals exhibit a different diet; adults feed almost exclusively on anchovies, while juveniles feed on demersal fish, most likely due to availability.

When fur seals were hunted in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, they hauled out on remote islands where no predators were present. The hunters reported being able to club the unwary animals to death one after another, making the hunt profitable, though the price per seal skin was low.[5]

Population and survival

The average lifespan of fur seals varies with different species from 13 to 25 years, with females typically living longer. Most populations continue to expand as they recover from previous commercial hunting and environmental threats. Many species were heavily exploited by commercial sealers, especially during the 19th century, when their fur was highly valued. Beginning in the 1790s, the ports of Stonington and New Haven, Connecticut, were leaders of the American fur seal trade, which primarily entailed clubbing fur seals to death on uninhabited South Pacific islands, skinning them, and selling the hides in China.[5] Many populations, notably the Guadalupe fur seal, northern fur seal, and Cape fur seal, suffered dramatic declines and are still recovering. Currently, most species are protected, and hunting is mostly limited to subsistence harvest. Globally, most populations can be considered healthy, mostly because they often prefer remote habitats that are relatively inaccessible to humans. Nonetheless, environmental degradation, competition with fisheries, and climate change potentially pose threats to some populations.

See also

References

- ^ Fur Seals (Arctocephalinae). afsc.noaa.gov

- ^ Daneri, G. A.; Carlini, A. R.; Harrington, A.; Balboni, L.; Hernandez, C. M. (2008). "Interannual variation in the diet of non-breeding male Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, at Isla 25 de Mayo/King George Island". Polar Biology. 31 (11): 1365. Bibcode:2008PoBio..31.1365D. doi:10.1007/s00300-008-0475-3. hdl:11336/135116. S2CID 13332236.

- ^ Nigel W Bonner, S Hunter (1982). "Predatory interactions between Antarctic fur seals, macaroni penguins and giant petrels" (PDF). British Antarctic Survey Bulletin. 56: 75–79. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-31.

- ^ Pare, Sascha (4 November 2023). "Watch great white shark get mobbed by gang of seals in 'incredible and surprising' footage". livescience.com.

- ^ a b Muir, Diana, "Reflections in Bullough's Pond", University Press of New England, 2000, pp. 80ff ISBN 0-87451-909-8.

Further reading

- Gentry, R. L (1998) Behavior and Ecology of the Northern Fur Seal. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[1][2][3][4]

- ^ "MarineBio Search ~ MarineBio Conservation Society". 6 April 2017.

- ^ "MarineBio Search ~ MarineBio Conservation Society". 6 April 2017.

- ^ "MarineBio Search ~ MarineBio Conservation Society". 6 April 2017.

- ^ "Northern Fur Seal | the Marine Mammal Center".