Cuadrángulo del Lago Ismenius

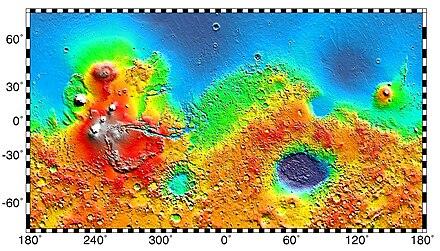

Mapa del cuadrángulo del lago Ismenius a partir de los datos del altímetro láser Mars Orbiter (MOLA). Las elevaciones más altas están en rojo y las más bajas en azul. | |

| Coordenadas | 47°30′N 330°00′O / 47.5, -330 |

|---|---|

El cuadrángulo Ismenius Lacus es uno de una serie de 30 mapas cuadrangulares de Marte utilizados por el Programa de Investigación de Astrogeología del Servicio Geológico de los Estados Unidos (USGS) . El cuadrángulo está ubicado en la porción noroeste del hemisferio oriental de Marte y cubre de 0° a 60° de longitud este (300° a 360° de longitud oeste) y de 30° a 65° de latitud norte. El cuadrángulo utiliza una proyección cónica conforme de Lambert a una escala nominal de 1:5 000 000 (1:5M). El cuadrángulo Ismenius Lacus también se conoce como MC-5 (Mars Chart-5). [1] Los límites sur y norte del cuadrángulo Ismenius Lacus tienen aproximadamente 3065 km (1905 mi) y 1500 km (930 mi) de ancho, respectivamente. La distancia de norte a sur es de unos 2050 km (1270 mi) (un poco menos que la longitud de Groenlandia). [2] El cuadrángulo cubre un área aproximada de 4,9 millones de kilómetros cuadrados, o un poco más del 3% de la superficie de Marte. [3] El cuadrángulo de Ismenius Lacus contiene partes de Acidalia Planitia , Arabia Terra , Vastitas Borealis y Terra Sabaea . [4]

El cuadrángulo de Ismenius Lacus contiene Deuteronilus Mensae y Protonilus Mensae , dos lugares que son de especial interés para los científicos. Contienen evidencia de actividad glacial presente y pasada. También tienen un paisaje único en Marte, llamado terreno erosionado . El cráter más grande del área es el cráter Lyot , que contiene canales probablemente tallados por agua líquida. [5] [6]

Origen de los nombres

Ismenius Lacus es el nombre de una formación de albedo telescópica situada a 40° N y 30° E en Marte. El término en latín significa lago Ismenio y se refiere al manantial Ismenio cerca de Tebas en Grecia, donde Cadmo mató al dragón guardián. Cadmo fue el legendario fundador de Tebas y había ido al manantial para buscar agua. El nombre fue aprobado por la Unión Astronómica Internacional (UAI) en 1958. [7]

En esta región parecía haber un gran canal llamado Nilo. Desde 1881-1882 se dividió en otros canales, algunos de los cuales se denominaron Nilosyrtis, Protonilus (primer Nilo) y Deuteronilus (segundo Nilo). [8]

Fisiografía y geología

En el este del lago Ismenius, se encuentra Mamers Valles , un canal de salida gigante.

- Vista panorámica de Mamers Vallis con acantilados, tal como la vio HiRISE

- Acantilado liso de Mamers Valles. Nótese la ausencia de rocas. Es posible que gran parte de la superficie haya sido arrastrada por el viento o haya caído del cielo (en forma de escarcha sucia). Imagen de HiRISE.

- Depósito estratificado en Mamers Valles, visto por HiRISE

El canal que se muestra a continuación recorre una gran distancia y tiene ramificaciones. Termina en una depresión que puede haber sido un lago en algún momento. La primera imagen es un gran angular, tomada con CTX; mientras que la segunda es un primer plano tomado con HiRISE. [9]

- Canales de Arabia vistos por CTX Este canal serpentea a lo largo de una buena distancia y tiene ramificaciones. Termina en una depresión que en algún momento pudo haber sido un lago.

- Canal en Arabia, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el programa HiWish . Esta es una ampliación de la imagen anterior que se tomó con CTX para ofrecer una vista más amplia.

- Canal dentro de un canal más grande, como se ve en el programa HiRISE de HiWish. La existencia del canal más pequeño sugiere que el agua pasó por la región al menos dos veces en el pasado.

- Primer plano de un canal dentro de un canal más grande, como lo vio HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish. La existencia de un canal más pequeño sugiere que el agua atravesó la región al menos dos veces en el pasado. El recuadro negro representa el tamaño de un campo de fútbol. Algunas partes de la superficie serían difíciles de transitar debido a las numerosas colinas y depresiones pequeñas.

- Sistema de canales que atraviesa parte de un cráter, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Canal que atraviesa el borde de un cráter, visto por HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Sistema de canales que atraviesa parte de un cráter, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish. Nota: esta es una ampliación de una imagen anterior.

- Canal que atraviesa parte de un cráter, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el programa HiWish. La flecha muestra un cráter erosionado por el canal. Nota: esta es una ampliación de una imagen anterior.

- Canales, como los ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Meandro en un canal, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el programa HiWish. Los meandros se forman comúnmente en sistemas fluviales antiguos cuando el agua se mueve lentamente.

- Vista amplia de canales, como los ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Vista cercana del canal, como lo ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Canal que ha atravesado el borde de un cráter, como lo ve HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Vista amplia de canales, como los ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Vista amplia de canales, como los ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Canal, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el programa HiWish

- Vista amplia de canales, como los ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Canal con valle colgante, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el programa HiWish

- Vista amplia de canales, como los ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Vista amplia de canales, como los ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Canal, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el programa HiWish

- Canales, como los ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Canales, como los ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Canales, tal como los ve HiRISE con el programa HiWish. Algunas partes de la imagen muestran el manto y otras no muestran que el manto cubra la superficie.

- Posible canal invertido, como lo ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

Cráter Lyot

Las llanuras del norte son generalmente planas y lisas con pocos cráteres. Sin embargo, algunos cráteres grandes se destacan. El cráter de impacto gigante , Lyot, es fácil de ver en la parte norte de Ismenius Lacus. [10] El cráter Lyot es el punto más profundo del hemisferio norte de Marte. [11] Una imagen a continuación de las dunas del cráter Lyot muestra una variedad de formas interesantes: dunas oscuras, depósitos de tonos claros y rastros de remolinos de polvo . Los remolinos de polvo, que se parecen a tornados en miniatura, crean los rastros al eliminar un depósito delgado pero brillante de polvo para revelar la superficie subyacente más oscura. Se cree ampliamente que los depósitos de tonos claros contienen minerales formados en agua. Una investigación, publicada en junio de 2010, describió evidencia de agua líquida en el cráter Lyot en el pasado. [5] [6]

Se han encontrado muchos canales cerca del cráter Lyot. Una investigación, publicada en 2017, concluyó que los canales se formaron a partir del agua liberada cuando el material eyectado caliente aterrizó en una capa de hielo de entre 20 y 300 metros de espesor. Los cálculos sugieren que el material eyectado habría tenido una temperatura de al menos 250 grados Fahrenheit. Los valles parecen comenzar debajo del material eyectado cerca del borde exterior del mismo. Una evidencia de esta idea es que hay pocos cráteres secundarios cerca. Pocos cráteres secundarios se formaron porque la mayoría aterrizó en el hielo y no afectó al suelo de abajo. El hielo se acumuló en el área cuando el clima era diferente. La inclinación u oblicuidad del eje cambia con frecuencia. Durante los períodos de mayor inclinación, el hielo de los polos se redistribuye a las latitudes medias. La existencia de estos canales es inusual porque, aunque Marte solía tener agua en ríos, lagos y un océano, estas características se han datado en los períodos Noéico y Hespériense , hace 4 a 3 mil millones de años. [12] [13] [14]

- Barrancos del cráter Lyot, vistos por HiRISE

- Canal del cráter Lyot, visto por CTX . Se han visto canales tallados por el agua en el cráter Lyot; la línea curva puede ser uno de ellos. Haga clic en la imagen para verla mejor.

- Canales en el cráter Lyot, vistos por HiRISE

- Vista panorámica de los canales del cráter Lyot, tal como los vio HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Vista cercana de los canales en el cráter Lyot, como los vio HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Vista cercana de los canales en el cráter Lyot, como los vio HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Canal, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el programa HiWish

- Canal con ramificaciones en el cráter Lyot, visto por HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Dunas del cráter Lyot , vistas por HiRISE. Haga clic en la imagen para ver los depósitos de tonos claros y las huellas de los remolinos de polvo.

- Canal, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el programa HiWish

- Canal, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el programa HiWish

Otros cráteres

Los cráteres de impacto suelen tener un borde con material eyectado a su alrededor; en cambio, los cráteres volcánicos no suelen tener borde ni depósitos de material eyectado. A medida que los cráteres se hacen más grandes (superiores a 10 km de diámetro), suelen tener un pico central. [15] El pico se produce por un rebote del suelo del cráter tras el impacto. [16] A veces, los cráteres muestran capas en sus paredes. Dado que la colisión que produce un cráter es como una potente explosión, las rocas de las profundidades subterráneas son arrojadas a la superficie. Por lo tanto, los cráteres son útiles para mostrarnos lo que se encuentra en las profundidades de la superficie.

- Posibles cráteres secundarios expandidos, como los que se observaron con HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish. Estos cráteres pueden haberse vuelto mucho más anchos, a medida que el hielo se desprendía del suelo alrededor de los bordes. [17] [18]

- Cráter reciente, tal como lo vio HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish. Se trata de un cráter joven porque se pueden ver fácilmente el borde y el material expulsado. Aún no se han erosionado.

- Cráter reciente con eyecciones bien definidas

- Cráter de impacto que puede haberse formado en un terreno rico en hielo, como lo vio HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Cráter de impacto que puede haberse formado en un terreno rico en hielo, como se vio con HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish. Nótese que el material eyectado parece estar más bajo que el entorno. El material eyectado caliente puede haber provocado que parte del hielo desapareciera, lo que redujo el nivel del material eyectado.

- Cráter de pedestal, visto por HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish. Los materiales expulsados del cráter protegieron el terreno subyacente de la erosión.

- Cráter con pedestal, tal como lo vio HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish. Mesa en el fondo del cráter formada después del cráter.

- Cráter con un banco, visto por HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Valles en el manto de material eyectado del cráter Cerulli , vistos por HiRISE

- Canales del cráter Cerulli , vistos por THEMIS. Los canales se encuentran en el borde norte interior del cráter.

- El cráter Cerulli, visto por HiRISE

- Drenaje del cráter Semeykin , visto por THEMIS . Haga clic en la imagen para ver los detalles del hermoso sistema de drenaje.

- Lado occidental del cráter Focas , visto por la cámara CTX (a bordo del Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter )

- Pequeños canales en el cráter Focus, vistos por la cámara CTX (a bordo del Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Nótese que esta es una ampliación de la imagen anterior del cráter Focus tomada por CTX.

- Lado oriental del cráter Quenisset , visto por la cámara CTX (en el Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter)

- Borde noreste del cráter Quenisset, visto por la cámara CTX (a bordo del Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Nota: esta es una ampliación de la imagen anterior del cráter Quenisset. Las flechas indican los glaciares antiguos.

- Lado oeste del cráter Sinton , visto por la cámara CTX (en el Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter )

- Canales al sur del cráter Sinton, vistos por la cámara CTX (a bordo del Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Se formaron cuando se produjo el impacto en un terreno rico en hielo. Nota: esta es una ampliación de la imagen anterior del lado oeste de Sinton.

- Glaciar antiguo al norte del cráter Sinton, visto por la cámara CTX (a bordo del Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Es uno de los muchos glaciares de la región. Nota: esta es una ampliación de una imagen anterior del lado oeste de Sinton.

- Mapa MOLA que muestra el cráter Rudaux y otros cráteres cercanos. Los colores indican las elevaciones.

- Borde oeste del cráter Rudaux, visto por la cámara CTX (en el Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter)

- Grupo de capas en un cráter, como se ve con HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Vista panorámica de cráteres con depósitos extraños, tal como los vio HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Vista cercana de un cráter con un extraño depósito estratificado, como lo vio HiRISE

- Vista cercana de un cráter con un extraño depósito estratificado

- Doble cráter. El recuadro muestra el tamaño de un campo de fútbol. El objeto se partió en dos justo antes de impactar contra la superficie.

- Cráter con meseta. Primero se formó el cráter. Luego se depositó material en la zona. Ese material se erosionó por todas partes, excepto en este cráter.

Terreno accidentado

El cuadrángulo de Ismenius Lacus contiene varias características interesantes, como el terreno erosionado , partes del cual se encuentran en Deuteronilus Mensae y Protonilus Mensae. El terreno erosionado contiene tierras bajas lisas y planas junto con acantilados escarpados. Las escarpaduras o acantilados suelen tener entre 1 y 2 km de altura. Los canales de la zona tienen suelos anchos y planos y paredes escarpadas. Hay muchos montículos y mesetas . En el terreno erosionado, la tierra parece pasar de valles estrechos y rectos a mesetas aisladas. [19] La mayoría de las mesetas están rodeadas de formas que han recibido una variedad de nombres: delantales circunmesa, delantales de escombros, glaciares de roca y delantales de escombros lobulados . [20] Al principio parecían parecerse a los glaciares de roca de la Tierra. Pero los científicos no podían estar seguros. Incluso después de que la cámara Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) del Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) tomara diversas fotografías del terreno irregular, los expertos no podían decir con certeza si el material se movía o fluía como lo haría en un depósito rico en hielo (glaciar). Finalmente, los estudios de radar con el Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter descubrieron pruebas de su verdadera naturaleza , que mostraron que contienen hielo de agua puro cubierto con una fina capa de rocas que aislaban el hielo. [21] [22]

- Terreno erosionado del lago Ismenius que muestra valles y acantilados de fondo plano. Fotografía tomada con la Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) en el Mars Global Surveyor , en el marco del Programa de focalización pública de la MOC .

- Ampliación de la fotografía de la izquierda que muestra el acantilado. Fotografía tomada con la cámara de alta resolución de Mars Global Surveyor (MGS), en el marco del Programa de Focalización Pública del MOC .

- Vista amplia de la meseta con CTX que muestra la pared del acantilado y la ubicación de la plataforma de escombros lobulada (LDA). La ubicación es el cuadrángulo del lago Ismenius.

- Ampliación de una imagen CTX anterior de la meseta. Esta imagen muestra la pared del acantilado y los detalles en el LDA. Imagen tomada con HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish. La ubicación es el cuadrángulo del lago Ismenius.

- Acantilado en terreno accidentado. La franja de color tiene aproximadamente 1 km de ancho.

- Acantilado en terreno accidentado. La franja de color tiene aproximadamente 1 km de ancho.

- Vista amplia de CTX que muestra mesetas y cerros con plataformas de escombros lobulados y relleno de valle lineal a su alrededor. La ubicación es el cuadrángulo del lago Ismenius.

- Primer plano del relleno de valle lineal (LVF), tal como se ve con HiRISE en el programa HiWish. Nota: esta es una ampliación de la imagen CTX anterior.

- Vista cercana del relleno del valle lineal (LVF). La imagen tiene aproximadamente 1 km de ancho.

- Ejemplo de terreno irregular, tal como lo ve HiRISE con el programa HiWish. El terreno irregular contiene muchos valles amplios y planos.

- Valle de fondo plano en terreno accidentado, como se ve con HiRISE en el programa HiWish

- Canalización de fondo plano en terreno accidentado, como se ve en HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

Glaciares

Los glaciares formaron gran parte de la superficie observable en grandes áreas de Marte. Se cree que gran parte del área en latitudes altas, especialmente el cuadrángulo Ismenius Lacus, aún contiene enormes cantidades de hielo de agua. [16] [21] [23] En marzo de 2010, los científicos publicaron los resultados de un estudio de radar de un área llamada Deuteronilus Mensae que encontró evidencia generalizada de hielo debajo de unos pocos metros de escombros de roca. [24] El hielo probablemente se depositó como nevada durante un clima anterior cuando los polos estaban más inclinados. [25] Sería difícil hacer una caminata en el terreno erosionado donde los glaciares son comunes porque la superficie está plegada, picada y a menudo cubierta con estrías lineales. [26] Las estrías muestran la dirección del movimiento. Gran parte de esta textura rugosa se debe a la sublimación del hielo enterrado. El hielo se convierte directamente en gas (este proceso se llama sublimación) y deja atrás un espacio vacío. El material superpuesto luego colapsa en el vacío. [27] Los glaciares no son hielo puro; contienen tierra y rocas. A veces, vierten su carga de materiales en crestas. Estas crestas se llaman morrenas . Algunos lugares en Marte tienen grupos de crestas que están retorcidas; esto puede haberse debido a un mayor movimiento después de que se formaron las crestas. A veces, trozos de hielo caen del glaciar y quedan enterrados en la superficie terrestre. Cuando se derriten, queda un agujero más o menos redondo. [28] En la Tierra llamamos a estas características calderas o agujeros de caldera. El parque Mendon Ponds en el norte del estado de Nueva York ha preservado varias de estas calderas. La imagen de HiRISE a continuación muestra posibles calderas en el cráter Moreux.

- La flecha de la imagen de la izquierda señala un posible valle tallado por un glaciar. La imagen de la derecha muestra el valle muy ampliado en una imagen del Mars Global Surveyor.

- Morrenas y pozos de agua del cráter Moreux , vistos por HIRISE

- Los valles de Clanis e Hypsas, vistos por HiRISE. Las crestas probablemente se deban al flujo glacial, por lo que el hielo de agua se encuentra debajo de una fina capa de rocas.

- El glaciar se aleja del valle, como lo ve HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- El glaciar Pie de Elefante del lago Romer en el Ártico de la Tierra, visto por el satélite Landsat 8. Esta imagen muestra varios glaciares que tienen la misma forma que muchas características de Marte que se cree que también son glaciares.

- Glaciar saliendo del valle, como lo ve HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish. La ubicación es el borde del cráter Moreux .

- Flujo, como lo ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Flujo, como lo ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Glaciar afluente , visto por HiRISE

- Los glaciares se mueven formando valles en una meseta, como se ve en HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Dos glaciares interactuando, como se ve en el programa HiRISE de HiWish. El de la izquierda es más reciente y fluye sobre el otro.

- Glaciar interactuando con un obstáculo, como lo ve HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Glaciar que fluye desde un valle, visto por HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Imagen de contexto CTX que muestra la ubicación de la siguiente imagen HiRISE (recuadro con la letra A)

- Posible morrena en el extremo de un glaciar anterior sobre un montículo en Deuteronilus Mensae , como se ve en HiRISE, en el marco del programa HiWish. La ubicación de esta imagen es el recuadro con la etiqueta A en la imagen anterior.

- Cresta que probablemente pertenece a un antiguo glaciar, como se ve con HiRISE en el programa HiWish

- Valle de relleno lineal de Coloe Fossae , visto desde HiRISE. La barra de escala tiene 500 metros de largo.

- Relleno de valle lineal, tal como lo ve HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish

- Vista cercana del relleno del valle lineal, como lo ve HiRISE bajo el programa HiWish

- Vista cercana y en color del relleno de valle lineal, como lo ve HiRISE con el programa HiWish

- Relleno de valle lineal en valle, como se ve con HiRISE en el programa HiWish

- Relleno lineal de valles en valles, como se observa con HiRISE en el programa HiWish. El flujo lineal de valles es hielo cubierto por escombros.

- Vista cercana y en color del relleno de valle lineal, como lo ve HiRISE con el programa HiWish

- Relleno lineal de valles en valles, como se observa con HiRISE en el programa HiWish. El flujo lineal de valles es hielo cubierto por escombros.

- Vista cercana del relleno lineal del valle (LVF, por sus siglas en inglés), como se ve con HiRISE en el programa HiWish. El flujo lineal del valle es hielo cubierto por escombros. La imagen tiene aproximadamente 1 km de ancho.

- Vista cercana del relleno lineal del valle (LVF) en el valle, como se ve con HiRISE en el programa HiWish. El flujo lineal del valle es hielo cubierto por escombros.

- Vista cercana del relleno lineal del valle (LVF) en el valle, como se ve con HiRISE en el programa HiWish. El flujo lineal del valle es hielo cubierto por escombros.

- Relleno lineal de valles en valles, como se observa con HiRISE en el programa HiWish. El flujo lineal de valles es hielo cubierto por escombros.

- Vista cercana del relleno lineal del valle (LVF, por sus siglas en inglés), como se ve con HiRISE en el programa HiWish. El flujo lineal del valle es hielo cubierto por escombros. La imagen tiene aproximadamente 1 km de ancho.

- Lugar donde comienza una plataforma de escombros lobulada. Nótese las rayas que indican movimiento.

- Probable glaciar visto por HiRISE en el marco del programa HiWish. Los estudios de radar han descubierto que está formado casi en su totalidad por hielo puro. Parece estar moviéndose desde el terreno elevado (una meseta) a la derecha.

- Mesa en el cuadrángulo de Ismenius Lacus, vista por CTX. La mesa está erosionada por varios glaciares. Uno de los glaciares se ve con mayor detalle en las dos siguientes imágenes de HiRISE.

- Glacier as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. Area in rectangle is enlarged in the next photo. Zone of accumulation of snow at the top. Glacier is moving down valley, then spreading out on plain. Evidence for flow comes from the many lines on surface. Location is in Protonilus Mensae in Ismenius Lacus quadrangle.

- Enlargement of area in rectangle of the previous image. On Earth the ridge would be called the terminal moraine of an alpine glacier. Picture taken with HiRISE under the HiWish program.

- Flow ridges from a previous glacier, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Remains of glaciers, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program

- Remains of a glacier after ice has disappeared, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Arrows point to drumlin-like shapes that were probably formed under a glacier, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

- Lobate debris aprons (LDAs) around a mesa, as seen by CTX Mesa and LDAs are labeled so one can see their relationship. Radar studies have determined that LDAs contain ice; therefore these can be important for future colonists of Mars. Location is Ismenius Lacus quadrangle.

- Close-up of lobate debris apron (LDA), as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide CTX view of mesa showing lobate debris apron (LDA) and lineated valley fill. Both are believed to be debris-covered glaciers. Location is Ismenius Lacus quadrangle.

- Close-up of lobate debris apron from the previous CTX image of a mesa. Image shows open-cell brain terrain and closed-cell brain terrain, which is more common. Open-cell brain terrain is thought to hold a core of ice. Image is from HiRISE under HiWish program.

- Lobate debris apron around mesa, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of lobate debris apron around mesa, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Brain terrain is visible.

- Glaciers moving in two different valleys, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of flow moving down valley, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of part of glacier, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Box shows size of football field.

- Flow and mantle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close, color view of flow, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of tongue-shaped glacier and lineated valley fill, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Tongue-shaped glacier, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of the previous image.

- Close view of tongue-shaped glacier, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Surface is broken up into cubes.

Much of the Martian surface is covered with a thick ice-rich, mantle layer that has fallen from the sky a number of times in the past.[29][30][31]

- Close view of mantle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrows show craters along edge which highlight the thickness of mantle.

- Close view that displays the thickness of the mantle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Mantle and flow, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. A part of the image showing the mantle is enlarged in the next image.

- Mantle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of mantle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of mantle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Color view of mantle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Some parts of the image are covered with mantle; other parts are not.

- Mantle layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Mantle layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Mantle layers seem to be forming a group of dipping layers.

Climate change caused ice-rich features

Many features on Mars, especially ones found in the Ismenius Lacus quadrangle, are believed to contain large amounts of ice. The most popular model for the origin of the ice is climate change from large changes in the tilt of the planet's rotational axis. At times the tilt has even been greater than 80 degrees[32][33] Large changes in the tilt explains many ice-rich features on Mars.

Studies have shown that when the tilt of Mars reaches 45 degrees from its current 25 degrees, ice is no longer stable at the poles.[34] Furthermore, at this high tilt, stores of solid carbon dioxide (dry ice) sublimate, thereby increasing the atmospheric pressure. This increased pressure allows more dust to be held in the atmosphere. Moisture in the atmosphere will fall as snow or as ice frozen onto dust grains. Calculations suggest this material will concentrate in the mid-latitudes.[35][36] General circulation models of the Martian atmosphere predict accumulations of ice-rich dust in the same areas where ice-rich features are found.[33] When the tilt begins to return to lower values, the ice sublimates (turns directly to a gas) and leaves behind a lag of dust.[37][38] The lag deposit caps the underlying material so with each cycle of high tilt levels, some ice-rich mantle remains behind.[39] Note that the smooth surface mantle layer probably represents only relative recent material.

Upper Plains Unit

- Wide view showing contact between upper plains unit lower part of picture and a lower unit, as seen by CTX

- Contact, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Upper plains unit on the left is breaking up. A lower unit exists on the right side of picture.

- Close view of contact, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Picture shows details of how upper plains material is breaking. The formation of many fractures seems to precede the break up.

- Wide view of upper plains unit eroding into hollows, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Parts of this image are enlarged in following images.

- Close view of upper plain unit eroding into hollows, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Breakup begins with cracks on the surface that expand as more and more ice disappears from the ground.

- Close view of hollows, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Remnants of a 50–100 meter thick mantling, called the Upper Plains Unit, has been discovered in the mid-latitudes of Mars. First investigated in the Deuteronilus Mensae region, but it occurs in other places as well. The remnants consist of sets of dipping layers in craters and along mesas.[40][41] Sets of dipping layers may be of various sizes and shapes—some look like Aztec pyramids from Central America.

- Groups of dipping layers near mounds, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of dipping layers along mesa walls, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of dipping layers along a mesa wall, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Dipping layers in a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Group of small sets of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layered features in crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layered feature in Red Rocks Park, Colorado. This has a different origin than ones on Mars, but it has a similar shape. Features in Red Rocks region were caused by uplift of mountains.

- Dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layered structures, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layered structures, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layered features, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layered features in channels and depressions, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrows point to some of the layered features.

- Wide view of dipping layers, upper plains unit, and brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Parts of this picture are enlarged in other images.

- Dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. This is an enlargement of a previous image.

- Dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Brain terrain is also visible in the image.

- Wide view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Gullies are also visible at the bottom of the image.

This unit also degrades into brain terrain. Brain terrain is a region of maze-like ridges 3–5 meters high. Some ridges may consist of an ice core, so they may be sources of water for future colonists.

- Brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layered features, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. On the right side of picture a small region of ribbed upper plains material is changing into brain terrain.

- Layered features and brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. The upper plains unit often changes into brain terrain.

- Brain terrain being formed from a thicker layer, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrows show the thicker unit breaking up into small cells.

- Possible glacier surrounded by brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Brain terrain is forming from the breakdown of upper plains unit, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrow points to a place where fractures are forming that will turn into brain terrain.

- Brain terrain is forming from the breakdown of upper plains unit, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrow points to a place where fractures are forming that will turn into brain terrain.

- Wide view of brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of previous image using HiView.

- Brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of a previous image using HiView.

- Brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of a previous image using HiView. Arrows indicate spots where brain terrain is beginning to form.

- Brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of a previous image using HiView. Arrows indicate spots where brain terrain is beginning to form.

- Brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of a previous image using HiView.

- Wide view of brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of the previous image using HiView.

- Brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of a previous image using HiView.

- Brain terrain with a view from the side, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrow shows where a side view of the brain terrain is visible.

- Open and closed brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Open and closed brain terrain with labels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Open and closed brain terrain with labels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Brain terrain being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrows point to locations where the brain terrain is starting to form.

- Brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Some regions of the upper plains unit display large fractures and troughs with raised rims; such regions are called ribbed upper plains. Fractures are believed to have started with small cracks from stresses. Stress is suggested to initiate the fracture process since ribbed upper plains are common when debris aprons come together or near the edge of debris aprons—such sites would generate compressional stresses. Cracks exposed more surfaces, and consequently more ice in the material sublimates into the planet's thin atmosphere. Eventually, small cracks become large canyons or troughs.

- Well developed ribbed upper plains material. These start with small cracks that expand as ice sublimates from the surfaces of the crack. Picture was taken with HiRISE under HiWish program

- Small and large cracks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program The small cracks to the left will enlarge to become much larger dues to sublimation of ground ice. A crack exposes more surface area, hence greatly increases sublimation in the thin Martian air.

- Close-up of canyons from previous image, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- View of stress cracks and larger cracks that have been enlarged by sublimation (ice changing directly into gas). This may be the start of ribbed terrain.

- Evolution of ribbed terrain from stress cracks—cracks to the left eventually will enlarge and become ribbed terrain toward the right side of picture, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Also, Ribbed Upper plains material is visible in the upper right of the picture. It is forming from the upper plains unit, and in turn is being eroded into brain terrain.

- Wide view of ribbed terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of ribbed terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view showing ribbed terrain and brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Ribbed terrain being formed from upper plains unit, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Formation begins with cracks that enhance sublimation. Box shows the size of football field.

- Cracks forming on surface and then breaking down, as ice is removed. Picture taken with HiRISE under HiWish program.

- Surface breaking down, as ice is removed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Box shows size of football field.

- Wide view of terrain caused by ice leaving the ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of terrain caused by ice leaving the ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of terrain caused by ice leaving the ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of terrain caused by ice leaving the ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of terrain caused by ice leaving the ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Box shows size of football field.

- Wide view of upper plains with many hollows

- Close view of upper plains unit showing hollows--where ice left the ground. Picture is about 1 Km across. This is part of an image named HiRISE picture of the day for October 21, 2024.

- Close view of upper plains unit showing hollows--where ice left the ground. Picture is about 1 Km across. This is part of an image named HiRISE picture of the day for October 21, 2024.

- Close view of upper plains unit showing hollows--where ice left the ground. Picture is about 1 Km across. This is part of an image named HiRISE picture of the day for October 21, 2024.

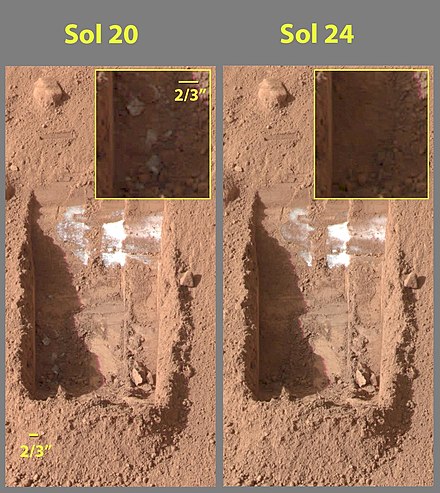

Small cracks often contain small pits and chains of pits; these are thought to be from sublimation of ice in the ground.[42][43] Large areas of the Martian surface are loaded with ice that is protected by a meters thick layer of dust and other material. However, if cracks appear, a fresh surface will expose ice to the thin atmosphere.[44][45] In a short time, the ice will disappear into the cold, thin atmosphere in a process called sublimation. Dry ice behaves in a similar fashion on the Earth. On Mars sublimation has been observed when the Phoenix lander uncovered chunks of ice that disappeared in a few days.[46][47] In addition, HiRISE has seen fresh craters with ice at the bottom. After a time, HiRISE saw the ice deposit disappear.[48]

- Die-sized clumps of bright material in the enlarged "Dodo-Goldilocks" trench vanished over the course of four days, implying that they were composed of ice which sublimated following exposure.[47][49]

- Color versions of the photos showing ice sublimation, with the lower left corner of the trench enlarged in the insets in the upper right of the images

The upper plains unit is thought to have fallen from the sky. It drapes various surfaces, as if it fell evenly. As is the case for other mantle deposits, the upper plains unit has layers, is fine-grained, and is ice-rich. It is widespread; it does not seem to have a point source. The surface appearance of some regions of Mars is due to how this unit has degraded. It is a major cause of the surface appearance of lobate debris aprons.[43] The layering of the upper plains mantling unit and other mantling units are believed to be caused by major changes in the planet's climate. Models predict that the obliquity or tilt of the rotational axis has varied from its present 25 degrees to maybe over 80 degrees over geological time. Periods of high tilt will cause the ice in the polar caps to be redistributed and change the amount of dust in the atmosphere.[50][51][52]

Dipping layers

In many locations around Mars are features that have been called "dipping layers" These features are groups of layers in protected place like inside of craters or against slopes. Although they once covered a wide area, today they exist only in certain spots because erosion has removed most of the material. Several ideas have been advanced for how they were formed.[53] The material that formed them may have dropped from the sky as ice-rich dust.[54] [55] [56] Another idea for their origin was presented at 55th LPSC (2024) by an international team of researchers. They suggest that the layers are from past ice sheets.[57]

- Wide view of dipping layers, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. The dark strip is where a computer problem is preventing the gathering of data.

- Group of dipping layers. Each layer represents a change in the Martian climate.

- Remaining parts of a group of dipping layers. Erosion has removed most of the material.

- Close view of dipping layers that show the thin nature of the layers

- Several sets of dipping layers

- Close view of dipping layers Each layer was deposited when the climate changed. These layers only appear in protected areas.

Deltas

Researchers have found a number of examples of deltas that formed in Martian lakes. Deltas are major signs that Mars once had a lot of water because deltas usually require deep water over a long period of time to form. In addition, the water level needs to be stable to keep sediment from washing away. Deltas have been found over a wide geographical range. Below, is a pictures of a one in the Ismenius Lacus quadrangle.[58]

- Delta in Ismenius Lacus quadrangle, as seen by THEMIS

Pits and cracks

Some places in the Ismenius Lacus quadrangle display large numbers of cracks and pits. It is widely believed that these are the result of ground ice sublimating (changing directly from a solid to a gas). After the ice leaves, the ground collapses in the shape of pits and cracks. The pits may come first. When enough pits form, they unite to form cracks.[59]

- Coloe Fossae Pits, as seen by HiRISE. Pits are believed to result from escaping water.

- CTX Image in Protonilus Mensae, showing location of next image

- Pits in Protonilus Mensae, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program.

- Close-up of pits, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. Resolution is about 30 cm, so one could see a kitchen table if it were in the picture.

- Close-up of patterned ground in a crater deposit, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. Resolution is about 30 cm, so one could see a kitchen table if it were in the picture.

- Close-up of pits forming along the edges of polygons in patterned ground, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. Resolution is about 30 cm, so one could see a kitchen table if it were in the picture.

- Wide view of lines of pits, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program

- Close view of lines of pits, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program Box shows size of football field. Pits may be up to around 50 meters across.

- Close view of lines of pits, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program

- Curved ridges as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program

- Close view of pits and polygons, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program. Pits seem to occur in low spots between polygons.

- Wide view of mesas and pits, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program

- Close view of pits and brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program

- Close view of pits, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program

Mesas formed by ground collapse

- Group of mesas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Oval box contains mesas that may have moved apart.

- Enlarged view of a group of mesas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. One surface is forming square shapes.

- Mesas breaking up forming straight edges, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Volcanoes under ice

There is evidence that volcanoes sometimes erupt under ice, as they do on Earth at times. What seems to happen it that much ice melts, the water escapes, and then the surface cracks and collapses.[60] These exhibit concentric fractures and large pieces of ground that seemed to have been pulled apart. Sites like this may have recently had held liquid water, hence they may be fruitful places to search for evidence of life.[61][62]

- Large group of concentric cracks, as seen by HiRISE, under HiWish program Location is Ismenius Lacus quadrangle. Cracks were formed by a volcano under ice.[61]

- Tilted layers formed when ground collapsed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Tilted layers formed from ground collapse, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Mesas breaking up into blocks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Collapse features from volcano erupting under ice

- Close view of collapse features from volcano erupting under ice

- Close view of collapse features from volcano erupting under ice

- Close view of collapse features from volcano erupting under ice

- Wide view of cracked surface and collapse depressions, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Depression forming from a possible subsurface loss of material, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Exhumed craters

Some features on Mars seem to be in the process of being uncovered. So, the thought is that they formed, were covered over, and now are being exhumed as material is being eroded. These features are quite noticeable with craters. When a crater forms, it will destroy what is under it and leave a rim and ejecta. In the example below, only part of the crater is visible. if the crater came after the layered feature, it would have removed part of the feature.

- Wide view of exhumed craters, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of exhumed crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. This crater is and was under a set of dipping layers.

Fractures forming blocks

In places large fractures break up surfaces. Sometimes straight edges are formed and large cubes are created by the fractures.

- Wide view of mesas that are forming fractures, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Enlarged view of a part of previous image, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. The rectangle represents the size of a football field.

- Close-up of blocks being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close-up of blocks being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. The rectangle represents the size of a football field, so blocks are the size of buildings.

- Close-up of blocks being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Many long fractures are visible on the surface.

- Surface breaking up, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Near the top the surface is eroding into brain terrain.

- Wide view showing light-toned feature that is breaking into blocks, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view showing blocks being formed, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of the previous image. Box represents the size of a football field.

- Color view of rocks breaking apart, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Polygonal patterned ground

Polygonal, patterned ground is quite common in some regions of Mars.[63][64][65][66][67][68][69] It is commonly believed to be caused by the sublimation of ice from the ground. Sublimation is the direct change of solid ice to a gas. This is similar to what happens to dry ice on the Earth. Places on Mars that display polygonal ground may indicate where future colonists can find water ice. Patterned ground forms in a mantle layer, called latitude dependent mantle, that fell from the sky when the climate was different.[29][30][70][71]

- High-center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Image is of the top of a debris apron in Deuteronilus Mensae.

- Close-up of field of high center polygons with scale, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: the black box is the size of a football field.

- Close-up of high center polygons seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: the black box is the size of a football field.

- Close-up of high center polygons seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Troughs between polygons are easily visible in this view.

- High center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Low center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of high center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of high center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Centers of polygons are labeled.

- Cracked surface and low center polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Large polygons, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Dunes

Sand dunes have been found in many places on Mars. The presence of dunes shows that the planet has an atmosphere with wind, for dunes require wind to pile up the sand. Most dunes on Mars are black because of the weathering of the volcanic rock basalt.[72][73] Black sand can be found on Earth on Hawaii and on some tropical South Pacific islands.[74]Sand is common on Mars due to the old age of the surface that has allowed rocks to erode into sand. Dunes on Mars have been observed to move many meters.[75][76]Some dunes move along. In this process, sand moves up the windward side and then falls down the leeward side of the dune, thus caused the dune to go toward the leeward side (or slip face).[77]When images are enlarged, some dunes on Mars display ripples on their surfaces.[78] These are caused by sand grains rolling and bouncing up the windward surface of a dune. The bouncing grains tend to land on the windward side of each ripple. The grains do not bounce very high so it does not take much to stop them.

- Wide view of dunes in Moreux Crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Enlarged view of dunes on the bottom of the previous image, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of one large dune from the same location, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of white spot among the dark dunes showing ripples and streaks

- Wide view of a field of dunes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close, color view of dunes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close, color view of dunes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close, color view of dunes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Ocean

Many researchers have suggested that Mars once had a great ocean in the north.[79][80][81][82][83][84][85] Much evidence for this ocean has been gathered over several decades. New evidence was published in May 2016. A large team of scientists described how some of the surface in Ismenius Lacus quadrangle was altered by two tsunamis. The tsunamis were caused by asteroids striking the ocean. Both were thought to have been strong enough to create 30 km diameter craters. The first tsunami picked up and carried boulders the size of cars or small houses. The backwash from the wave formed channels by rearranging the boulders. The second came in when the ocean was 300 m lower. The second carried a great deal of ice which was dropped in valleys. Calculations show that the average height of the waves would have been 50 m, but the heights would vary from 10 m to 120 m. Numerical simulations show that in this particular part of the ocean two impact craters of the size of 30 km in diameter would form every 30 million years. The implication here is that a great northern ocean may have existed for millions of years. One argument against an ocean has been the lack of shoreline features. These features may have been washed away by these tsunami events. The parts of Mars studied in this research are Chryse Planitia and northwestern Arabia Terra. These tsunamis affected some surfaces in the Ismenius Lacus quadrangle and in the Mare Acidalium quadrangle.[86][87][88][89]

- Channels made by the backwash from tsunamis, as seen by HiRISE. Tsunamis were probably caused by asteroids striking the ocean.

- Channels that may have been made by the backwash of tsunamis in an ocean. Image is from HiRISE under the HiWish program.

- Possible backwash channels that may have been created by a tsunami, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Boulders that were picked up, carried, and dropped by tsunamis, as seen by HiRISE. Tsunamis were probably caused by asteroids striking ocean. Boulders are between the size of cars and houses.

- Streamlined promontory eroded by tsunami, as seen by HiRISE. Tsunamis were probably caused by asteroids striking ocean.

- Concentric bands that may have been produced by the waves of a tsunami. Image is from HiRISE under the HiWish program.

Gullies

Gullies were thought for a time to have been caused by recent flows of liquid water. However, further study suggests they are formed today by chunks of dry ice moving down steep slopes.[90]

- Gullies in crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of a gully on a steep slope, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Closer view of previous image of a gully, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of channel in gully showing streamlined forms, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Gullies, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of gullies, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of gullies, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Layered features

- Layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layered mesas, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Eroded crater deposits showing layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layers in depressions, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layers, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of layers, >as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Ring mold craters

Ring Mold Craters are a kind of crater on the planet Mars, that look like the ring molds used in baking. They are believed to be caused by an impact into ice. The ice is covered by a layer of debris. They are found in parts of Mars that have buried ice. Laboratory experiments confirm that impacts into ice result in a "ring mold shape." They are also bigger than other craters in which an asteroid impacted solid rock. Impacts into ice warm the ice and cause it to flow into the ring mold shape.

However, another idea for their formation has emerged.[91]The other idea for their formation revolves around the impacting body going through layers of different densities. Later erosion could have helped shape them. It was thought that ring-mold craters could only exist in areas with large amounts of ground ice. However, with more extensive analysis of larger areas, it was found the ring mold craters are sometimes formed where there is not as much ice underground.[92] [93]

- Ring mold craters on floor of a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Ring mold craters of various sizes on floor of a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Ring-mold craters form when an impact goes through to an ice layer. The rebound forms the ring-mold shape, and then dust and debris settle on the top to insulate the ice.

- Wide view of ring-mold craters, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of ring-mold crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Group of ring-mold craters, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of ring-mold craters on floor of larger crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Ring-mold craters, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of ring-mold craters and brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of ring-mold craters and brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of ring-mold craters and brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Rectangle shows size of football field for scale.

- Ring mold crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Mounds

- Wide view of field of mounds near pedestal crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close, color view of mounds, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Row of mounds, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrows point to some of the mounds.

- Lines of mounds, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Channels

- Channels, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program

- Channels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Channels that empty into a low area that could have been a lake, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Channels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. The ends of the channels have shapes that suggest they were formed by the process of sapping.

- Channels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. These channels are in the ejecta of a crater; hence, they may have formed from warm ejecta melting ground ice.

- Channels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. These channels are near the ejecta of a crater; hence, they may have formed from warm ejecta melting ground ice.

- Channel near ejecta, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Channels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of channel, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Channels, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Dendritic channel system, as seen by HiRISE

- Channels with one leading to a lake

- Old stream bed attached to low area that was probably a lake

Landslide

- Landslide, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of landslide, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Landslides, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Type of landslide called a slump along crater wall, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Black strip is due to data not collected there.

Other images

- Wide view of terrain with hollows. The hollows were created when ice left the ground. The black strip is due to a malfunction.

- Close view of hollows

- Close view of hollows. Narrow ridges were made when hollows kept expanding.

- Close, color view of hollows. The HiView program was used in the RGB color scheme.

- Crater floor with pits, hollows, brain terrain, and ring mold craters. These are formed when ice leaves the ground.

- Wide view of hollows that formed as ice left the ground

- Close view of hollows formed when ice left the ground by sublimation

- Close view of hollows formed when ice left the ground by sublimation. The ridges were formed when hollows that were next to each other grew in size.

- Close view of hollows formed when ice left the ground

- Map of Ismenius Lacus quadrangle which is located just north of Arabia, a large bright area of Mars. It contains large amounts of ice in glaciers that surround hills.

- CTX Context image of Deuteronilus Mensae showing location of next two images

- Eroded terrain in Deuteronilus Mensae, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program

- Another view of eroded terrain in Deuteronilus Mensae, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program

- CTX context image showing location of next HiRISE image (letter B box)

- Complex surface around mound in Deuteronilus Mensae, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program. Location of this image is in the black box labeled B in the previous image.

- End of a glacier, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Surface to the right of the end moraine exhibits patterned ground which is common where ground water has frozen.

- Surface forms in Ismenius Lacus, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Hollowed out terrain in Deuteronilus Mensae, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Hollows in surface, formed as ice is removed from ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Layers visible in nearby craters, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Arrows point to layers.

- Field of pits, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Possible dike, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Pits and troughs, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Pits may have formed from water/ice leaving the ground.

- Boulders, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of contact, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of contact, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Possible mud volcanoes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of cones, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Wide view of possible pingos, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Pingos contain a core of pure ice; they would be useful for a source of water by future colonists.

- Close view of possible pingos, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Ridges, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Ridges, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Ridge, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. This ridge may be an esker.

- Wide view of honeycomb shapes and possible dikes that make an "X" shape, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

- Close view of honeycomb shapes and brain terrain, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Other Mars quadrangles

Interactive Mars map

Interactive image map of the global topography of Mars. Hover your mouse over the image to see the names of over 60 prominent geographic features, and click to link to them. Coloring of the base map indicates relative elevations, based on data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter on NASA's Mars Global Surveyor. Whites and browns indicate the highest elevations (+12 to +8 km); followed by pinks and reds (+8 to +3 km); yellow is 0 km; greens and blues are lower elevations (down to −8 km). Axes are latitude and longitude; Polar regions are noted.

Interactive image map of the global topography of Mars. Hover your mouse over the image to see the names of over 60 prominent geographic features, and click to link to them. Coloring of the base map indicates relative elevations, based on data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter on NASA's Mars Global Surveyor. Whites and browns indicate the highest elevations (+12 to +8 km); followed by pinks and reds (+8 to +3 km); yellow is 0 km; greens and blues are lower elevations (down to −8 km). Axes are latitude and longitude; Polar regions are noted. See also

References

- ^ Davies, M.E.; Batson, R.M.; Wu, S.S.C. "Geodesy and Cartography" in Kieffer, H.H.; Jakosky, B.M.; Snyder, C.W.; Matthews, M.S., Eds. Mars. University of Arizona Press: Tucson, 1992.

- ^ Distances calculated using NASA World Wind measuring tool. http://worldwind.arc.nasa.gov/ Archived 2018-01-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Approximated by integrating latitudinal strips with area of R^2 (L1-L2)(cos(A)dA) from 30° to 65° latitude; where R = 3889 km, A is latitude, and angles expressed in radians. See: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1340223/calculating-area-enclosed-by-arbitrary-polygon-on-earths-surface.

- ^ "Planetary Names: Search Results".

- ^ a b Carter, J.; Poulet, F.; Bibring, J.-P.; Murchie, S. (2010). "Detection of Hydrated Silicates in Crustal Outcrops in the Northern Plains of Mars". Science. 328 (5986): 1682–1686. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1682C. doi:10.1126/science.1189013. PMID 20576889. S2CID 7337256.

- ^ a b http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news.cfm?release=2010-209[permanent dead link]

- ^ USGS Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. Mars. http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/.

- ^ Blunck, J. 1982. Mars and its Satellites. Exposition Press. Smithtown, N.Y.

- ^ "HiRISE | A Fresh, Shallow Valley in Northern Arabia Terra (ESP_039997_2170)".

- ^ U.S. department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey, Topographic Map of the Eastern Region of Mars M 15M 0/270 2AT, 1991

- ^ "Mars: What We Know About the Red Planet". Space.com. October 2021.

- ^ Weiss, David K. (2017). "Extensive Amazonian-aged fluvial channels on Mars: Evaluating the role of Lyot crater in their formation". Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (11): 5336–5344. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..44.5336W. doi:10.1002/2017GL073821. S2CID 27711077.

- ^ Weiss, D.; et al. (2017). "Extensive Amazonian-aged fluvial channels on Mars: Evaluating the role of Lyot crater in their formation". Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (11): 5336–5344. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..44.5336W. doi:10.1002/2017GL073821. S2CID 27711077.

- ^ "Hot Rocks Led to Relatively Recent Water-Carved Valleys on Mars - SpaceRef". 14 June 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Stones, Wind, and Ice: A Guide to Martian Impact Craters".

- ^ a b Hugh H. Kieffer (1992). Mars. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1257-7. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.uahirise.org/epo/nuggets/expanded-secondary.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Viola, D., et al. 2014. "Expanded Craters in Arcadia Planitia: Evidence for >20 MYR Old Subsurface Ice". Eighth International Conference on Mars (2014). 1022pdf.

- ^ Sharp, R. 1973. "Mars Fretted and chaotic terrains". J. Geophys. Res.: 78. 4073–4083

- ^ http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2000/pdf/1053.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b Plaut, J. et al. 2008. "Radar Evidence for Ice in Lobate Debris Aprons in the Mid-Northern Latitudes of Mars". Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIX. 2290.pdf

- ^ Plaut, J.; Safaeinili, A.; Holt, J.; Phillips, R.; Head, J.; Seu, R.; Putzig, N.; Frigeri, A. (2009). "Radar evidence for ice in lobate debris aprons in the midnorthern latitudes of Mars". Geophys. Res. Lett. 36 (2): n/a. Bibcode:2009GeoRL..36.2203P. doi:10.1029/2008GL036379. S2CID 17530607.

- ^ "European Space Agency". www.esa.int.

- ^ http://news.discovery.com/space/mars-ice-sheet-climate.html [dead link]

- ^ Madeleine, J. et al. 2007. "Exploring the northern mid-latitude glaciation with a general circulation model". In: Seventh International Conference on Mars. Abstract 3096.

- ^ "HiRISE | Glacier? (ESP_018857_2225)". www.uahirise.org.

- ^ "HiRISE | Fretted Terrain Valley Traverse (PSP_009719_2230)".

- ^ "HiRISE | Jumbled Flow Patterns (PSP_006278_2225)". hirise.lpl.arizona.edu.

- ^ a b Hecht, M (2002). "Metastability of water on Mars". Icarus. 156 (2): 373–386. Bibcode:2002Icar..156..373H. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6794.

- ^ a b Mustard, J.; et al. (2001). "Evidence for recent climate change on Mars from the identification of youthful near-surface ground ice". Nature. 412 (6845): 411–414. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..411M. doi:10.1038/35086515. PMID 11473309. S2CID 4409161.

- ^ Pollack, J.; Colburn, D.; Flaser, F.; Kahn, R.; Carson, C.; Pidek, D. (1979). "Properties and effects of dust suspended in the martian atmosphere". J. Geophys. Res. 84: 2929–2945. Bibcode:1979JGR....84.2929P. doi:10.1029/jb084ib06p02929.

- ^ Touma, J.; Wisdom, J. (1993). "The Chaotic Obliquity of Mars". Science. 259 (5099): 1294–1297. Bibcode:1993Sci...259.1294T. doi:10.1126/science.259.5099.1294. PMID 17732249. S2CID 42933021.

- ^ a b Laskar, J.; Correia, A.; Gastineau, M.; Joutel, F.; Levrard, B.; Robutel, P. (2004). "Long term evolution and chaotic diffusion of the insolation quantities of Mars" (PDF). Icarus. 170 (2): 343–364. Bibcode:2004Icar..170..343L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.04.005. S2CID 33657806.

- ^ Levy, J.; Head, J.; Marchant, D.; Kowalewski, D. (2008). "Identification of sublimation-type thermal contraction crack polygons at the proposed NASA Phoenix landing site: Implications for substrate properties and climate-driven morphological evolution". Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (4): L04202. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..35.4202L. doi:10.1029/2007GL032813.

- ^ Levy, J.; Head, J.; Marchant, D. (2009a). "Thermal contraction crack polygons on Mars: Classification, distribution, and climate implications from HiRISE observations". J. Geophys. Res. 114 (E1): E01007. Bibcode:2009JGRE..114.1007L. doi:10.1029/2008JE003273.

- ^ Hauber, E., D. Reiss, M. Ulrich, F. Preusker, F. Trauthan, M. Zanetti, H. Hiesinger, R. Jaumann, L. Johansson, A. Johnsson, S. Van Gaselt, M. Olvmo. 2011. Landscape evolution in Martian mid-latitude regions: insights from analogous periglacial landforms in Svalbard. In: Balme, M., A. Bargery, C. Gallagher, S. Guta (eds). Martian Geomorphology. Geological Society, London. Special Publications: 356. 111–131

- ^ Mellon, M.; Jakosky, B. (1995). "The distribution and behavior of Martian ground ice during past and present epochs". J. Geophys. Res. 100 (E6): 11781–11799. Bibcode:1995JGR...10011781M. doi:10.1029/95je01027. S2CID 129106439.

- ^ Schorghofer, N (2007). "Dynamics of ice ages on Mars". Nature. 449 (7159): 192–194. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..192S. doi:10.1038/nature06082. PMID 17851518. S2CID 4415456.

- ^ Madeleine, J., F. Forget, J. Head, B. Levrard, F. Montmessin. 2007. "Exploring the northern mid-latitude glaciation with a general circulation model". In: Seventh International Conference on Mars. Abstract 3096.

- ^ "HiRISE | Layered Mantling Deposits in the Northern Mid-Latitudes (ESP_048897_2125)". www.uahirise.org.

- ^ Carr, M (2001). "Mars Global Surveyor observations of martian fretted terrain". J. Geophys. Res. 106 (E10): 23571–23593. Bibcode:2001JGR...10623571C. doi:10.1029/2000je001316. S2CID 129715420.

- ^ Morgenstern, A., et al. 2007

- ^ a b Baker, D., J. Head. 2015. Extensive Middle Amazonian mantling of debris aprons and plains in Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars: Implication for the record of mid-latitude glaciation. Icarus: 260, 269–288.

- ^ Mangold, N (2003). "Geomorphic analysis of lobate debris aprons on Mars at Mars Orbiter Camera scale: Evidence for ice sublimation initiated by fractures". J. Geophys. Res. 108 (E4): 8021. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.8021M. doi:10.1029/2002je001885.

- ^ Levy, J. et al. 2009. Concentric

- ^ "Bright Chunks at Phoenix Lander's Mars Site Must Have Been Ice" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine – Official NASA press release (19.06.2008)

- ^ a b "NASA - Bright Chunks at Phoenix Lander's Mars Site Must Have Been Ice". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-09-01.

- ^ Byrne, S.; et al. (2009). "Distribution of Mid-Latitude Ground Ice on Mars from New Impact Craters". Science. 325 (5948): 1674–1676. Bibcode:2009Sci...325.1674B. doi:10.1126/science.1175307. PMID 19779195. S2CID 10657508.

- ^ Smith, P.; et al. (2009). "H2O at the Phoenix Landing Site". Science. 325 (5936): 58–61. Bibcode:2009Sci...325...58S. doi:10.1126/science.1172339. PMID 19574383. S2CID 206519214.

- ^ Head, J. et al. 2003.

- ^ Madeleine, et al. 2014.

- ^ Schon; et al. (2009). "A recent ice age on Mars: Evidence for climate oscillations from regional layering in mid-latitude mantling deposits". Geophys. Res. Lett. 36 (15): L15202. Bibcode:2009GeoRL..3615202S. doi:10.1029/2009GL038554.

- ^ R.J. Soare et al. 2013. Sub-kilometre (intra-crater) mounds in Utopia Planitia, Mars: character, occurrence and possible formation hypotheses, Icarus, 225, 982–991.

- ^ Morgenstern, A,, et al. 2007. Deposition and degradation of a volatile-rich layer in Utopia Planitia and implications for climate history on Mars. Journal of Geophysical Research Planets. Volume 112. IssueE6

- ^ Carr, M. 2001. "Mars Global Surveyor observations of martian fretted terrain". J. Geophys. Res. 106, 23571-23593.

- ^ Baker, D., J. Head. 2015. "Extensive Middle Amazonian mantling of debris aprons and plains in Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars: Implication for the record of mid-latitude glaciation". Icarus: 260, 269-288

- ^ Blanc, E., et al. 2024. ORIGIN OF WIDESPREAD LAYERED DEPOSITS ASSOCIATED WITH MARTIAN DEBRIS COVERED GLACIERS. 55th LPSC (2024). 1466.pdf

- ^ Irwin III, R. et al. 2005. "An intense terminal epoch of widespread fluvial activity on early Mars: 2. Increased runoff and paleolake development." Journal of Geophysical Research: 10. E12S15

- ^ "HiRISE | Fretted Terrain Valley Traverse (PSP_009719_2230)". Hirise.lpl.arizona.edu. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ Smellie, J., B. Edwards. 2016. Glaciovolcanism on Earth and Mars. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Levy, J.; et al. (2017). "Candidate volcanic and impact-induced ice depressions on Mars". Icarus. 285: 185–194. Bibcode:2017Icar..285..185L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.10.021.

- ^ University of Texas at Austin. "A funnel on Mars could be a place to look for life". ScienceDaily. 10 November 2016. .

- ^ "Refubium - Search" (PDF).

- ^ Kostama, V.-P.; Kreslavsky, Head (2006). "Recent high-latitude icy mantle in the northern plains of Mars: Characteristics and ages of emplacement". Geophys. Res. Lett. 33 (11): L11201. Bibcode:2006GeoRL..3311201K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.553.1127. doi:10.1029/2006GL025946. S2CID 17229252.

- ^ Malin, M.; Edgett, K. (2001). "Mars Global Surveyor Mars Orbiter Camera: Interplanetary cruise through primary mission". J. Geophys. Res. 106 (E10): 23429–23540. Bibcode:2001JGR...10623429M. doi:10.1029/2000je001455. S2CID 129376333.

- ^ Milliken, R.; et al. (2003). "Viscous flow features on the surface of Mars: Observations from high-resolution Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) images". J. Geophys. Res. 108 (E6): E6. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.5057M. doi:10.1029/2002JE002005. S2CID 12628857.

- ^ Mangold, N (2005). "High latitude patterned grounds on Mars: Classification, distribution and climatic control". Icarus. 174 (2): 336–359. Bibcode:2005Icar..174..336M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.07.030.

- ^ Kreslavsky, M.; Head, J. (2000). "Kilometer-scale roughness on Mars: Results from MOLA data analysis". J. Geophys. Res. 105 (E11): 26695–26712. Bibcode:2000JGR...10526695K. doi:10.1029/2000je001259.

- ^ Seibert, N.; Kargel, J. (2001). "Small-scale martian polygonal terrain: Implications or liquid surface water". Geophys. Res. Lett. 28 (5): 899–902. Bibcode:2001GeoRL..28..899S. doi:10.1029/2000gl012093.

- ^ Kreslavsky, M.A., Head, J.W., 2002. "High-latitude Recent Surface Mantle on Mars: New Results from MOLA and MOC". European Geophysical Society XXVII, Nice.

- ^ Head, J.W.; Mustard, J.F.; Kreslavsky, M.A.; Milliken, R.E.; Marchant, D.R. (2003). "Recent ice ages on Mars". Nature. 426 (6968): 797–802. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..797H. doi:10.1038/nature02114. PMID 14685228. S2CID 2355534.

- ^ "HiRISE | Dunes and Inverted Craters in Arabia Terra (ESP_016459_1830)". hirise.lpl.arizona.edu.

- ^ Michael H. Carr (2006). The surface of Mars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87201-0. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Sand Dunes - Phenomena of the Wind - DesertUSA". www.desertusa.com.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Curiosity Rover Report (Dec. 15, 2015): First Visit to Martian Dunes – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Flowing Sands of Mars". 9 May 2012.

- ^ Namowitz, S., Stone, D. 1975. Earth science the world we live in. American Book Company. New York.

- ^ "NASA Rover's Sand-Dune Studies Yield Surprise". Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^ Parker, T. J.; Gorsline, D. S.; Saunders, R. S.; Pieri, D. C.; Schneeberger, D. M. (1993). "Coastal geomorphology of the Martian northern plains". J. Geophys. Res. 98 (E6): 11061–11078. Bibcode:1993JGR....9811061P. doi:10.1029/93je00618.

- ^ Fairén, A. G.; et al. (2003). "Episodic flood inundations of the northern plains of Mars" (PDF). Icarus. 165 (1): 53–67. Bibcode:2003Icar..165...53F. doi:10.1016/s0019-1035(03)00144-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ Head, J. W.; et al. (1999). "Possible ancient oceans on Mars: Evidence from Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter data". Science. 286 (5447): 2134–2137. Bibcode:1999Sci...286.2134H. doi:10.1126/science.286.5447.2134. PMID 10591640.

- ^ Parker, T. J., Saunders, R. S. & Schneeberger, D. M. Transitional morphology in west Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars: Implications for modification of the lowland/upland boundary" Icarus 1989; 82, 111–145

- ^ Carr, M. H.; Head, J. W. (2003). "Oceans on Mars: An assessment of the observational evidence and possible fate". J. Geophys. Res. 108 (E5): 5042. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.5042C. doi:10.1029/2002JE001963.

- ^ Kreslavsky, M. A.; Head, J. W. (2002). "Fate of outflow channel effluent in the northern lowlands of Mars: The Vastitas Borealis Formation as a sublimation residue from frozen ponded bodies of water". J. Geophys. Res. 107 (E12): 5121. Bibcode:2002JGRE..107.5121K. doi:10.1029/2001JE001831.

- ^ Clifford, S. M. & Parker, T. J. The evolution of the martian hydrosphere: Implications for the fate of a primordial ocean and the current state of the northern plains" Icarus 2001; 154, 40–79

- ^ "Ancient Tsunami Evidence on Mars Reveals Life Potential" (Press release). May 20, 2016.

- ^ Rodriguez, J.; et al. (2016). "Tsunami waves extensively resurfaced the shorelines of an early Martian ocean". Scientific Reports. 6: 25106. Bibcode:2016NatSR...625106R. doi:10.1038/srep25106. PMC 4872529. PMID 27196957.

- ^ Rodriguez, J. Alexis P.; Fairén, Alberto G.; Tanaka, Kenneth L.; Zarroca, Mario; Linares, Rogelio; Platz, Thomas; Komatsu, Goro; Miyamoto, Hideaki; Kargel, Jeffrey S.; Yan, Jianguo; Gulick, Virginia; Higuchi, Kana; Baker, Victor R.; Glines, Natalie (2016). "Tsunami waves extensively resurfaced the shorelines of an early Martian ocean". Scientific Reports. 6: 25106. Bibcode:2016NatSR...625106R. doi:10.1038/srep25106. PMC 4872529. PMID 27196957.

- ^ Cornell University. "Ancient tsunami evidence on Mars reveals life potential." ScienceDaily, 19 May 2016. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/05/160519101756.htm.

- ^ Harrington, J.D.; Webster, Guy (July 10, 2014). "RELEASE 14-191 – NASA Spacecraft Observes Further Evidence of Dry Ice Gullies on Mars". NASA. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ^ Baker, D., L. Carter. 2018. Formation of Impact Crater Landforms within Glacial Deposits on Mars. 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2083). 1589.pdf

- ^ Baker, David M.H.; Carter, Lynn M. (2019). "Probing supraglacial debris on Mars 2: Crater morphology". Icarus. 319: 264–280. Bibcode:2019Icar..319..264B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.09.009. S2CID 126156734.