Radar signal characteristics

A radar system uses a radio-frequency electromagnetic signal reflected from a target to determine information about that target. In any radar system, the signal transmitted and received will exhibit many of the characteristics described below.

In the time domain

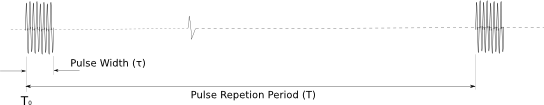

The diagram below shows the characteristics of the transmitted signal in the time domain. Note that in this and in all the diagrams within this article, the x axis is exaggerated to make the explanation clearer.

Carrier

The carrier is an RF signal, typically of microwave frequencies, which is usually (but not always) modulated to allow the system to capture the required data. In simple ranging radars, the carrier will be pulse modulated and in continuous wave systems, such as Doppler radar, modulation may not be required. Most systems use pulse modulation, with or without other supplementary modulating signals. Note that with pulse modulation, the carrier is simply switched on and off in sync with the pulses; the modulating waveform does not actually exist in the transmitted signal and the envelope of the pulse waveform is extracted from the demodulated carrier in the receiver. Although obvious when described, this point is often missed when pulse transmissions are first studied, leading to misunderstandings about the nature of the signal.

Pulse width

The pulse width () (or pulse duration) of the transmitted signal is the time, typically in microseconds, each pulse lasts. If the pulse is not a perfect square wave, the time is typically measured between the 50% power levels of the rising and falling edges of the pulse.

The pulse width must be long enough to ensure that the radar emits sufficient energy so that the reflected pulse is detectable by its receiver. The amount of energy that can be delivered to a distant target is the product of two things; the peak output power of the transmitter, and the duration of the transmission. Therefore, pulse width constrains the maximum detection range of a target.

Pulse width also constrains the range discrimination, that is the capacity of the radar to distinguish between two targets that are close together. At any range, with similar azimuth and elevation angles and as viewed by a radar with an unmodulated pulse, the range resolution is approximately equal in distance to half of the pulse duration times the speed of light (approximately 300 meters per microsecond).

Pulse width also determines the radar's dead zone at close ranges. While the radar transmitter is active, the receiver input is blanked to avoid the amplifiers being swamped (saturated) or, (more likely), damaged. A simple calculation reveals that a radar echo will take approximately 10.8 μs to return from a target 1 statute mile away (counting from the leading edge of the transmitter pulse (T0), (sometimes known as transmitter main bang)). For convenience, these figures may also be expressed as 1 nautical mile in 12.4 μs or 1 kilometre in 6.7 μs. (For simplicity, all further discussion will use metric figures.) If the radar pulse width is 1 μs, then there can be no detection of targets closer than about 150 m, because the receiver is blanked.

All this means that the designer cannot simply increase the pulse width to get greater range without having an impact on other performance factors. As with everything else in a radar system, compromises have to be made to a radar system's design to provide the optimal performance for its role.

Pulse repetition frequency (PRF)

In order to build up a discernible echo, most radar systems emit pulses continuously and the repetition rate of these pulses is determined by the role of the system. An echo from a target will therefore be 'painted' on the display or integrated within the signal processor every time a new pulse is transmitted, reinforcing the return and making detection easier. The higher the PRF that is used, then the more the target is painted. However, with the higher PRF the range that the radar can "see" is reduced. Radar designers try to use the highest PRF possible commensurate with the other factors that constrain it, as described below.

There are two other facets related to PRF that the designer must weigh very carefully; the beamwidth characteristics of the antenna, and the required periodicity with which the radar must sweep the field of view. A radar with a 1° horizontal beamwidth that sweeps the entire 360° horizon every 2 seconds with a PRF of 1080 Hz will radiate 6 pulses over each 1-degree arc. If the receiver needs at least 12 reflected pulses of similar amplitudes to achieve an acceptable probability of detection, then there are three choices for the designer: double the PRF, halve the sweep speed, or double the beamwidth. In reality, all three choices are used, to varying extents; radar design is all about compromises between conflicting pressures.

Staggered PRF

Staggered PRF is a transmission process where the time between interrogations from radar changes slightly, in a patterned and readily-discernible repeating manner. The change of repetition frequency allows the radar, on a pulse-to-pulse basis, to differentiate between returns from its own transmissions and returns from other radar systems with the same PRF and a similar radio frequency. Consider a radar with a constant interval between pulses; target reflections appear at a relatively constant range related to the flight-time of the pulse. In today's very crowded radio spectrum, there may be many other pulses detected by the receiver, either directly from the transmitter or as reflections from elsewhere. Because their apparent "distance" is defined by measuring their time relative to the last pulse transmitted by "our" radar, these "jamming" pulses could appear at any apparent distance. When the PRF of the "jamming" radar is very similar to "our" radar, those apparent distances may be very slow-changing, just like real targets. By using stagger, a radar designer can force the "jamming" to jump around erratically in apparent range, inhibiting integration and reducing or even suppressing its impact on true target detection.

Without staggered PRF, any pulses originating from another radar on the same radio frequency might appear stable in time and could be mistaken for reflections from the radar's own transmission. With staggered PRF the radar's own targets appear stable in range in relation to the transmit pulse, whilst the 'jamming' echoes may move around in apparent range (uncorrelated), causing them to be rejected by the receiver. Staggered PRF is only one of several similar techniques used for this, including jittered PRF (where the pulse timing is varied in a less-predictable manner), pulse-frequency modulation, and several other similar techniques whose principal purpose is to reduce the probability of unintentional synchronicity. These techniques are in widespread use in marine safety and navigation radars, by far the most numerous radars on planet Earth today.

Clutter

Clutter refers to radio frequency (RF) echoes returned from targets which are uninteresting to the radar operators. Such targets include natural objects such as ground, sea, precipitation (such as rain, snow or hail), sand storms, animals (especially birds), atmospheric turbulence, and other atmospheric effects, such as ionosphere reflections, meteor trails, and three body scatter spike. Clutter may also be returned from man-made objects such as buildings and, intentionally, by radar countermeasures such as chaff.

Some clutter may also be caused by a long radar waveguide between the radar transceiver and the antenna. In a typical plan position indicator (PPI) radar with a rotating antenna, this will usually be seen as a "sun" or "sunburst" in the centre of the display as the receiver responds to echoes from dust particles and misguided RF in the waveguide. Adjusting the timing between when the transmitter sends a pulse and when the receiver stage is enabled will generally reduce the sunburst without affecting the accuracy of the range, since most sunburst is caused by a diffused transmit pulse reflected before it leaves the antenna. Clutter is considered a passive interference source, since it only appears in response to radar signals sent by the radar.

Clutter is detected and neutralized in several ways. Clutter tends to appear static between radar scans; on subsequent scan echoes, desirable targets will appear to move, and all stationary echoes can be eliminated. Sea clutter can be reduced by using horizontal polarization, while rain is reduced with circular polarization (note that meteorological radars wish for the opposite effect, and therefore use linear polarization to detect precipitation). Other methods attempt to increase the signal-to-clutter ratio.

Clutter moves with the wind or is stationary. Two common strategies to improve measure or performance in a clutter environment are:

- Moving target indication, which integrates successive pulses and

- Doppler processing, which uses filters to separate clutter from desirable signals.

The most effective clutter reduction technique is pulse-Doppler radar with Look-down/shoot-down capability. Doppler separates clutter from aircraft and spacecraft using a frequency spectrum, so individual signals can be separated from multiple reflectors located in the same volume using velocity differences. This requires a coherent transmitter. Another technique uses a moving target indication that subtracts the receive signal from two successive pulses using phase to reduce signals from slow moving objects. This can be adapted for systems that lack a coherent transmitter, such as time-domain pulse-amplitude radar.

Constant False Alarm Rate, a form of Automatic Gain Control (AGC), is a method that relies on clutter returns far outnumbering echoes from targets of interest. The receiver's gain is automatically adjusted to maintain a constant level of overall visible clutter. While this does not help detect targets masked by stronger surrounding clutter, it does help to distinguish strong target sources. In the past, radar AGC was electronically controlled and affected the gain of the entire radar receiver. As radars evolved, AGC became computer-software controlled and affected the gain with greater granularity in specific detection cells.

Clutter may also originate from multipath echoes from valid targets caused by ground reflection, atmospheric ducting or ionospheric reflection/refraction (e.g., Anomalous propagation). This clutter type is especially bothersome since it appears to move and behave like other normal (point) targets of interest. In a typical scenario, an aircraft echo is reflected from the ground below, appearing to the receiver as an identical target below the correct one. The radar may try to unify the targets, reporting the target at an incorrect height, or eliminating it on the basis of jitter or a physical impossibility. Terrain bounce jamming exploits this response by amplifying the radar signal and directing it downward.[1] These problems can be overcome by incorporating a ground map of the radar's surroundings and eliminating all echoes which appear to originate below ground or above a certain height. Monopulse can be improved by altering the elevation algorithm used at low elevation. In newer air traffic control radar equipment, algorithms are used to identify the false targets by comparing the current pulse returns to those adjacent, as well as calculating return improbabilities.

Sensitivity time control (STC)

STC is used to avoid saturation of the receiver from close in ground clutter by adjusting the attenuation of the receiver as a function of distance. More attenuation is applied to returns close in and is reduced as the range increases.

Unambiguous range

- Single PRF

In simple systems, echoes from targets must be detected and processed before the next transmitter pulse is generated if range ambiguity is to be avoided. Range ambiguity occurs when the time taken for an echo to return from a target is greater than the pulse repetition period (T); if the interval between transmitted pulses is 1000 microseconds, and the return-time of a pulse from a distant target is 1200 microseconds, the apparent distance of the target is only 200 microseconds. In sum, these 'second echoes' appear on the display to be targets closer than they really are.

Consider the following example : if the radar antenna is located at around 15 m above sea level, then the distance to the horizon is pretty close, (perhaps 15 km). Ground targets further than this range cannot be detected, so the PRF can be quite high; a radar with a PRF of 7.5 kHz will return ambiguous echoes from targets at about 20 km, or over the horizon. If however, the PRF was doubled to 15 kHz, then the ambiguous range is reduced to 10 km and targets beyond this range would only appear on the display after the transmitter has emitted another pulse. A target at 12 km would appear to be 2 km away, although the strength of the echo might be much lower than that from a genuine target at 2 km.

The maximum non ambiguous range varies inversely with PRF and is given by:

where c is the speed of light. If a longer unambiguous range is required with this simple system, then lower PRFs are required and it was quite common for early search radars to have PRFs as low as a few hundred Hz, giving an unambiguous range out to well in excess of 150 km. However, lower PRFs introduce other problems, including poorer target painting and velocity ambiguity in Pulse-Doppler systems (see below).

- Multiple PRF

Modern radars, especially air-to-air combat radars in military aircraft, may use PRFs in the tens-to-hundreds of kilohertz and stagger the interval between pulses to allow the correct range to be determined. With this form of staggered PRF, a packet of pulses is transmitted with a fixed interval between each pulse, and then another packet is transmitted with a slightly different interval. Target reflections appear at different ranges for each packet; these differences are accumulated and then simple arithmetical techniques may be applied to determine true range. Such radars may use repetitive patterns of packets, or more adaptable packets that respond to apparent target behaviors. Regardless, radars that employ the technique are universally coherent, with a very stable radio frequency, and the pulse packets may also be used to make measurements of the Doppler shift (a velocity-dependent modification of the apparent radio frequency), especially when the PRFs are in the hundreds-of-kilohertz range. Radars exploiting Doppler effects in this manner typically determine relative velocity first, from the Doppler effect, and then use other techniques to derive target distance.

- Maximum Unambiguous Range

At its most simplistic, MUR (Maximum Unambiguous Range) for a Pulse Stagger sequence may be calculated using the TSP (Total Sequence Period). TSP is defined as the total time it takes for the Pulsed pattern to repeat. This can be found by the addition of all the elements in the stagger sequence. The formula is derived from the speed of light and the length of the sequence [citation needed]:

where c is the speed of light, usually in metres per microsecond, and TSP is the addition of all the positions of the stagger sequence, usually in microseconds. However, in a stagger sequence, some intervals may be repeated several times; when this occurs, it is more appropriate to consider TSP as the addition of all the unique intervals in the sequence.

Also, it is worth remembering that there may be vast differences between the MUR and the maximum range (the range beyond which reflections will probably be too weak to be detected), and that the maximum instrumented range may be much shorter than either of these. A civil marine radar, for instance, may have user-selectable maximum instrumented display ranges of 72, or 96 or rarely 120 nautical miles, in accordance with international law, but maximum unambiguous ranges of over 40,000 nautical miles and maximum detection ranges of perhaps 150 nautical miles. When such huge disparities are noted, it reveals that the primary purpose of staggered PRF is to reduce "jamming", rather than to increase unambiguous range capabilities.

In the frequency domain

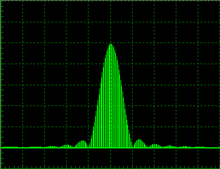

Pure CW radars appear as a single line on a Spectrum analyser display and when modulated with other sinusoidal signals, the spectrum differs little from that obtained with standard analogue modulation schemes used in communications systems, such as Frequency Modulation and consist of the carrier plus a relatively small number of sidebands. When the radar signal is modulated with a pulse train as shown above, the spectrum becomes much more complicated and far more difficult to visualise.

Basic Fourier analysis shows that any repetitive complex signal consists of a number of harmonically related sine waves. The radar pulse train is a form of square wave, the pure form of which consists of the fundamental plus all of the odd harmonics. The exact composition of the pulse train will depend on the pulse width and PRF, but mathematical analysis can be used to calculate all of the frequencies in the spectrum. When the pulse train is used to modulate a radar carrier, the typical spectrum shown on the left will be obtained.

Examination of this spectral response shows that it contains two basic structures. The coarse structure; (the peaks or 'lobes' in the diagram on the left) and the Fine Structure which contains the individual frequency components as shown below. The envelope of the lobes in the coarse structure is given by: .

Note that the pulse width () determines the lobe spacing. Smaller pulse widths result in wider lobes and therefore greater bandwidth.

Examination of the spectral response in finer detail, as shown on the right, shows that the Fine Structure contains individual lines or spot frequencies. The formula for the fine structure is given by and since the period of the PRF (T) appears at the bottom of the fine spectrum equation, there will be fewer lines if higher PRFs are used. These facts affect the decisions made by radar designers when considering the trade-offs that need to be made when trying to overcome the ambiguities that affect radar signals.

Pulse profiling

If the rise and fall times of the modulation pulses are zero, (e.g. the pulse edges are infinitely sharp), then the sidebands will be as shown in the spectral diagrams above. The bandwidth consumed by this transmission can be huge and the total power transmitted is distributed over many hundreds of spectral lines. This is a potential source of interference with any other device and frequency-dependent imperfections in the transmit chain mean that some of this power never arrives at the antenna. In reality of course, it is impossible to achieve such sharp edges, so in practical systems the sidebands contain far fewer lines than a perfect system. If the bandwidth can be limited to include relatively few sidebands, by rolling off the pulse edges intentionally, an efficient system can be realised with the minimum of potential for interference with nearby equipment. However, the trade-off of this is that slow edges make range resolution poor. Early radars limited the bandwidth through filtration in the transmit chain, e.g. the waveguide, scanner etc., but performance could be sporadic with unwanted signals breaking through at remote frequencies and the edges of the recovered pulse being indeterminate. Further examination of the basic Radar Spectrum shown above shows that the information in the various lobes of the Coarse Spectrum is identical to that contained in the main lobe, so limiting the transmit and receive bandwidth to that extent provides significant benefits in terms of efficiency and noise reduction.

Recent advances in signal processing techniques have made the use of pulse profiling or shaping more common. By shaping the pulse envelope before it is applied to the transmitting device, say to a cosine law or a trapezoid, the bandwidth can be limited at source, with less reliance on filtering. When this technique is combined with pulse compression, then a good compromise between efficiency, performance and range resolution can be realised. The diagram on the left shows the effect on the spectrum if a trapezoid pulse profile is adopted. It can be seen that the energy in the sidebands is significantly reduced compared to the main lobe and the amplitude of the main lobe is increased.

Similarly, the use of a cosine pulse profile has an even more marked effect, with the amplitude of the sidelobes practically becoming negligible. The main lobe is again increased in amplitude and the sidelobes correspondingly reduced, giving a significant improvement in performance.

There are many other profiles that can be adopted to optimise the performance of the system, but cosine and trapezoid profiles generally provide a good compromise between efficiency and resolution and so tend to be used most frequently.

Unambiguous velocity

This is an issue only with a particular type of system; the pulse-Doppler radar, which uses the Doppler effect to resolve velocity from the apparent change in frequency caused by targets that have net radial velocities compared to the radar device. Examination of the spectrum generated by a pulsed transmitter, shown above, reveals that each of the sidebands, (both coarse and fine), will be subject to the Doppler effect, another good reason to limit bandwidth and spectral complexity by pulse profiling.

Consider the positive shift caused by the closing target in the diagram which has been highly simplified for clarity. It can be seen that as the relative velocity increases, a point will be reached where the spectral lines that constitute the echoes are hidden or aliased by the next sideband of the modulated carrier. Transmission of multiple pulse-packets with different PRF-values, e.g. staggered PRFs, will resolve this ambiguity, since each new PRF value will result in a new sideband position, revealing the velocity to the receiver. The maximum unambiguous target velocity is given by:

Typical system parameters

Taking all of the above characteristics into account means that certain constraints are placed on the radar designer. For example, a system with a 3 GHz carrier frequency and a pulse width of 1 μs will have a carrier period of approximately 333 ps. Each transmitted pulse will contain about 3000 carrier cycles and the velocity and range ambiguity values for such a system would be:

| PRF | Velocity Ambiguity | Range Ambiguity |

|---|---|---|

| Low (2 kHz) | 50 m/s | 75 km |

| Medium (12 kHz) | 300 m/s | 12.5 km |

| High (200 kHz) | 5000 m/s | 750 m |

See also

- Aliasing - the reason for ambiguous velocity estimates

- Continuous-wave radar (non-pulsed, pure doppler processing)

- Weather radar (pulsed with doppler processing)

References

- ^ Strasser, Nancy C. "Investigation of Terrain Bounce Electronic Countermeasure". DTIC. Archived from the original on November 30, 2012.

- Modern Radar Systems by Hamish Meikle (ISBN 0-86341-172-X)

- Advanced Radar Techniques and Systems edited by Gaspare Galati (ISBN 1-58053-294-2)